daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

16_19th-century

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

genre-painting

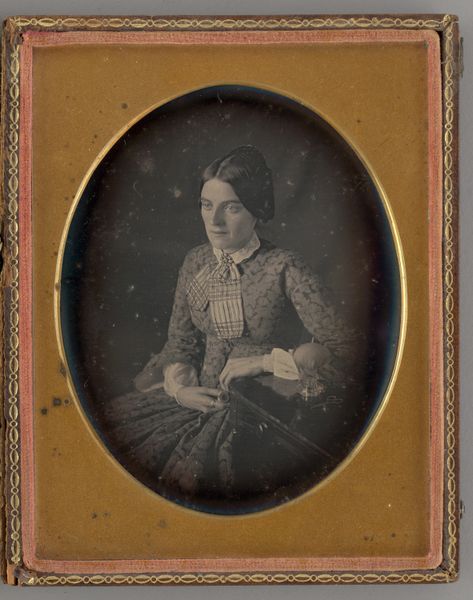

Dimensions: 7 × 8.3 cm (plate); 9.4 × 8.2 × 1.7 cm (case)

Copyright: Public Domain

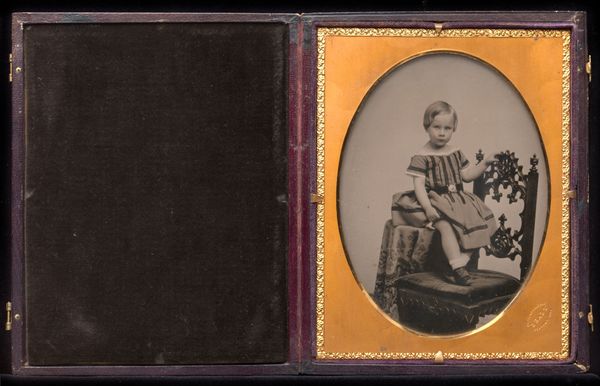

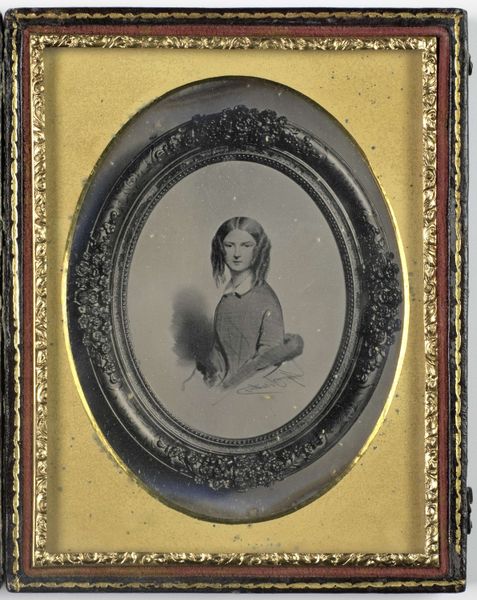

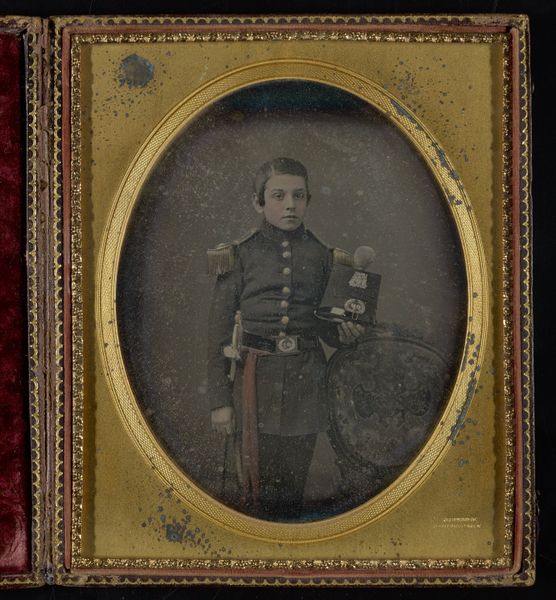

Curator: Here we have an intriguing portrait: "Untitled (Portrait of Standing Girl)," a daguerreotype from between 1853 and 1899. Editor: My first impression is… melancholy. Something about the grayness of the image combined with that stiff posture and frilly dress reads as almost oppressive. The little girl appears lost in thought or perhaps constrained. Curator: The daguerreotype was a relatively early photographic process. Think about what that meant for portraiture. Suddenly, capturing a likeness wasn't only for the wealthy who could afford a painted portrait; it became accessible to a wider range of people. Though even then, this dress might indicate an elevated status, or a moment worthy of an exceptional family splurge on presentation. Editor: It’s interesting how that accessibility is still tied to cost. We're looking at a very materially rich presentation. The gilded frame, the velvet lining... it speaks volumes about the sitter's context and how they wanted to be remembered. Also, consider how posed she must have been and for how long to allow this primitive tech to grab this single moment. It’s fascinating to reflect on labor, especially in this photographic art object. Curator: Right. These details absolutely contribute to our understanding. There is, to my eye, something vulnerable and a little heartbreaking about the subject, like we are glimpsing a secret. Notice also the minimal tonal range achievable with this technique. What colors, moods or personal narratives are summoned, for you, beyond this stark silver surface? What emotional history does it evoke? Editor: What I see is the sheer effort, even the hidden work and toxic process that this art object represents. These weren't casually snapped selfies! Every element from the silvered copper plate to the mercury fumes speaks of a different time of labor and capital, compared to how instantly gratified we now are by capturing our lives. And the frame? It speaks to a desire for permanence, but one manufactured from industrializing ornamental techniques, a moment preserved for the long term but born from so much other making. Curator: A fascinating perspective on labor and artifice that I hadn't considered. Editor: And you've helped me glimpse an intimate space, despite that distance, the almost spectral appearance, which is really thought-provoking in terms of history and emotional experience.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.