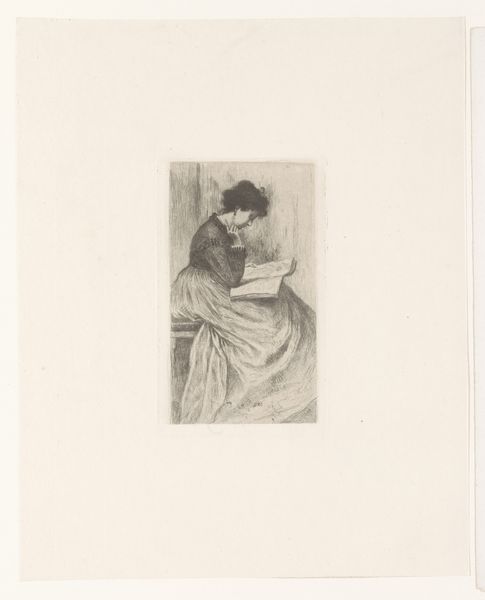

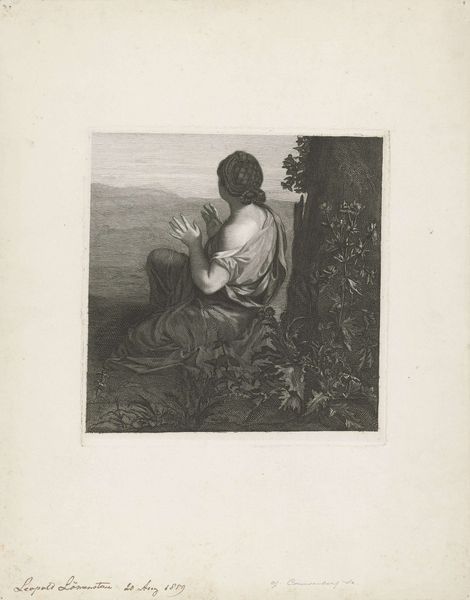

drawing, print, etching, paper

#

portrait

#

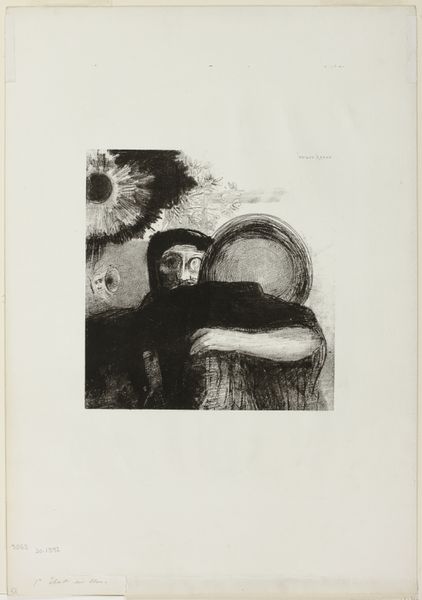

drawing

#

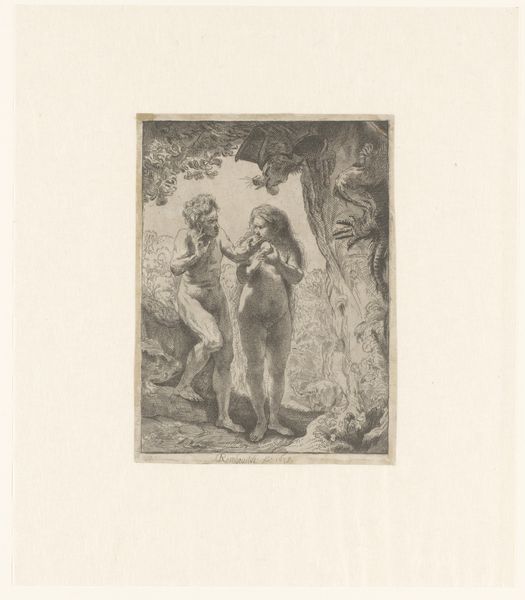

narrative-art

# print

#

etching

#

figuration

#

paper

#

symbolism

Dimensions: 496 × 336 mm (plate); 620 × 464 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

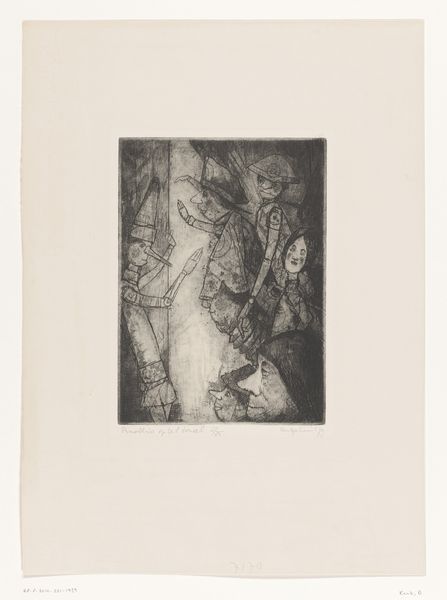

Editor: We're looking at "Dreams, plate three from A Life," an 1884 etching by Max Klinger, currently at the Art Institute of Chicago. It’s incredibly dark and unsettling; the woman in the foreground looks terrified, with shadowy figures looming behind her. What can you tell me about it? Curator: Klinger's series “A Life” provides insight into the social and psychological landscape of the late 19th century. Notice how the imagery leans heavily on symbolism and the subconscious, moving away from purely representational art. How might this piece reflect the societal anxieties of the time? Editor: It almost feels like a Freudian nightmare. Is Klinger trying to show us something about the repressed desires and anxieties of the Victorian era? Curator: Exactly. This was a time when the emerging middle class had increasing access to education, yet also faced the pressure of social expectations. Etchings and prints like this made art accessible beyond the elite, fostering a visual culture where complex themes could be debated more widely. Do you think this accessibility played a role in shaping the piece’s content or reception? Editor: Definitely. Printmaking made art a part of broader cultural conversations, but how would audiences at the time have received this? It's so dark. Curator: Precisely. Klinger's style would have challenged conventional tastes but, paradoxically, contributed to shaping new ones, thus prompting the debate on social norms, class divisions, and personal freedom. Editor: That’s a great point; thinking about the role of prints as accessible art really changes how I see it. Curator: It sheds light on how art wasn't just a reflection of society, but a tool that could mold perceptions and ignite social dialogue.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.