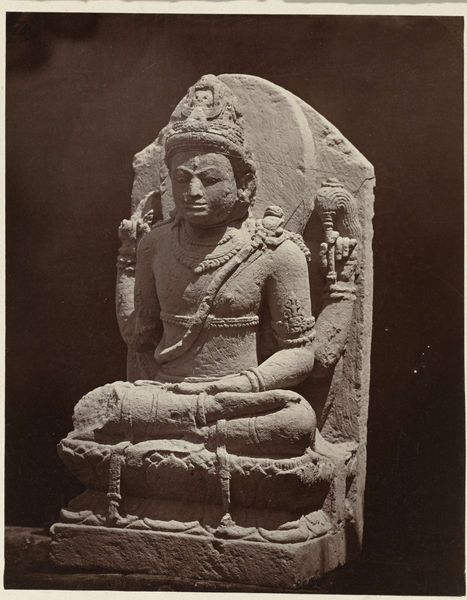

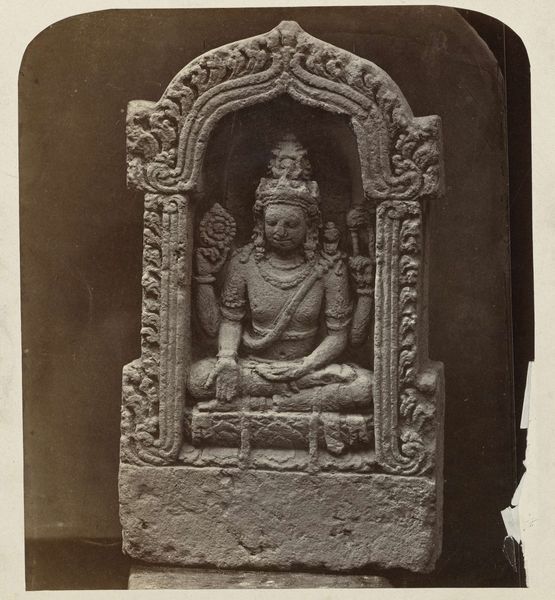

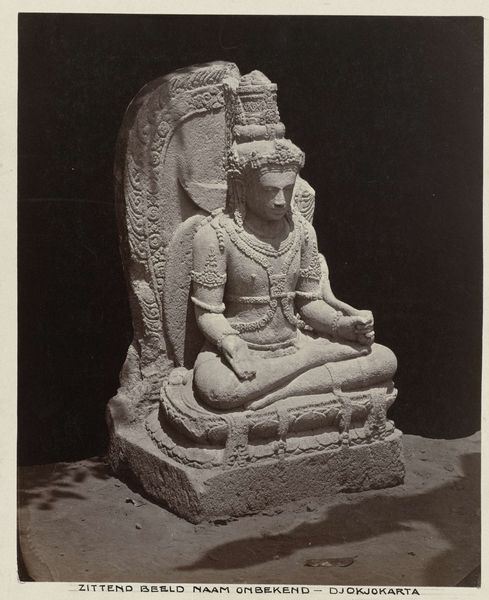

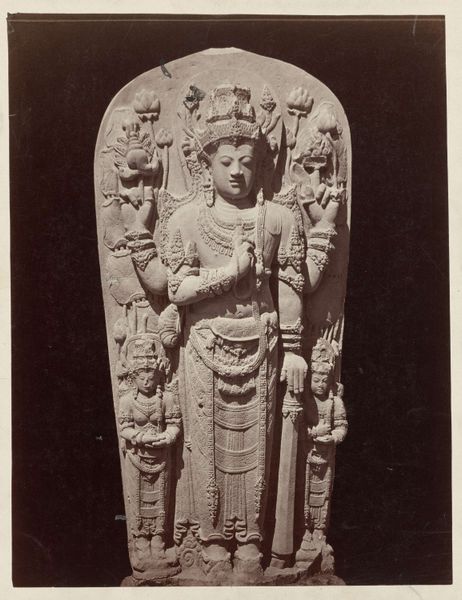

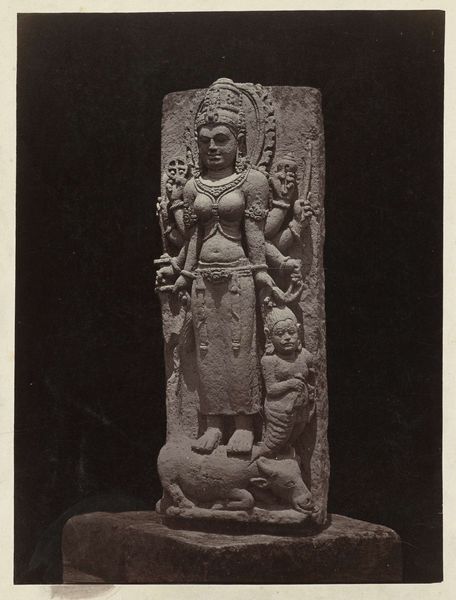

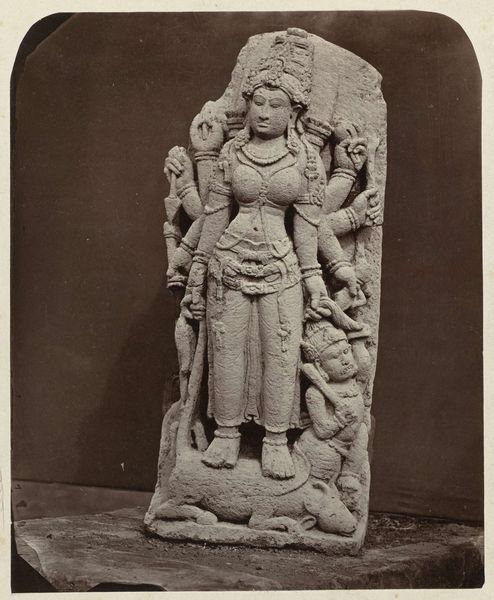

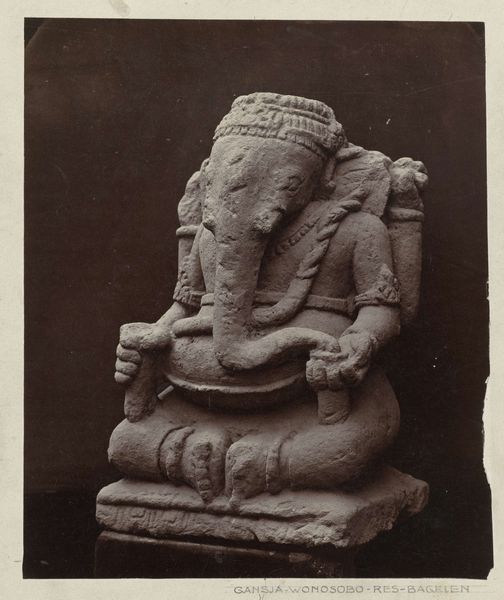

Four-armed Shiva decorating the entrance way to the residedncy of the assistent-resident of Wonosobo (provenance Dieng Plateau) Wonosobo, Wonosobo district, Central Java province, 10the century. 1864

0:00

0:00

carving, metal, sculpture

#

portrait

#

carving

#

metal

#

sculpture

#

asian-art

#

figuration

#

form

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

sculpture

#

history-painting

Dimensions: height 340 mm, width 290 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

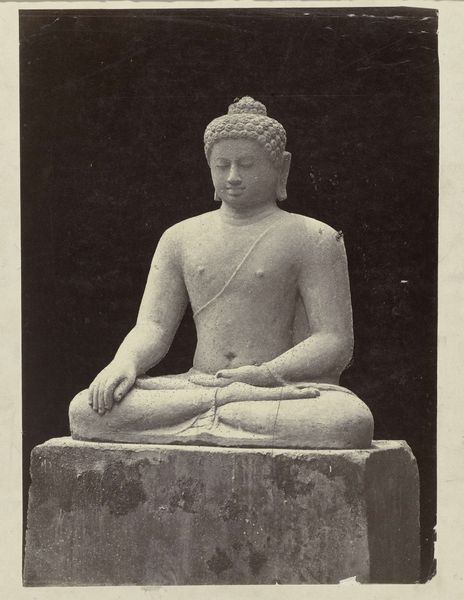

Editor: This is a photograph from 1864 by Isidore Kinsbergen, depicting a tenth-century sculpture of a four-armed Shiva. It's from the Dieng Plateau in Central Java. What strikes me is how serene the figure seems, even though it’s a fragmented ruin. What do you make of it? Curator: This image invites us to consider the politics of representation and preservation, doesn’t it? A photograph of a sculpture removed from its original context, presented to a Western audience in the colonial era. How does this displacement impact our understanding of Shiva and Javanese culture? Editor: I hadn't thought about it like that. So, you're saying the photograph itself is part of the story, not just a neutral record? Curator: Precisely! Kinsbergen, a Dutch photographer working in the Dutch East Indies, was creating a visual archive shaped by colonial interests. This Shiva, likely venerated locally, becomes an object of study, categorized and displayed for Western consumption. Consider also the pose of Shiva – the meditative lotus position. Is this serenity or power? And how are those concepts themselves shaped by colonial narratives? Editor: It’s almost as if the act of photographing, collecting, and labeling changes the meaning. It's no longer just a religious icon; it's evidence of a conquered culture. Curator: Exactly. And the fragmentation adds another layer. The brokenness might symbolize loss, but it can also stand as a reminder of resilience. Did the photographer intend this effect? Or is our reading of the damage a commentary on a shared cultural vulnerability? Editor: Wow, it's a lot more complex than I initially thought. I’m beginning to understand how images from this time aren't simply neutral records but active participants in the power dynamics of the colonial era. Thank you. Curator: My pleasure. Remembering that history and the ways it shaped the image we see transforms the viewing experience entirely, wouldn’t you agree?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.