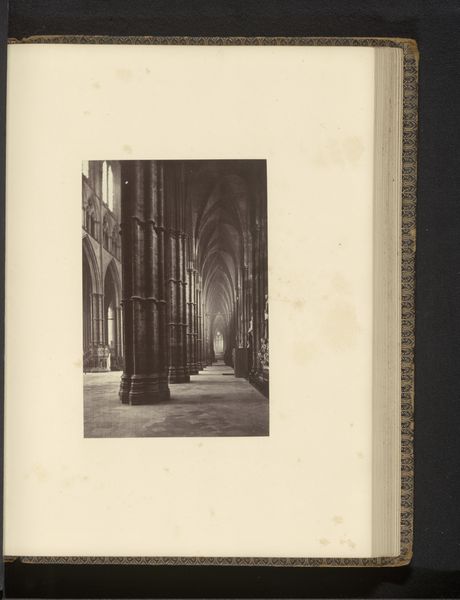

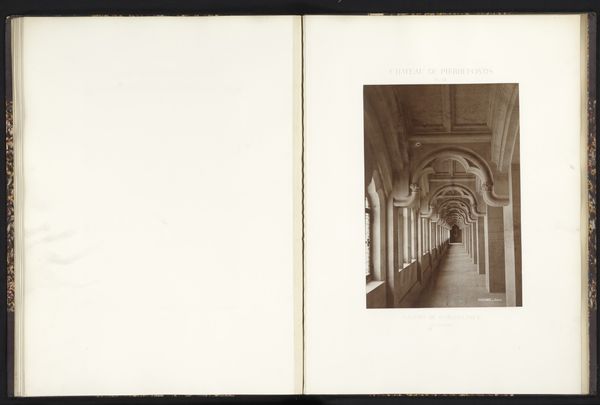

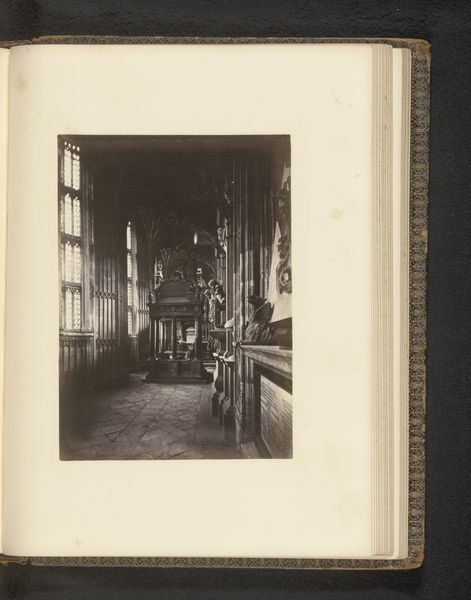

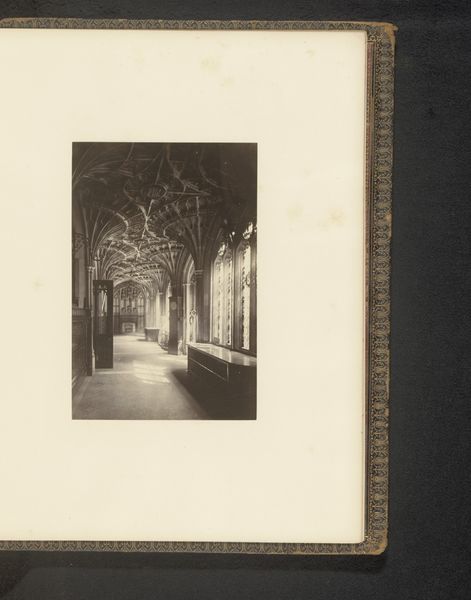

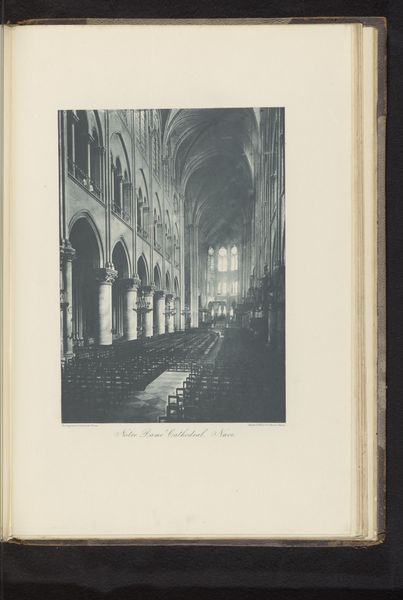

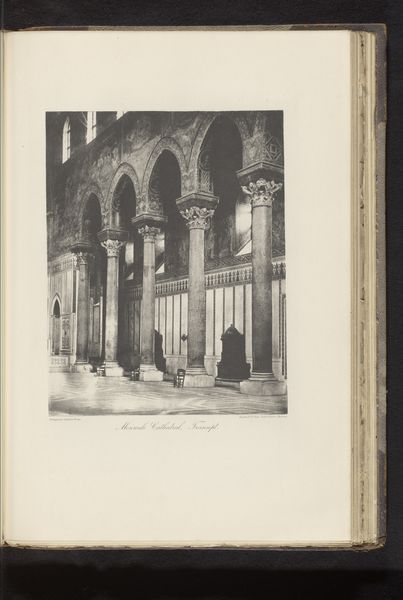

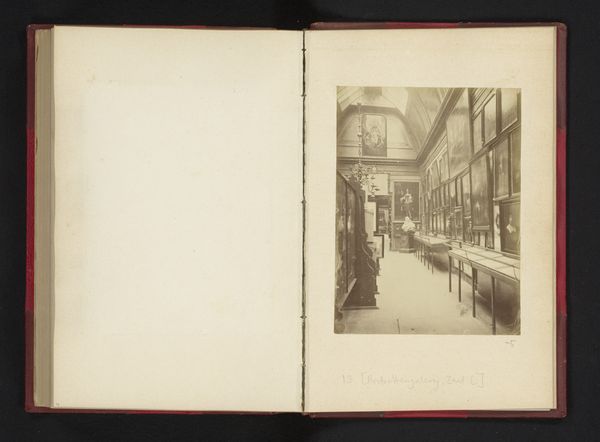

print, photography, gelatin-silver-print, architecture

#

aged paper

#

homemade paper

#

paper non-digital material

#

medieval

#

ink paper printed

#

paperlike

# print

#

sketch book

#

landscape

#

paper texture

#

photography

#

personal sketchbook

#

folded paper

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

paper medium

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 177 mm, width 125 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

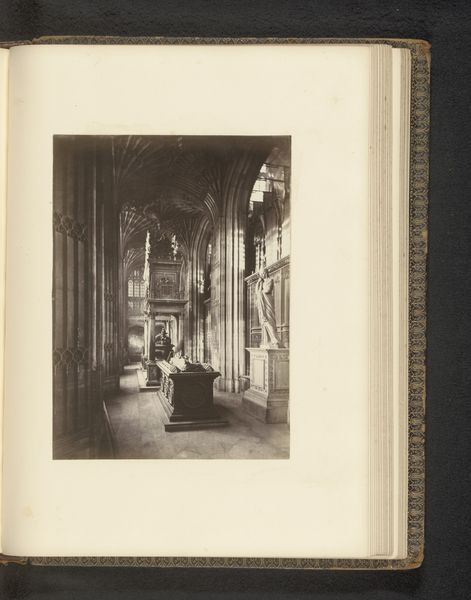

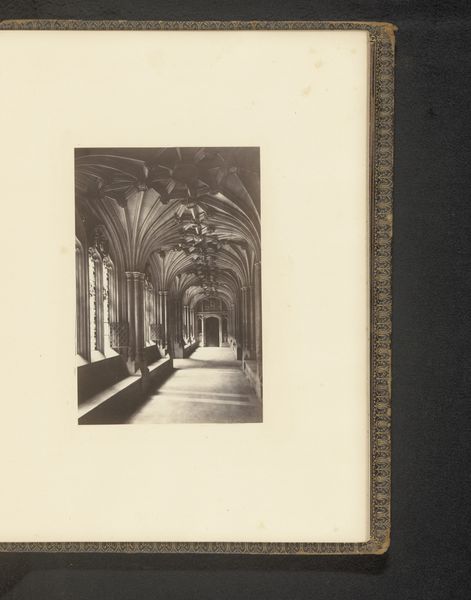

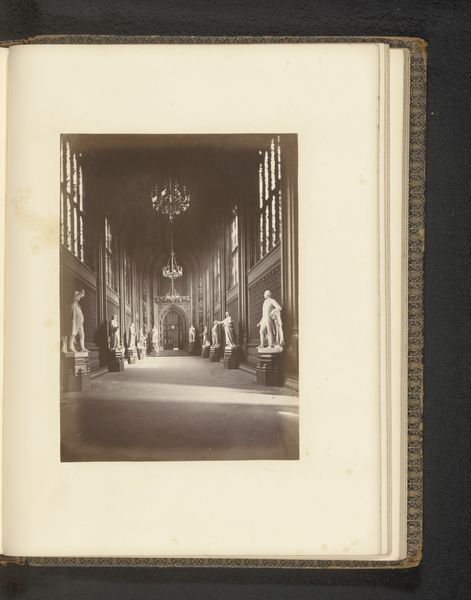

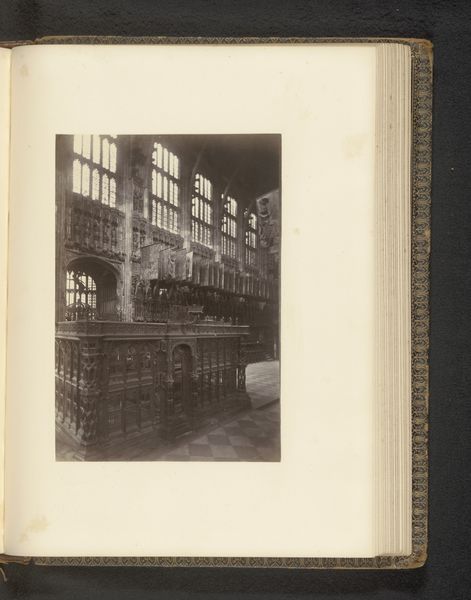

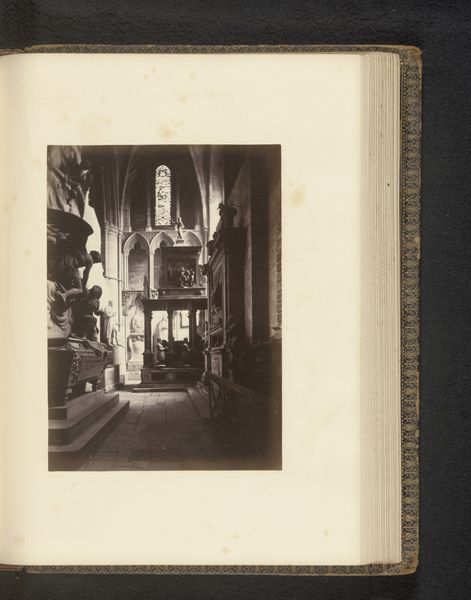

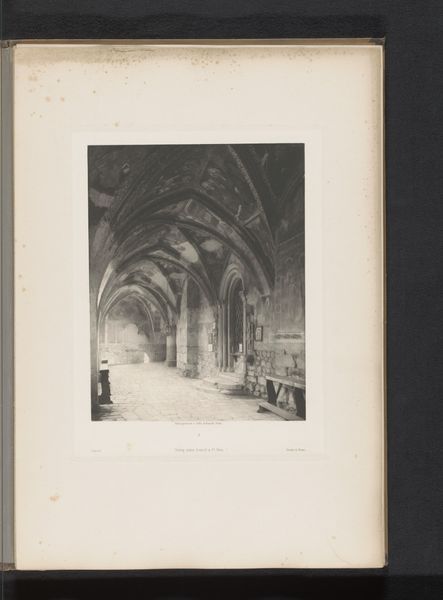

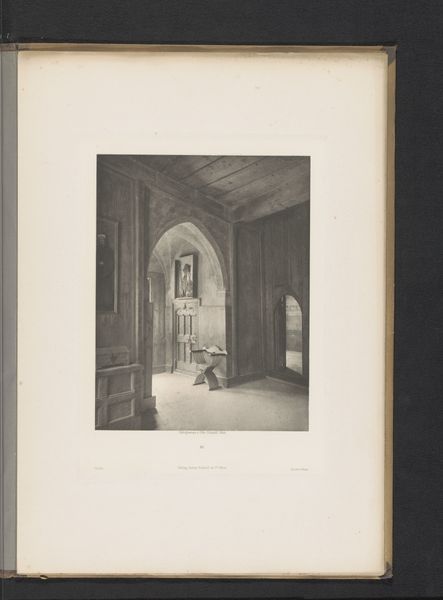

Curator: Here we have a photograph of the Chapel of Henry VII in Westminster Abbey, captured sometime before 1869 by John Harrington. It's a gelatin-silver print, mounted in what appears to be an album. Editor: Immediately, I'm struck by the silence captured within this image. The light falls so delicately on the checkerboard floor, creating this serene, almost otherworldly atmosphere. It feels quite contemplative. Curator: Yes, Harrington really understands the power of light here. What is fascinating is thinking about how images like these were disseminated, as photography was making spaces like this available to a much broader public. Think about how access to these symbols of power changes with photographic reproduction. Editor: Absolutely. It raises interesting questions about representation and access. How does making these historically exclusive spaces visible change their meaning in the larger social and political context? Is the sacred space desacralized through visibility, or does it expand to accommodate more participants? I'm particularly drawn to that delicate line between tradition and progress—and in what ways the power relations inherent to spaces such as Westminster Abbey were, or were not, shifted through this act of photography. Curator: That interplay is precisely what makes the image compelling. This building was built as an expression of Royal authority. Looking at photographs such as these encourages consideration of photography’s role in shaping perceptions of political power and history. It allows to evaluate photography as a medium that can both preserve and disrupt. Editor: And in considering whose perspectives are reflected. The photograph presents a carefully chosen, controlled view, absent of human presence. By looking at it from today’s vantage, it provides an opportunity to evaluate both visibility and its limitations within these institutional spaces, thinking critically about both preservation and perpetuation. Curator: It makes you wonder how such a carefully designed setting impacted people who accessed these kinds of space physically and socially, but now are able to access them simply through photography. Editor: Exactly, a simple viewing opens the door for us to think critically about the historical and cultural impacts and implications of visual representation of these locations and how these presentations alter space in ways that expand what we can consider the sociopolitical relevance of our history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.