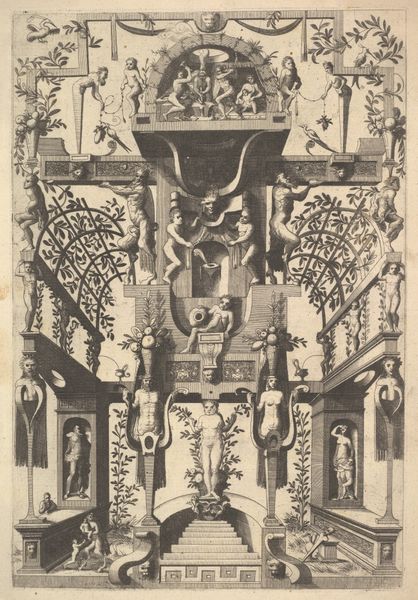

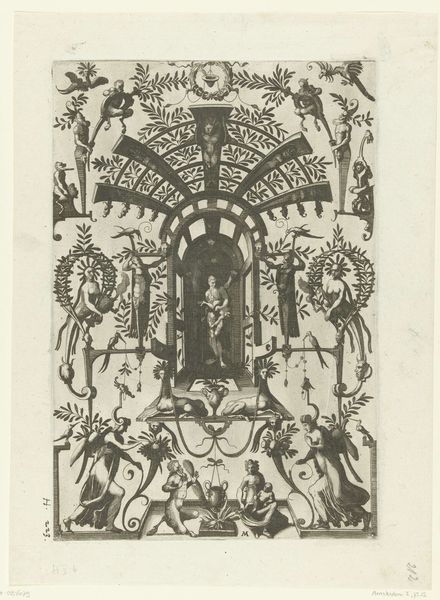

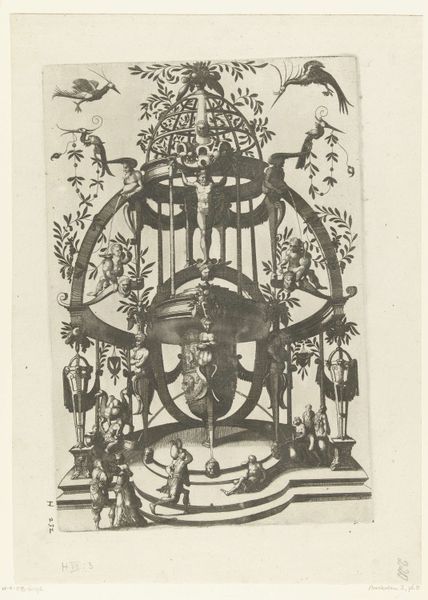

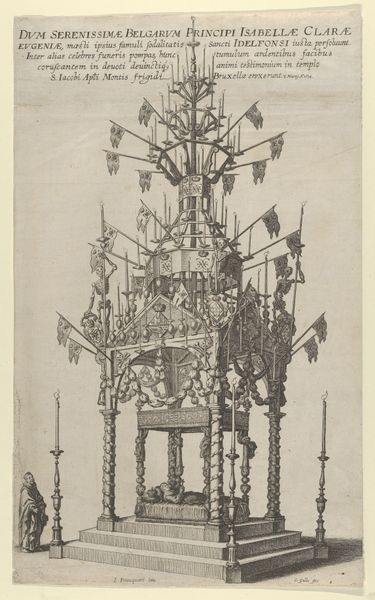

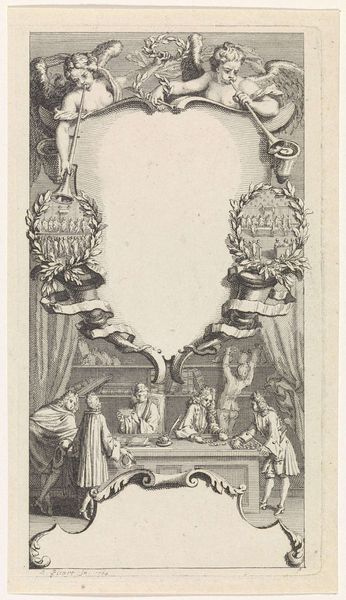

print, engraving

#

medieval

#

allegory

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

decorative-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: 11 15/16 x 8 1/16 in. (30.32 x 20.48 cm) (plate)

Copyright: Public Domain

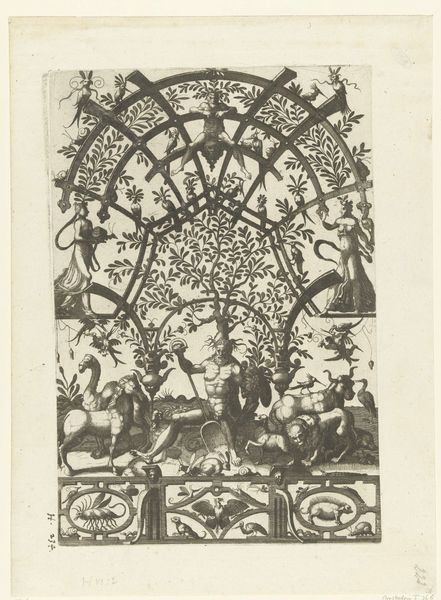

Editor: So, this is Cornelius Floris II's "Plate of Ornaments and Grotesques" from around 1556. It's an engraving and looks incredibly intricate! There’s so much going on, a real sense of overflowing detail. What stands out to you about this print? Curator: What immediately strikes me is how this piece embodies the Renaissance's obsession with classical antiquity and how that obsession functioned within the cultural landscape. We're seeing not just a revival of classical forms – the figures, the architectural motifs – but a reinterpretation filtered through a Northern European lens. Floris was hugely influential in popularizing a new style; how do you think prints like these circulated and what kind of role do you imagine they played? Editor: Well, as a print, I imagine it would have been relatively easy to distribute. Maybe it served as a template or inspiration for artisans and architects? A sort of pattern book? Curator: Exactly! These prints weren't meant to be passively admired as high art in a museum setting; they were tools, active agents in shaping the visual environment. Consider how architecture was understood at the time – not just as construction, but as a reflection of social order and civic virtue. By providing these designs, Floris was actively shaping the physical embodiment of those ideals in buildings and decorative arts across the region. The museum context almost flattens its original purpose. What about the “grotesques” that are included in the title? What kind of symbolic and allegorical function do you think they serve? Editor: That's interesting…I suppose they break up the classical order. Are they supposed to remind viewers of the complexities and less idealized parts of life, maybe? Curator: That's a great point! They are a potent reminder that even in the pursuit of harmony and perfection – ideals the Renaissance valued deeply– there is always the unruly, the chaotic. This plate then is less about pure classical revival, and more about navigating the relationship between classical ideals, and the complexities of life. Editor: It’s fascinating to think of this print as a really influential and functional object, shaping the look of its time! I never considered how powerful printmaking could be beyond just art. Curator: Precisely. It challenges our conventional ideas about what art *is* and *does*, and compels us to think about art’s engagement in everyday society.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

The Netherlands developed its own version of the grotesque, characterized by heavy, three-dimensional forms. Cornelis Floris pioneered the style in Antwerp, inspired by a visit to Rome in 1538. An architect as well as a sculptor, Floris populated this superstructure with satyrs, caryatids, terms, and masks. Some of his favorite devices are also visible--string, birds with string, holes, and figures enclosed by straps. In the upper cavity, smoke trails from Vulcan's forge.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.