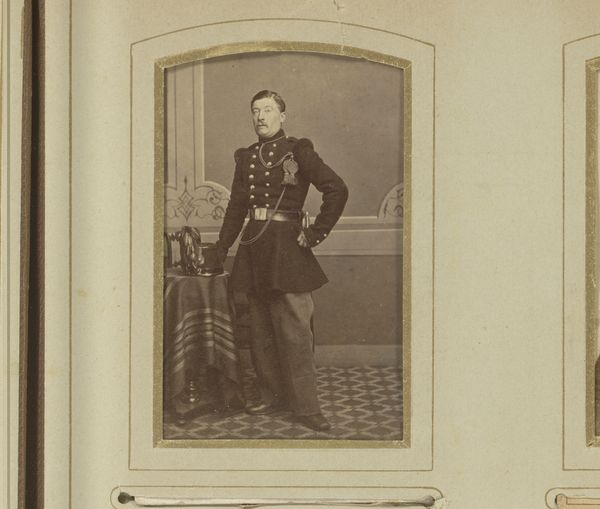

daguerreotype, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

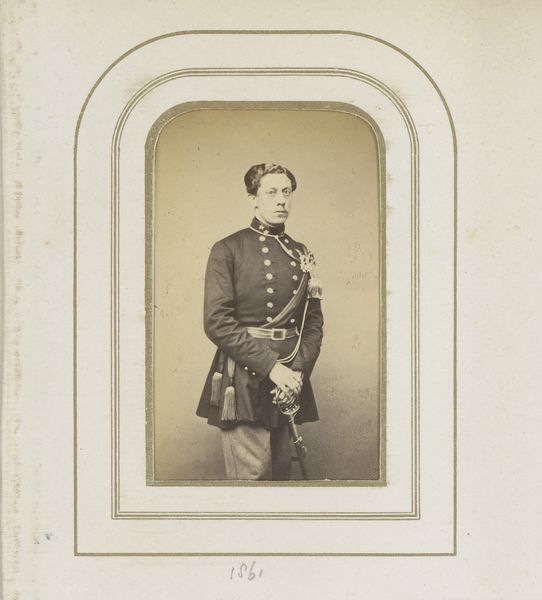

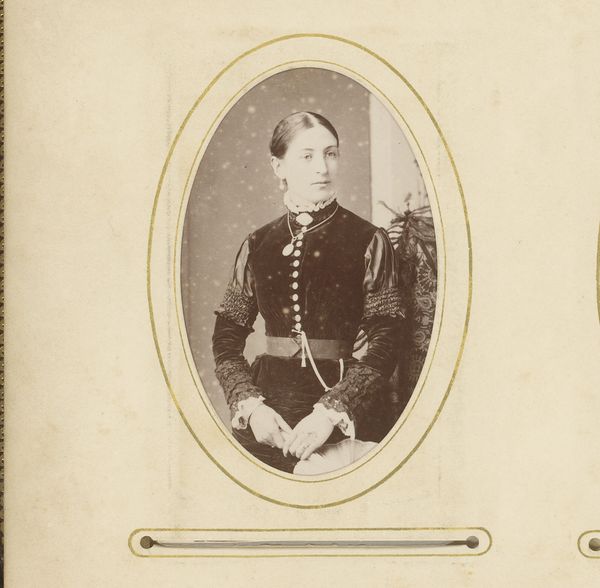

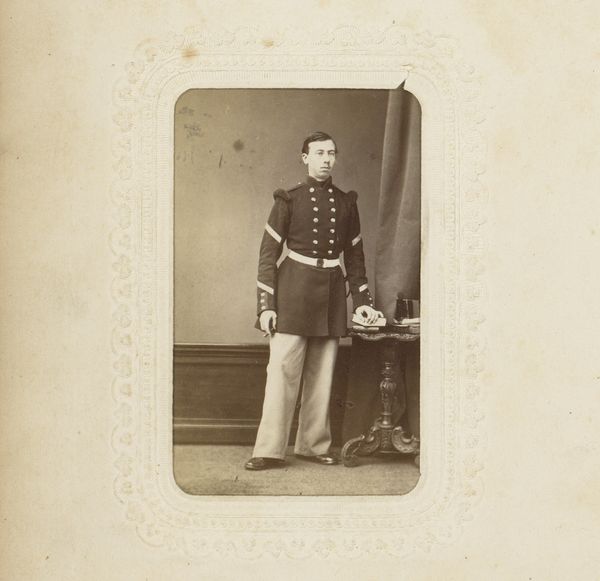

portrait

#

self-portrait

#

muted colour palette

#

daguerreotype

#

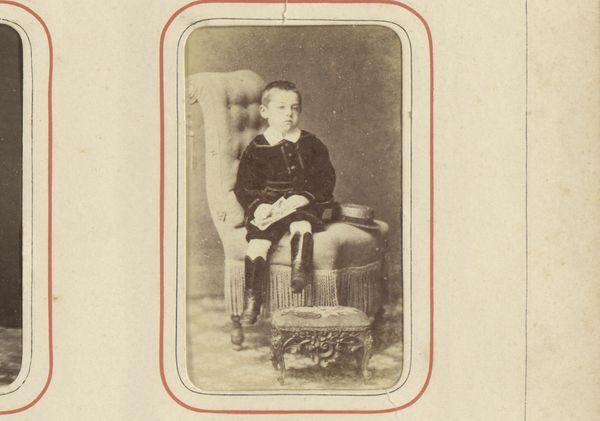

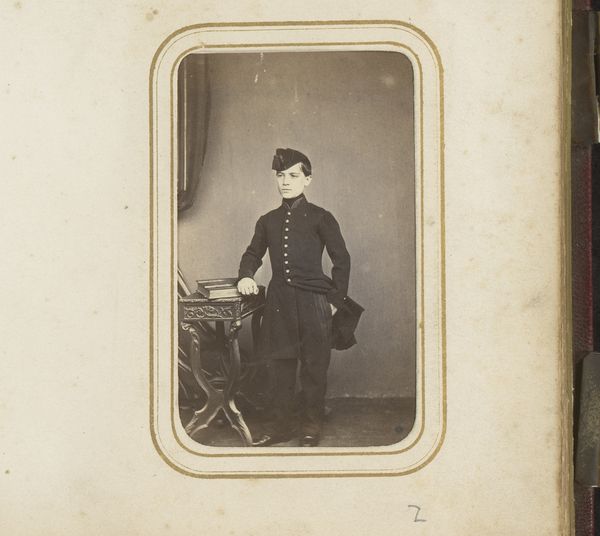

boy

#

figuration

#

photography

#

historical fashion

#

child

#

coloured pencil

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

united-states

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

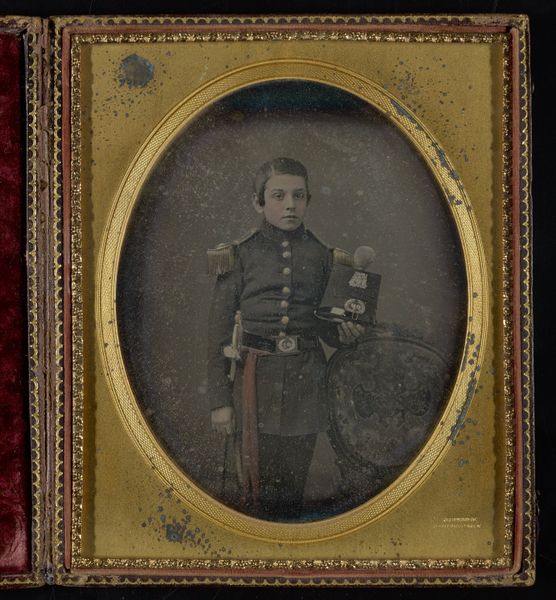

Dimensions: 14 × 10.8 cm (5 1/2 × 4 1/4 in., plate); 15.2 × 24 × 1.3 cm (open case); 15.2 × 12 × 1.8 cm (case)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: Here we have an untitled daguerreotype, "Portrait of a Boy," from the 1850s by L.H. Hale, displayed at the Art Institute of Chicago. The image quality is quite striking despite its age; it almost feels ghostly. What stands out to you when you look at it? Curator: The most striking thing to me is the power of this image to make present the complexities of childhood and representation in the mid-19th century. This wasn’t an era known for its sympathetic portrayals of children. Who was this boy, and what expectations were placed upon him in this time and place? Look at the way he's dressed, positioned...Does this sartorial imposition reflect the restrictive social roles imposed on young men? Editor: I hadn’t thought about it like that, but now that you mention it, he does seem almost like a miniature adult. The serious expression, the formal attire… it's a bit unsettling. What can we infer about the family’s social standing or aspirations? Curator: Precisely! Daguerreotypes were relatively expensive at this time, placing them outside the reach of many. The portrait itself becomes a signifier of status, doesn’t it? What’s also interesting is the boy's direct gaze. There's a sense of vulnerability, a questioning of the very act of being memorialized. Editor: It’s almost like he is aware of the historical implications of being photographed, even though that wasn’t possible back then. How might ideas about identity formation, gender, and even class consciousness shape our interpretation of this image today? Curator: Exactly! How does seeing this portrait now, in our own socio-political context, affect our perception? What does it tell us about how we've changed, or perhaps haven't changed, in how we perceive and value childhood and representation? Editor: This makes me see the image in a totally new light. It’s more than just a historical portrait; it's a statement. Curator: And a springboard for further investigation. Considering art through such frameworks allows us to truly understand the power that historical works can exert on contemporary discourse.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.