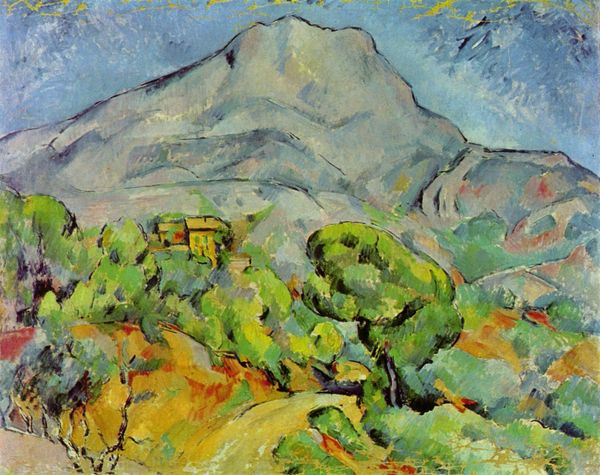

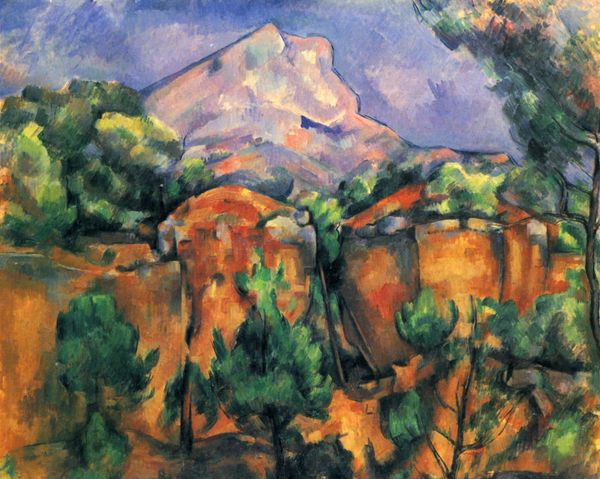

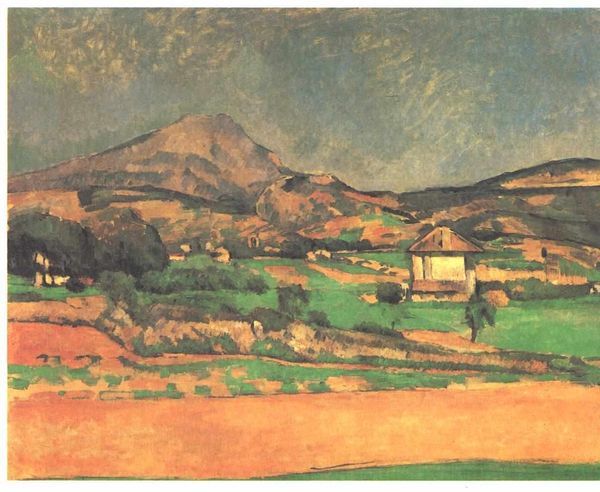

Copyright: Public domain

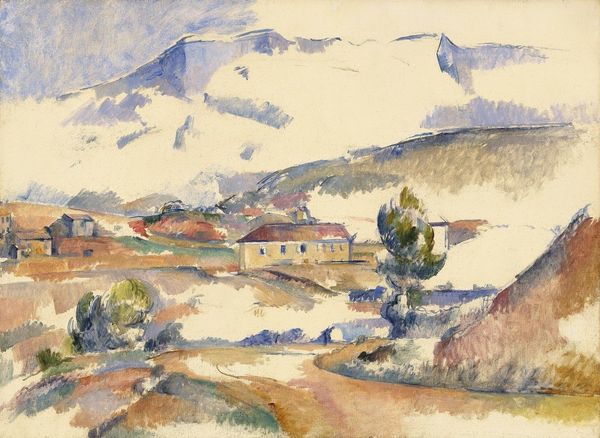

Editor: This is Paul Cézanne's "Mont Sainte-Victoire," painted in 1898, and rendered with oil on canvas. There’s such a dreamlike quality to it – like a hazy memory of a place. What historical contexts do you see at play in this piece? Curator: Cézanne's landscapes, including this one, are steeped in the complex socio-political history of late 19th-century France. Remember the shifts following the Franco-Prussian War and the rise of industrialization. He turned to the landscape of his native Provence, deliberately avoiding urban and academic themes embraced by the art establishment. How do you think that positioning affects its public reception? Editor: So, it's a rejection of the established order, a kind of turning inward? It feels like he's almost building the landscape from scratch with each brushstroke. Curator: Exactly! And consider how the Impressionists and early Post-Impressionists were initially rejected by the Salon, the main arbiter of artistic taste. Cézanne’s unique approach paved the way for future generations who challenged conventional modes of representation. Did his background in Aix influence the evolution of modern art? Editor: It’s incredible to think about. So a landscape, simply put, becomes a statement. The way art institutions now embrace Cézanne— displaying paintings such as these– it highlights how tastes and values change, especially when reflecting a specific view in space and time. Curator: Precisely. And it reminds us that what we consider “great art” is constantly being reshaped by socio-political forces, and whose perspectives hold authority to say so. A humble mountain transforms into a powerful symbol. Editor: It's really eye-opening to consider the history embedded within what I initially saw as a beautiful landscape. Thank you! Curator: My pleasure. Reflecting on such pieces illuminates the ongoing conversation about art's role in society and who gets to shape it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.