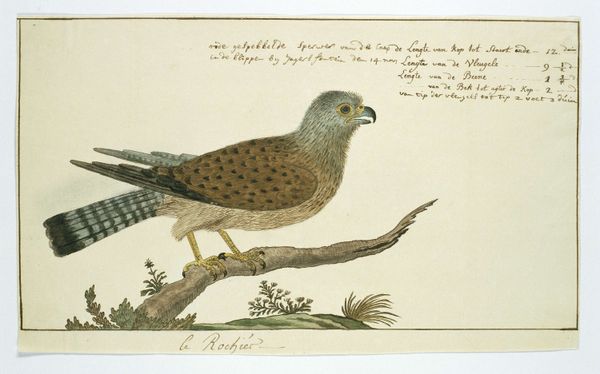

drawing, watercolor

#

portrait

#

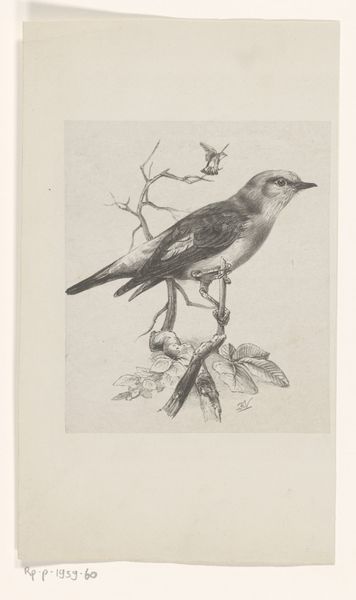

drawing

#

watercolor

#

watercolour illustration

#

naturalism

Dimensions: height 660 mm, width 480 mm, height 305 mm, width 220 mm, height mm, width mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let's consider this striking watercolor drawing, "Pycnonotus capensis (Cape bulbul)," attributed to Robert Jacob Gordon, likely created between 1777 and 1786. It’s a beautiful example of naturalistic illustration. Editor: My immediate thought is that the delicate lines create a sense of calm. It feels incredibly precise, but the almost monochromatic palette gives it a muted, subtle power. Curator: Absolutely. Given Gordon’s position as a military commander for the Dutch East India Company, these drawings are often read through the lens of colonialism and scientific exploration. How does understanding Gordon’s labor within that framework affect your view? Editor: It casts the piece in a different light. Suddenly, it's not just a bird, but a piece of data, a record, an element in the exploitation of natural resources. The artist's hand becomes part of a much larger, more problematic process. The materiality – the paper, the watercolors – they become tools of empire. Curator: Exactly. His exploration and cataloging also reflect broader issues of power and the representation of the "other." Consider, for instance, how the focus on detail, perhaps influenced by the Linnaean system of classification, impacted ideas about the natural world. Editor: And consider where those materials come from. Who made the paper? Who ground the pigments? This drawing isn't just Gordon's labor; it's the culmination of countless acts of production, probably exploiting local knowledge. The apparent delicacy of the work belies its violent context. Curator: Yes, and even the bulbul itself is imbricated within networks of exploitation through agricultural expansion and later development in Southern Africa. The seemingly benign image holds complex and unsettling layers. Editor: It makes you rethink what it means to look closely. What looks like careful observation is in fact a form of possession, through which nature is codified and consumed. Curator: So, beyond the naturalistic style, and with this intersectional understanding of the bird in historical context, how does the image speak to you now? Editor: It feels less innocent. The technique draws me in, but the larger context forces a critical assessment. It compels me to examine the ethics of representation and extraction – questions that still resonate strongly today. Curator: For me, recognizing these complexities enhances its impact. By acknowledging the drawing’s history, we can start meaningful dialogues about our own roles within ongoing systems of power and representation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.