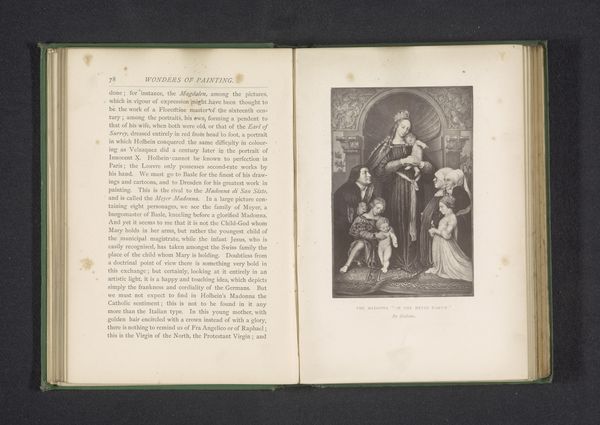

Fotoreproductie van een schilderij van Maria met Kind door Hans Holbein before 1864

0:00

0:00

print, photography

#

portrait

# print

#

11_renaissance

#

photography

#

northern-renaissance

Dimensions: height 141 mm, width 98 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

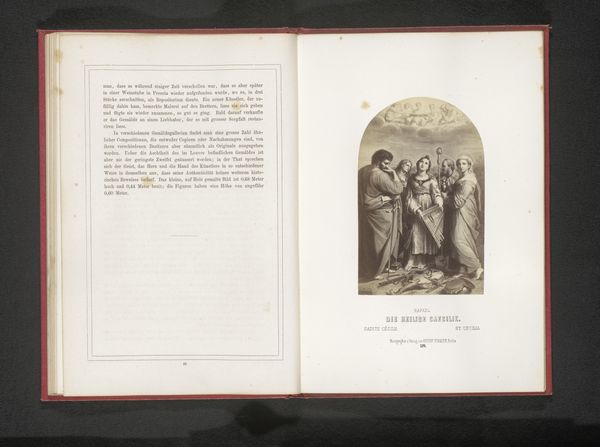

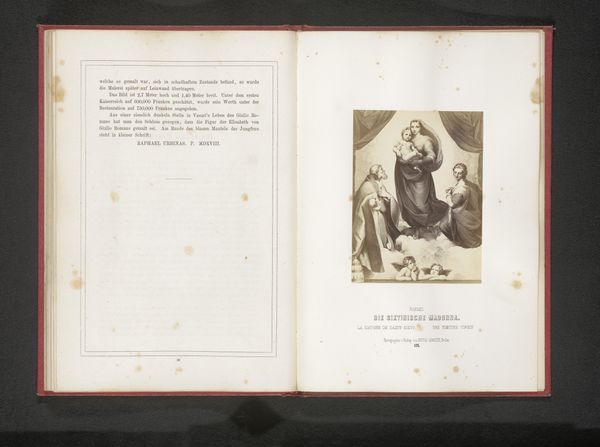

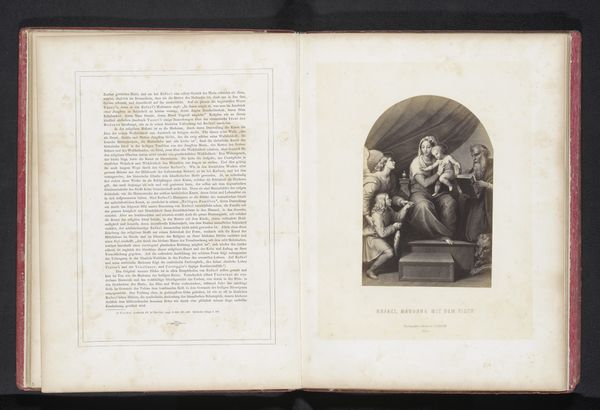

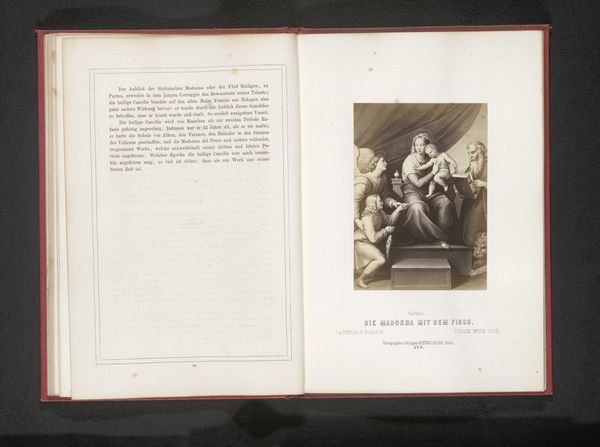

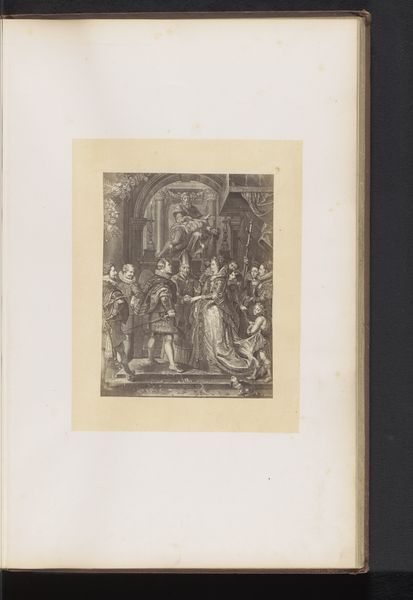

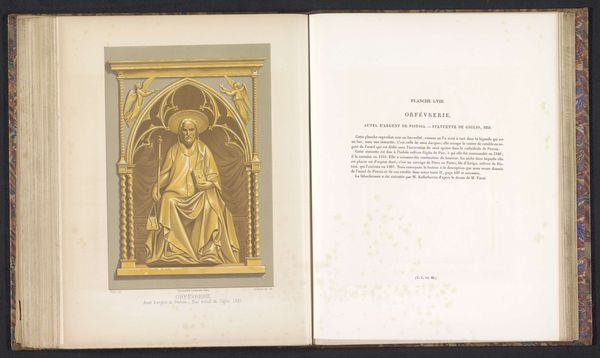

Curator: This striking image before us is a photographic reproduction of a painting of the Virgin Mary and Child, likely by Hanns Hanfstaengl, and dating from before 1864. It exists within a print form, housed within an album. Editor: Immediately, the reproduction's monochrome tones create a somber mood. I’m drawn to the central figure, of course, but the encircling individuals evoke a claustrophobic atmosphere—a real sense of historical positioning. Curator: The interesting thing here is the transition from the original painted medium to photographic reproduction. Think about the materials involved: the chemicals, the photographic paper, the printing process itself. What does it mean to translate such a historically loaded image through a relatively new industrial medium? Editor: It underscores, I think, the changing relationship between art, technology, and audience. Consider how photography democratized access to images once reserved for the elite. But beyond mere access, it shifts power, offering opportunities for appropriation and re-interpretation by varied social groups. The virgin mother becomes reproducible, a symbolic gesture considering the changing familial structures within Europe. Curator: Absolutely. We also need to acknowledge Hanfstaengl’s position. He’s not just reproducing art; he’s participating in an emerging industry—a system of artistic reproduction that has profound consequences for artists’ labor. The role of the photographer here is as a technician and disseminator, embedded in a specific set of capitalist production methods. Editor: True. Furthermore, seeing Mary replicated for potential consumption sparks necessary feminist discourse about the representation of motherhood itself, a vital concept from theological art which served to encourage gendered and racial roles. By extension, one cannot ignore how notions of gender and class intertwine during this era. Who exactly had access to this reproduction, and for what ideological ends? Curator: So, through examining the material history of this photographic print—the processes involved in its making, and the social and economic context surrounding it—we uncover a broader network of power and representation. Editor: Right, stepping back, this reproduction embodies a nexus of socio-cultural narratives. Its monochromatic depiction and replicable form challenge our assumptions around notions of originality, questioning authorship itself in our modern, ever-changing world.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.