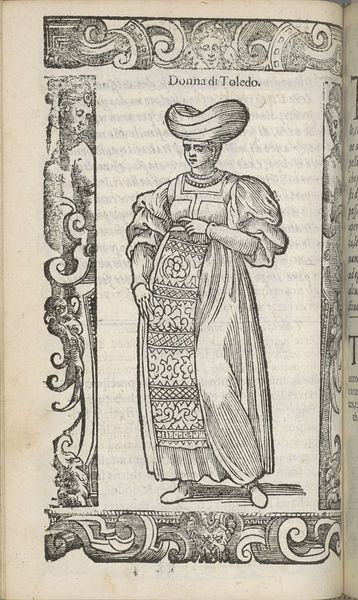

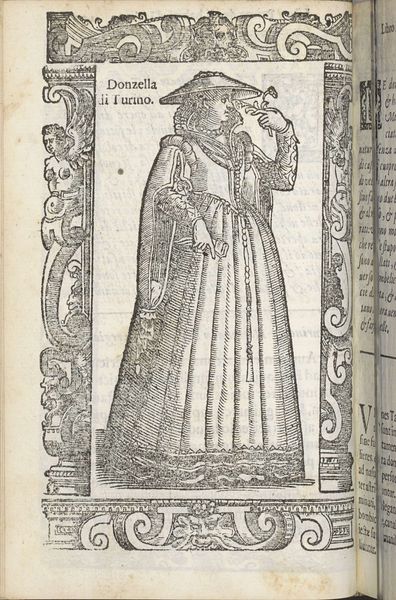

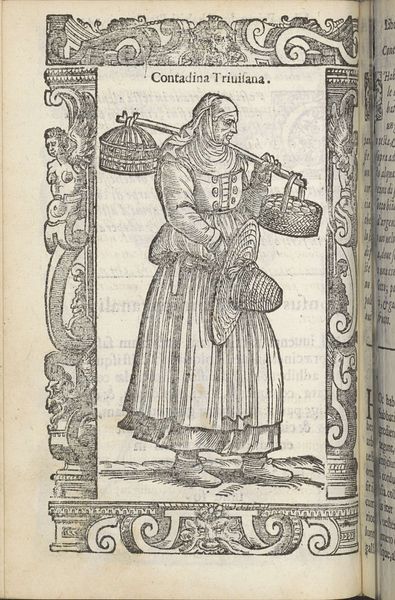

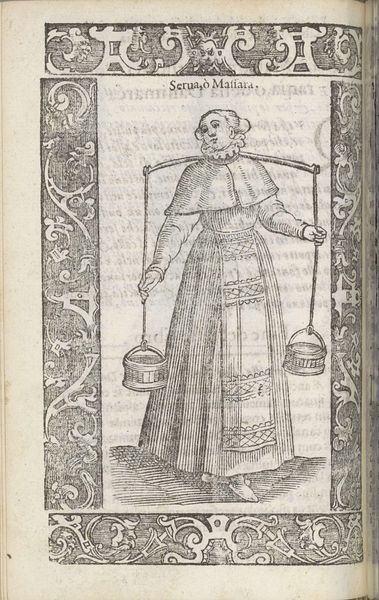

drawing, print, ink, woodcut

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

medieval

#

narrative-art

#

pen drawing

# print

#

figuration

#

ink

#

woodcut

#

line

#

northern-renaissance

Dimensions: height 167 mm, width 125 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

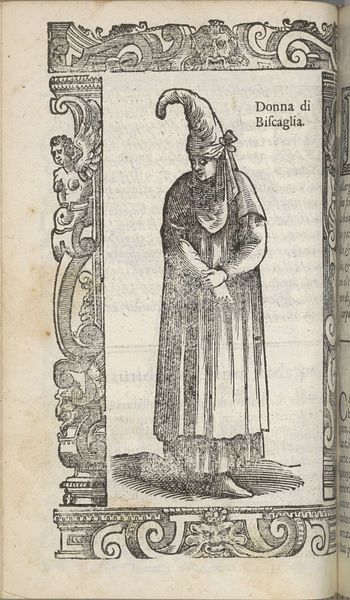

Editor: Here we have Christoph Krieger's "Volksvrouw uit Biskaje," from 1598, a print rendered in ink. It's a simple portrait of a woman with her spindle. It almost feels like an early form of documentation. What strikes you about it? Curator: The key is the mode of production itself: the woodcut, the ink. This wasn't about some airy, divine inspiration. It's labor, pure and simple. Think of the skill and time invested in carving that block. Editor: It looks quite precise! The level of detail in her clothing is remarkable for the medium. Curator: Exactly. And consider what she's doing: spinning. This image isn't just a depiction, it's about representing a material process. Cloth production shaped economies! How does this relate to gender roles, you think? Editor: Well, it’s clearly defining this woman by her labour. Spinning was very much tied to the feminine role. So is the artist commenting on that, or reinforcing it? Curator: Perhaps both. By depicting her labor so directly, the artist acknowledges its importance. Yet, by labeling her merely as a "Volksvrouw", a woman of the folk, and highlighting this typical act, does he reduce her identity to it? The context in which it's consumed also changes its value. This print may have served as part of an inventory of 'types' – and what implications does the assembly-line logic of printing have? Editor: I see what you mean! It forces you to consider how everyday labor gets represented, and the power dynamics embedded within that representation. Curator: Indeed. Thinking materially like this, examining process and function and circulation, transforms how we appreciate it. Editor: Absolutely! I’ll definitely think about art this way from now on, breaking it down in the making and considering how meaning is tied into production and reception.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.