photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

garden

#

16_19th-century

#

landscape

#

photography

#

orientalism

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

19th century

Dimensions: height 212 mm, width 276 mm, height 469 mm, width 558 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

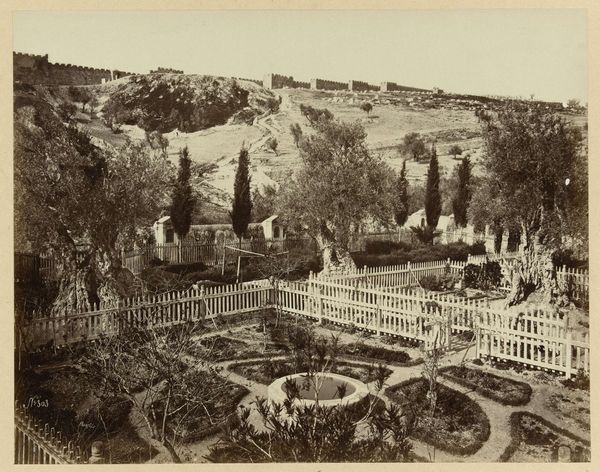

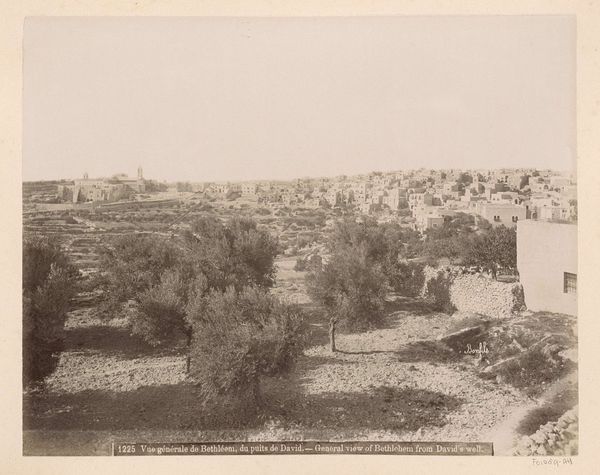

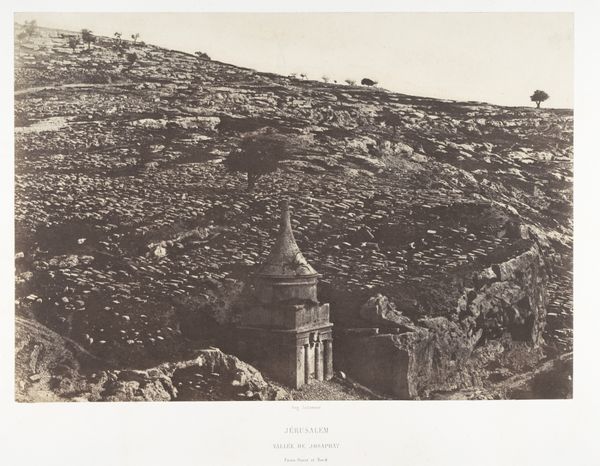

Curator: Fèlix Bonfils’ photograph, “Gezicht op de tuin van Getsemane, Jeruzalem,” dating from around 1867 to 1877, presents us with a gelatin silver print now housed at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It’s striking. The sepia tones lend a melancholic air, and the composition, with the figures almost hidden amongst the architectural and botanical elements, speaks of something both intimate and expansive. Curator: The “orientalist” style situates the artwork within the socio-political context of 19th-century Western attitudes toward the Middle East. How do you think that factors into how this image of Gethsemane might have been received? Editor: Absolutely. This photograph would have catered to a Western audience eager for exotic imagery, while also serving a documentary function. Notice the labor evident in creating this carefully ordered garden space in the desert landscape and, more pointedly, the gelatin-silver printing process and the mass reproduction it made possible. These photos reinforced particular power dynamics between the colonizing and colonized populations. Curator: That connection between the landscape, its representation, and imperial narratives is key. Bonfils was part of a larger phenomenon of photographers creating a visual record of the Middle East. But it is also crucial to recall this garden as a cultivated and constructed location through intense labor. Editor: Precisely. The photograph doesn’t just depict Gethsemane; it participates in constructing it as a space with political significance for a specific, viewing public. Consider the visual markers included by the photographer that reinforce notions of sacredness—and who these constructions of sacred places benefitted in that period. Curator: And, of course, how it exists now, reshaped by that history. The print's existence within the Rijksmuseum makes it an object that's been carefully selected and conserved—a reminder of how institutions shape art's narrative and access. Editor: Right. It started as documentation, functioned as art for collectors, and became a vehicle to understand political ideology! Well, looking closely reveals how complex even seemingly straightforward landscape imagery is, and just how enmeshed art is in the production of culture. Curator: Indeed. Bonfils’s photograph gives us layers of consideration around material culture and institutional forces at play during that time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.