print, engraving

#

portrait

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

england

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: 16 1/8 x 13 in. (40.96 x 33.02 cm) (plate)

Copyright: Public Domain

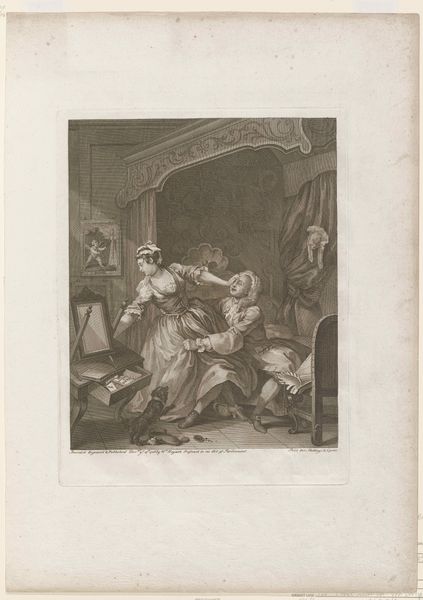

Editor: This engraving, "After" by William Hogarth, made in 1736, depicts what appears to be the aftermath of a night of passion. It seems rather chaotic. A woman clutches at the man, a wigged figure stands in the background… what's the story here? How do you interpret this work? Curator: Hogarth's series, "A Rake's Progress" critiques the social mores of 18th-century England, and we can see that playing out here. Consider the purpose of the print medium in that era: reproduction enabled Hogarth to disseminate his social critiques widely. Where do you see that critique manifesting visually? Editor: Well, the overturned table, the discarded clothing... It's a rather unflattering portrayal of aristocratic excess. There’s even a dog gnawing on something! Curator: Exactly. Hogarth uses these details to underscore the moral decay he perceived within the upper classes. Notice also the composition - the claustrophobic space, the figure lurking behind a curtain. It all speaks to a world of secrets and hypocrisy. It raises questions about social mobility. Editor: The hidden figure is unsettling. Is that the man's wife or a member of the aristocracy? Curator: It could be both. It speaks to power dynamics and social hierarchies that the wealthy men of the era are afforded in the public sphere. This piece reminds us of the art market's development during that time, especially the popularity of satirical prints among a burgeoning middle class. Did anything catch your eye that we didn’t discuss? Editor: Thinking about it as social commentary makes me see even more in it – thank you! The role of art as a mirror to society becomes clearer. Curator: Indeed, and it reveals how the narrative becomes the social currency of cultural production.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

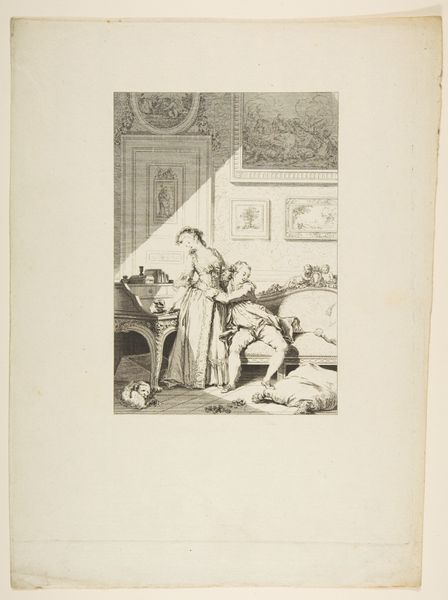

Hogarth brings his usual insightful humor to the role reversals pictured in these two images (P.68.349 and P.68.350). In Before the woman appears anxious after having invited her enthusiastic lover into her bedroom. She futilely pushes him away amid the barks of her dog. The man clings to her body wildly, his face excited and his bald head becoming exposed under his wig-a sight that in the eighteenth century carried sexual overtones. In After, by contrast, the man appears panicked and distant, and the woman now passionately reaches to embrace his fleeing figure. As was typical, Hogarth peppered his scene with details to develop his narrative further. In After a number of objects are symbolically broken-the dressing table, chamber pot, and bed curtains-and the rocket ignited by the putto in the painting in the background has been extinguished.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.