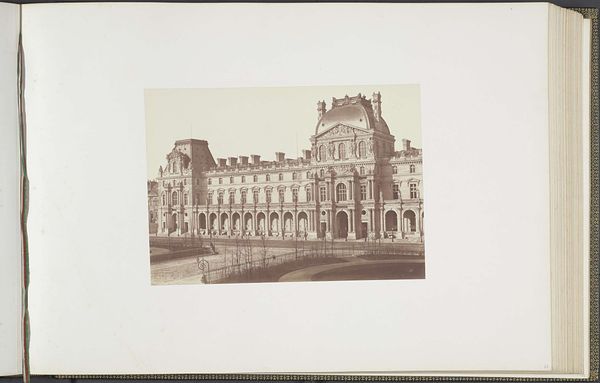

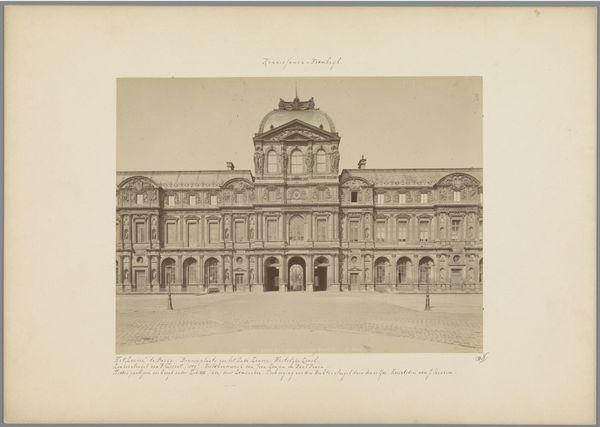

Cour Napoléon en het Pavillon Sully gezien vanaf de Turgot-vleugel 1857

0:00

0:00

edouardbaldus

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 382 mm, width 558 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: We’re looking at Edouard Baldus' photograph, "Cour Napoléon en het Pavillon Sully gezien vanaf de Turgot-vleugel," taken in 1857. It’s a gelatin silver print capturing a grand view of the Louvre. The imposing architecture and quiet courtyard give a strong sense of the monumentality. What historical narratives do you find embedded within this image? Curator: This image encapsulates the ambitions of Napoleon III, deeply invested in projecting imperial power through architecture and urban planning. Baldus was commissioned to document the "New Louvre" project, an expansion designed to visually and symbolically link Napoleon III's regime with past French glory. The very act of photographing the site – capturing a specific perspective, time of day, and absence of bustling crowds – serves a political purpose, constructing an image of order and grandeur that contrasts with the social realities of Paris at the time. Do you notice the absence of people? Editor: I do now. The emptiness does feel deliberate, almost staged. It makes the building feel more like a symbol than a space people actually used. Curator: Exactly. Consider how photography, then a relatively new medium, was being strategically employed by institutions and political powers. This image, meticulously crafted, presents an idealized vision of progress and imperial control, a calculated visual statement aimed at shaping public perception both then and now. We also should discuss romanticism as an aesthetic choice as well, where ruins are appreciated alongside idealized grandeur, speaking volumes about the time in which it was captured. Editor: So, it's less about pure documentation and more about constructing a specific historical narrative? I didn't realize how layered even a seemingly straightforward architectural photograph could be. Thanks for shedding some light on that. Curator: Precisely. Examining the socio-political context allows us to deconstruct the image and appreciate its complex role in shaping history and public memory. There’s so much more beneath the surface.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.