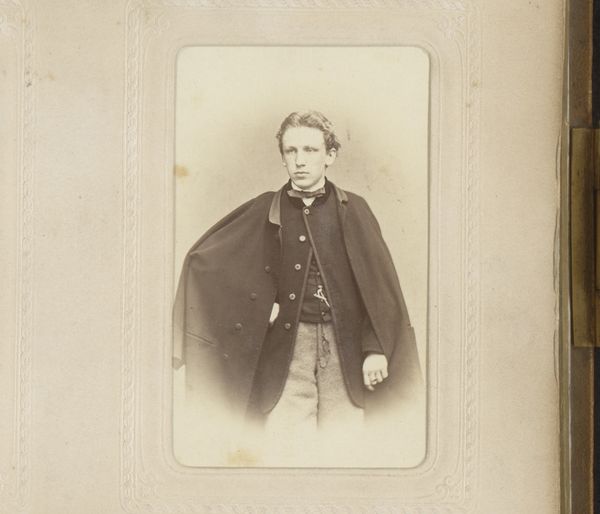

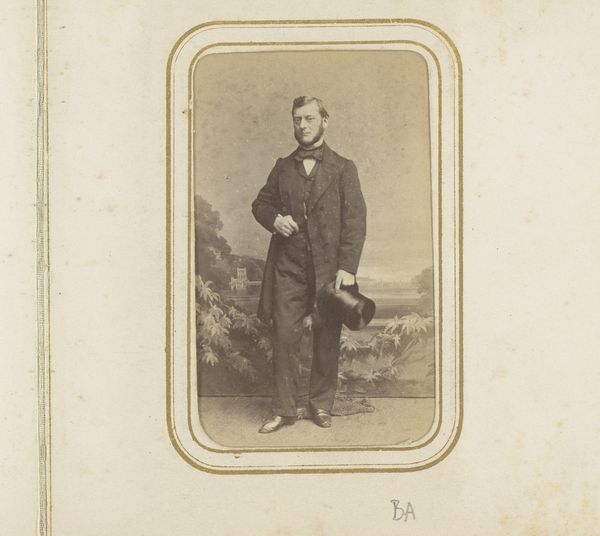

daguerreotype, photography

#

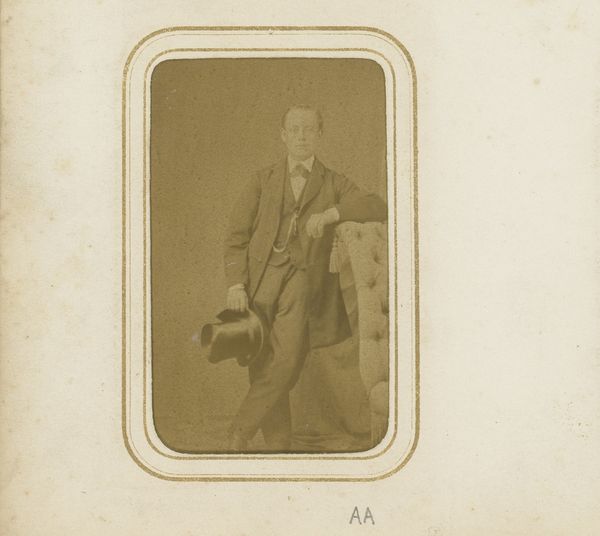

portrait

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

19th century

#

realism

Dimensions: height 83 mm, width 51 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this is Louis Wegner’s "Portret van een jongeman, staand bij een stoel," made sometime between 1857 and 1864. It's a daguerreotype, so it's an early photograph. The detail is fascinating, even if the lighting makes it feel a little somber. What's your take on this piece? Curator: Immediately, I’m drawn to the materiality. This daguerreotype, an image painstakingly coaxed onto a silvered copper plate, represents a specific moment in technological and social history. Look at the labor involved in its creation: the polishing, the sensitizing, the careful exposure. This isn't just a portrait, but a material record of 19th-century photographic practices. Editor: I see what you mean. It makes me think about access, too. Who would have been able to afford a portrait like this back then? Curator: Exactly. Think about the social context. Photography at this time was costly, largely reserved for the bourgeoisie. The young man's suit, the studio setting - they all point towards a certain social status and an investment in self-representation only afforded to a select few. Note the details, each painstakingly rendered through careful use of materials. Editor: The chair, though, feels almost propped like a generic object...like stage dressing. It kind of throws me off, if I'm honest. Curator: That tension is crucial. The chair, the backdrop - these are manufactured elements, staged to create an illusion of refined interiority. The entire image can be interpreted as a careful construct. It's not simply about capturing reality, but about crafting a carefully controlled representation of social aspiration and manufactured class identity through available materials. Editor: So, by analyzing the materials and the process, we are examining the economic realities of representation itself. Curator: Precisely. Wegner’s portrait isn’t just a face; it’s a document reflecting material and social hierarchies. Analyzing it through this lens illuminates the complex interplay between art, labor, and consumption in the 19th century. Editor: Wow, that’s given me a totally new perspective on something I would have considered “just” a portrait. Curator: Indeed. Sometimes the object's power rests within the framework that enabled its genesis and influenced the choices available.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.