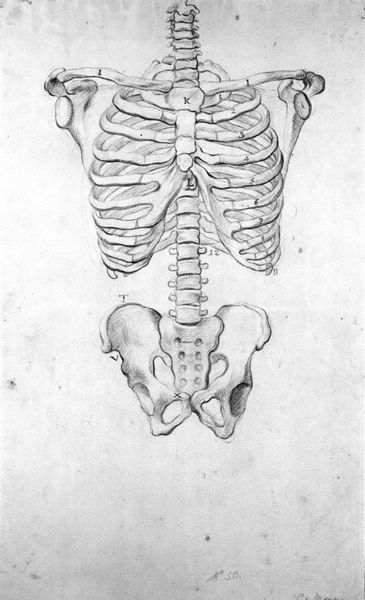

drawing, pen

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

figuration

#

vanitas

#

pen

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

Dimensions: 490 mm (height) x 344 mm (width) (bladmaal)

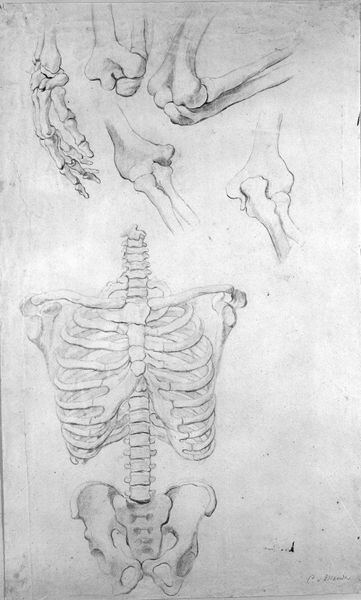

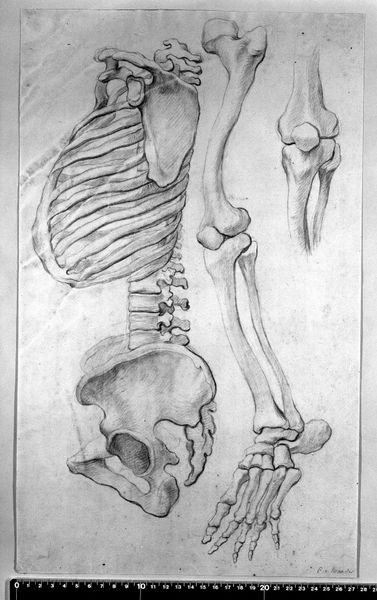

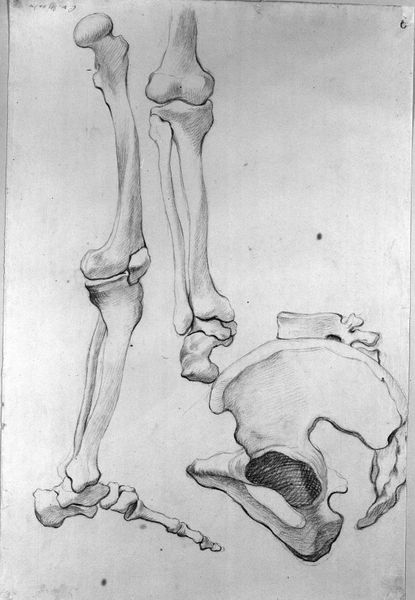

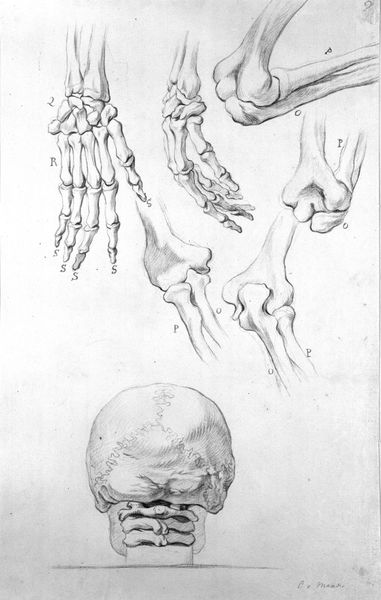

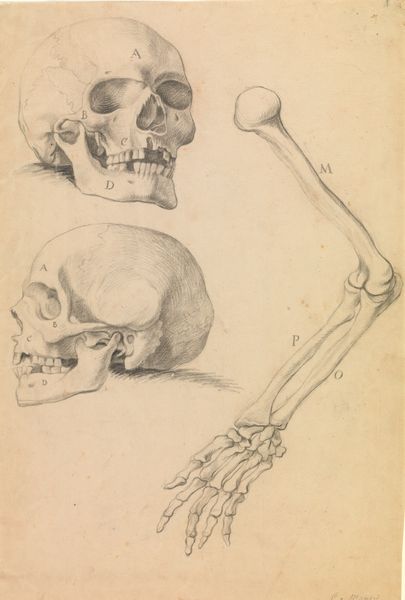

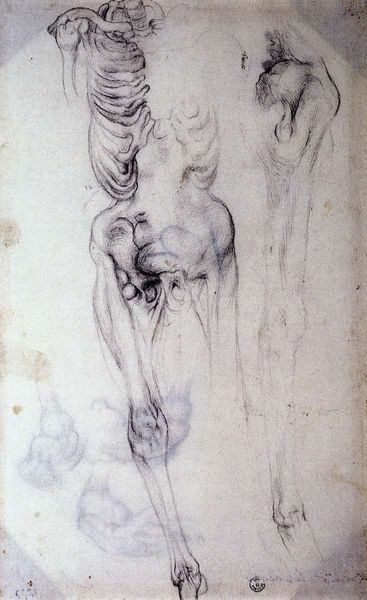

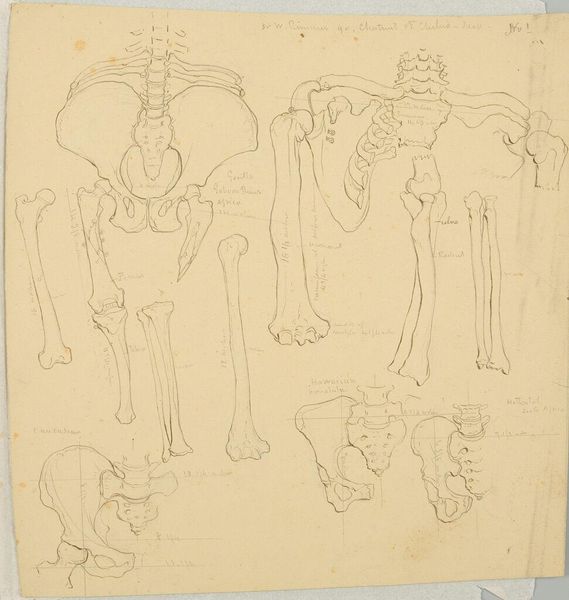

Curator: Before us is a drawing attributed to Karel van Mander III, made sometime between 1660 and 1663. The piece, rendered in pen, is titled "Two Skulls, an Arm, and a Hand." Editor: My first thought is stark. The black lines against the aged paper, the anatomical details, the inescapable confrontation with mortality...it’s unsettlingly direct. Curator: It certainly resonates with vanitas themes, popular in the Baroque era. But, thinking of the work materially, I wonder about its intended use. Was it preparatory for a larger painting? An independent study? How did the availability of paper and ink influence such works? Editor: Structurally, the composition divides itself into distinct units. Two skulls rendered from different angles establish a dialogue across the picture plane. Below, the skeletal arm echoes the orientation, and the disembodied hand on the right completes a tripartite exploration of anatomy. Curator: Precisely. The accessibility of this anatomical study must have served an important role for academic instruction at the time. Who had access to this type of knowledge, and how did that inform their social standing and influence? Editor: And the lettering superimposed onto the skulls! These notations, combined with the rigorous detail, suggest a clinical intention. Perhaps less about the "memento mori" and more about deconstructing form. Semiotically, each element contributes to the lexicon of anatomical representation. Curator: Considering artistic training, how might this type of exercise democratize art making? Allowing access to form through anatomical analysis regardless of other financial constraints or formal training through guild. Editor: I’d argue, the formal precision reinforces a hierarchy— privileging reason and observation. The lines, precise and controlled, impose order on something inherently chaotic: the disintegration of the human body. Curator: Indeed, the tension between that which can be taught through the observation and reproduction, against lived experiences… intriguing to consider for artists creating history paintings for instance. Editor: Ultimately, it provokes thoughts on the human condition. The objective representation highlights the temporary architecture we all inhabit. Curator: Thinking materially then, how did such studies serve wider artistic endeavors. Editor: Yes, food for thought.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.