photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

medieval

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

realism

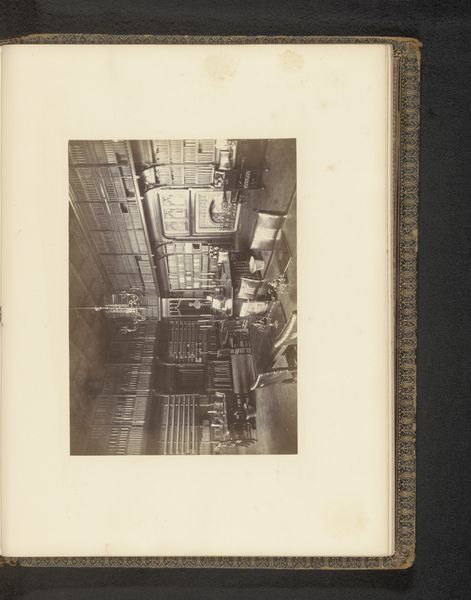

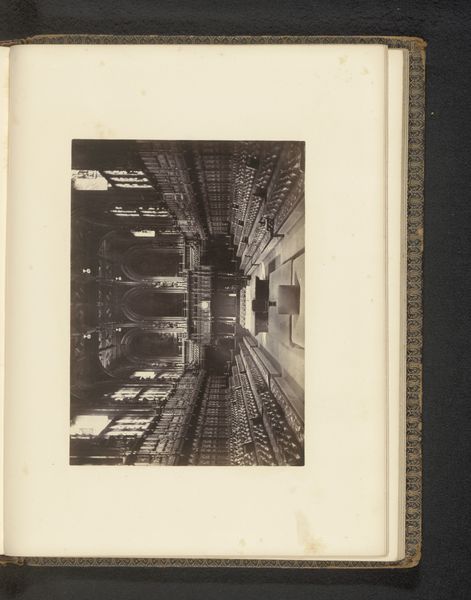

Dimensions: height 130 mm, width 186 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

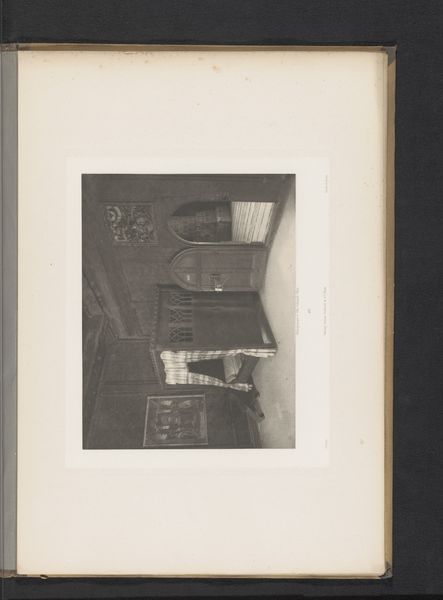

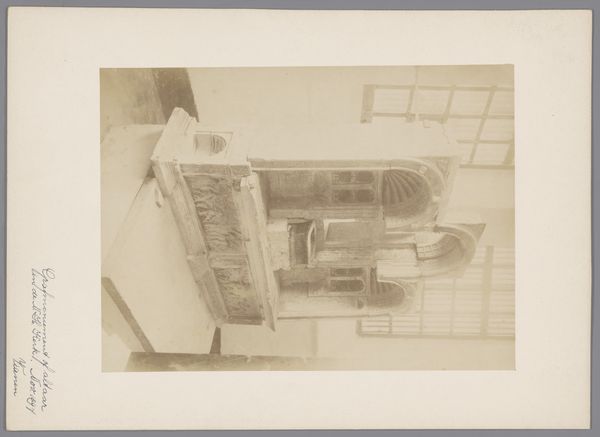

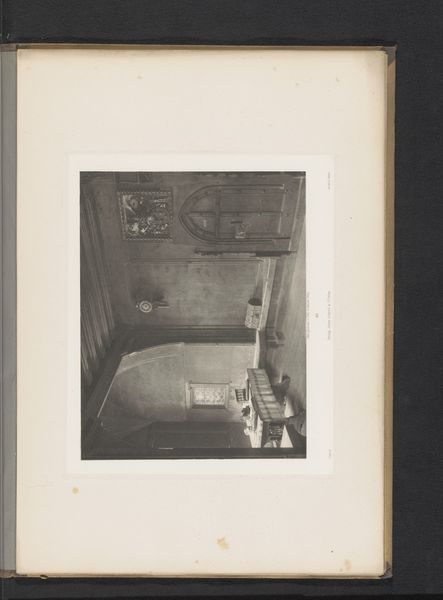

Curator: What a strikingly geometric composition. The angles pull your eye into what feels like an infinite vanishing point. Editor: It's a gelatin-silver print titled "Retabel te Westminster Abbey," and it seems to predate 1869, a testament to early photographic techniques capturing the medieval essence of the architecture. What really grabs me is imagining the conditions of production back then—the cumbersome equipment, the long exposures required, the specialized knowledge… This image really speaks to the labour involved. Curator: I see your point. However, what strikes me first is how the tonal range evokes the solemnity of the space, it's expertly rendered in shades of gray, achieving a visual harmony. The realism is incredible given the primitive photographic means of the time. Editor: "Realism," sure, but let’s not forget the photographer, likely John Harrington, exercised immense control over the materials and their presentation. The choice of albumen print emphasizes certain textural qualities, glosses over others. The materiality literally constructs our perception of this “real” space. Also consider the intended consumer – most likely upper class due to photographic cost and lack of access, an echo of medieval patronage networks for artisans. Curator: Absolutely, but isn’t it more than just a product of labor and economic stratification? The architecture itself becomes almost an abstract pattern through the lens, a dialogue between light and form. The geometry pushes beyond the simple depiction to ask what it means to capture and frame space. Editor: But that sense of “abstract pattern” comes from very real material processes! Think of the alchemical transformation within the darkroom, the delicate balance between chemicals, light, and the choices made regarding focus and aperture which affected the depth of field and ultimately the look. The material determines how the architecture becomes image. Curator: I grant your points, but I can’t help but feel the weight of architectural history—its grandeur diminished and preserved through geometry— speaks volumes outside of only the materials utilized and the processes employed. Editor: Indeed, the ability to preserve this grandeur does come directly through the utilization of new photographic processes of the time and we can ask ourselves how and for what purpose this preservation served within Victorian society. It seems a beautiful tension between image, architecture, materials, and production.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.