Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

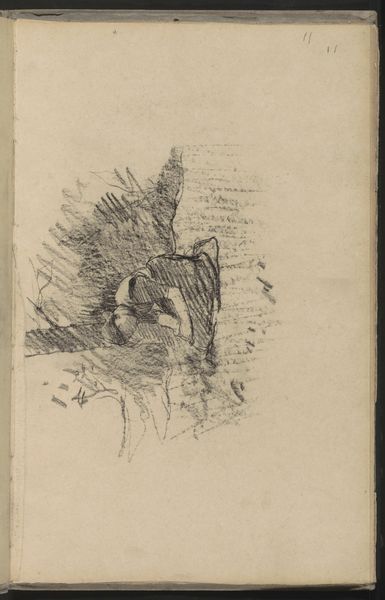

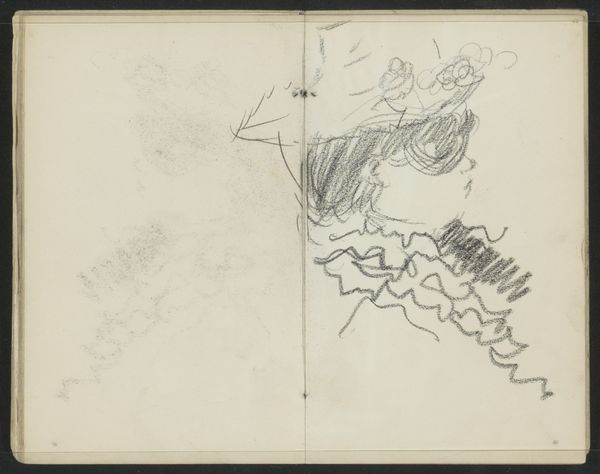

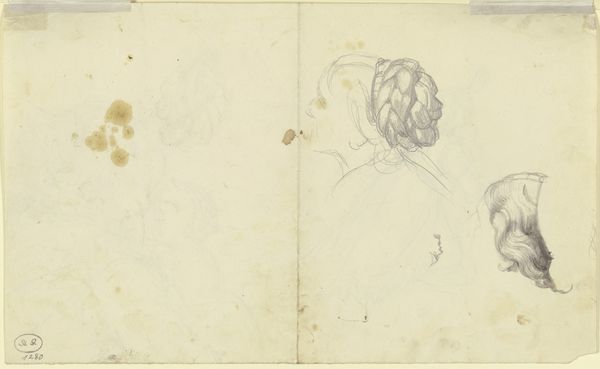

Curator: This piece, held here at the Rijksmuseum, is entitled "Vrouwenhoofd met hoed, in profiel," or "Woman's Head with Hat, in Profile," rendered by Isaac Israels between 1887 and 1934. It’s done with coloured pencils on paper. Editor: There's a haunting fragility to this work. The hurried, almost ghost-like lines, combined with the muted palette, suggest a fleeting impression, like a memory fading at the edges. I'm immediately curious about who she was, this woman shrouded in suggestive form. Curator: Well, Israels was certainly part of the Dutch Impressionist movement, moving away from strict academic portrayals, engaging instead with the reality of the subject and emphasizing how the sitter affected society. So the very sketchiness you observe can be seen as intentional, capturing a transient moment in time. Editor: Right, and isn’t it fascinating that we see her "in profile"? We're given just a glimpse. It raises interesting questions about women in that era. Were their identities often partially obscured, seen only from certain angles, socially dictated perspectives? Was Israels deliberately playing with this restricted view? Curator: It could also be seen that the use of the sketchbook recalls the way the street became a kind of ‘studio’ during that period. Think about how the rapid urbanization changed not only what artists saw, but how they could portray their reality. A rapid, sketchy form allowed him to represent these new impressions. Editor: That's a great point. Urbanization fundamentally altered social interactions. Consider this woman's social class as well—her hat likely signifies status, respectability, a carefully constructed identity within an emerging modern world. Israels' impressionistic rendering invites us to decode that very identity. How was the artist participating in or critiquing such constructions of gender and class through his style? Curator: His work generally reflects the social changes that were sweeping across Europe and beyond, in both subject matter and approach. It's part of a move that brought about entirely new subjectivities in the context of modernity. And to represent such things also changed the institutions of art and artmaking. Editor: Looking at the raw, vulnerable quality of those pencil lines, though, I think this goes beyond just observation or institutional change. I’m particularly touched by the brown smudges along the lower part, where you can still see the figure. To me, it expresses an emotive intimacy, an effort to intimately engage with a lived reality behind social surfaces, something shared between artist and model. Curator: Ultimately, “Vrouwenhoofd met hoed, in profiel” becomes a potent intersection between historical context, social commentary, and deeply personal artistic expression. Editor: It really makes us question the transient nature of existence and representation, both then and now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.