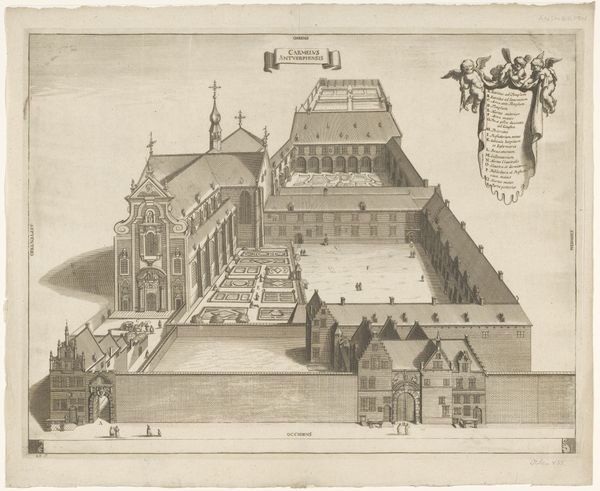

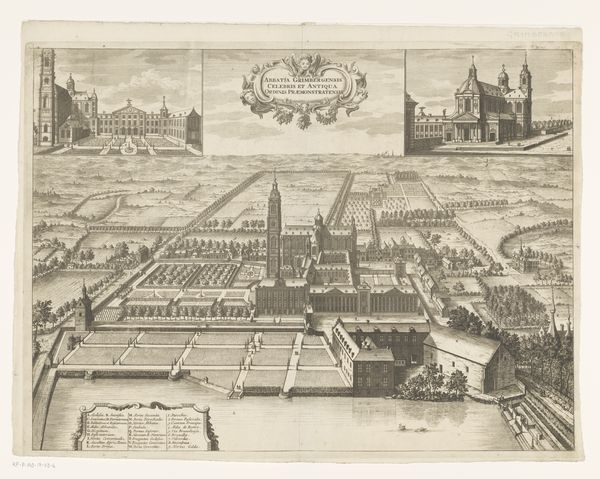

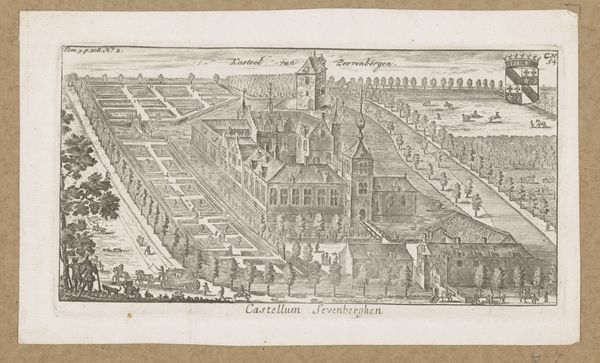

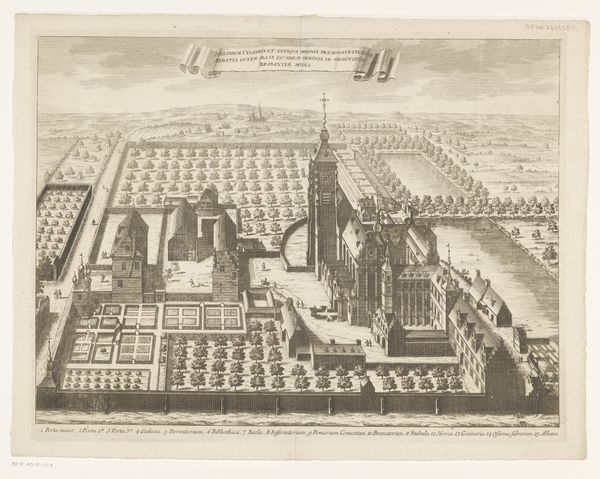

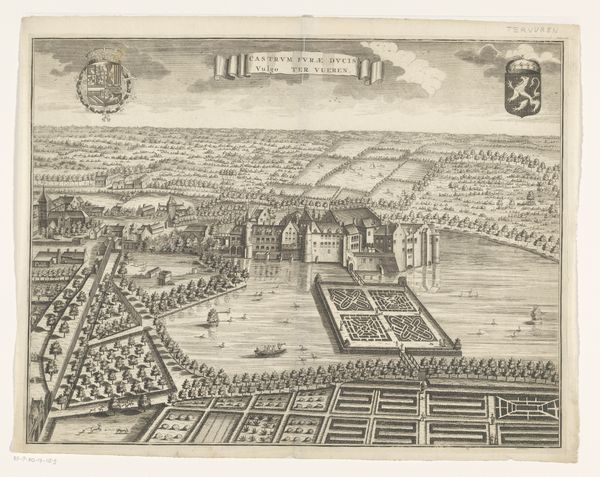

drawing, print, engraving

#

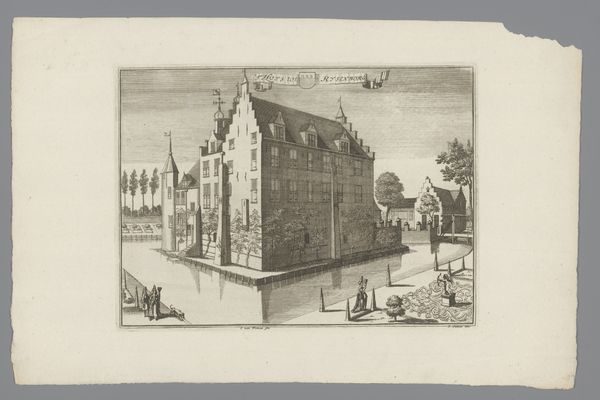

drawing

#

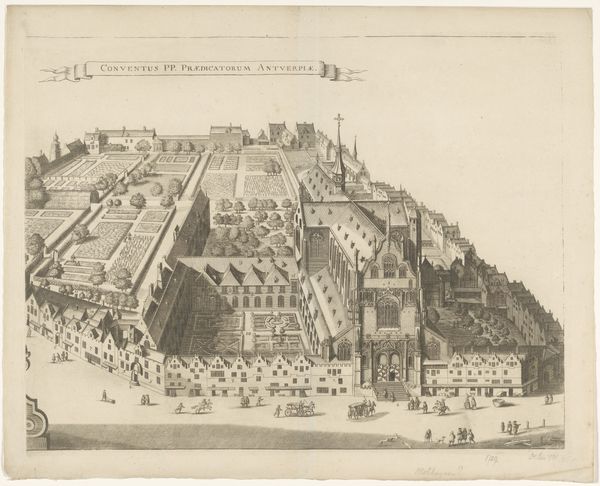

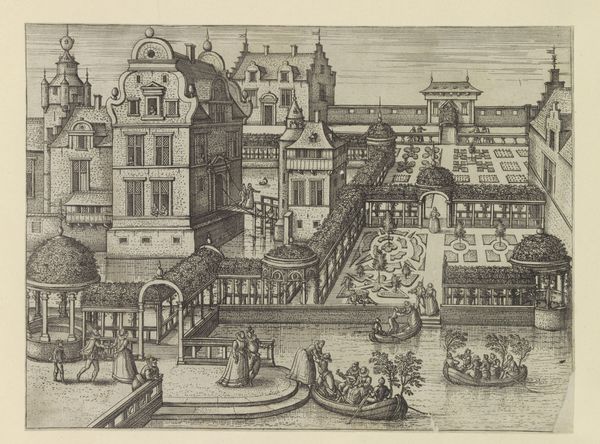

baroque

# print

#

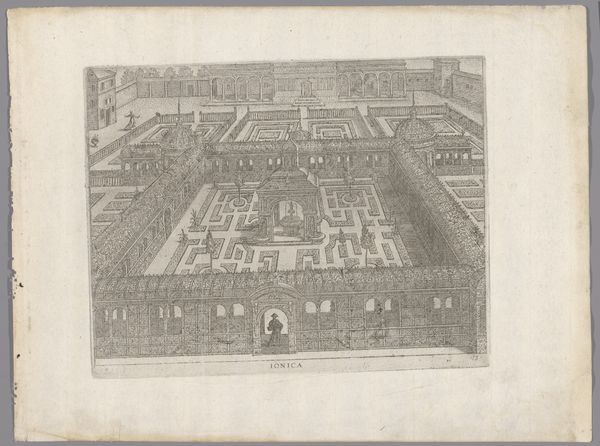

pen sketch

#

cityscape

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 352 mm, width 462 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have an intriguing cityscape from the early 18th century, "View of the Augustinian Monastery in Antwerp," likely dating from between 1727 and 1734. This engraving offers us a bird's-eye perspective of the monastery complex, rendered with a precision that invites close inspection. Editor: My first impression is how rigidly organized everything appears. From the manicured gardens to the regimented rows of houses, it feels like a very controlled environment, reflecting a particular social order. There's an air of solemnity, perhaps even constraint. Curator: That sense of control is fascinating because Baroque cityscapes, especially those depicting religious institutions, were often deliberately designed to project power and stability. The formal gardens and the imposing architecture visually reinforced the Church's authority and permanence. Also, see how the walled garden contrasts with the exterior buildings, reinforcing themes of purity, contemplation, and, arguably, isolation. Editor: Absolutely. The visual message here seems quite deliberate, an attempt to present the monastery as a pillar of the community. But, to whom was that image targeted, I wonder? Given its elevated perspective, this image would have been visible to only the highest authorities. Was this to celebrate accomplishments or mask vulnerabilities within the religious establishment? Also, there's something about the way the perspective is flattened, creating a feeling of detachment from street-level life. What is absent is as telling as what is included in the print. Curator: That’s a crucial point. We are missing, for example, any visible human expression in the scene; this makes one ponder, what message is being communicated? While it portrays the structure, it also serves as an emblematic portrait, imbuing it with the values and ideas of its time. Look how that emphasis reflects a desire to express institutional values through symbolic architectural design, a common technique in the Baroque era. Editor: Thinking about its cultural context helps unpack deeper implications embedded in this piece, and it becomes a kind of mirror reflecting the sociopolitical hierarchies. Its power is still here, centuries after its creation. Curator: Indeed. These works carry layers of visual and historical resonance far beyond their initial intent, as objects or aesthetic devices. Editor: Leaving us with enduring questions about representation, ideology, and the visual language of power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.