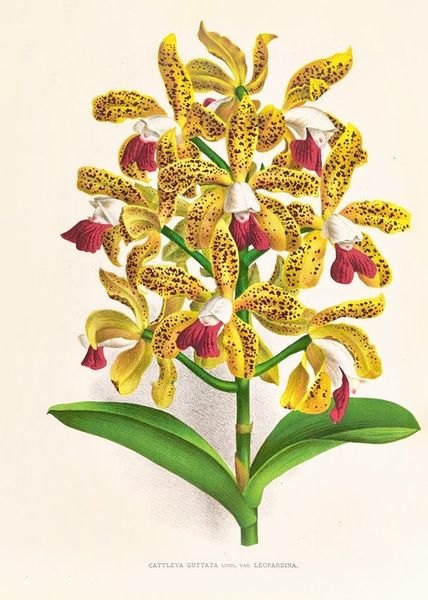

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

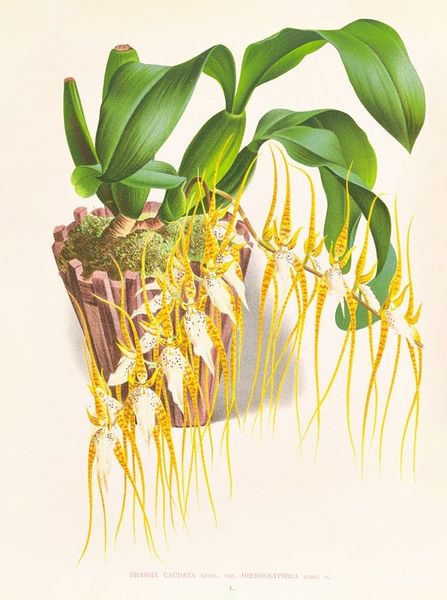

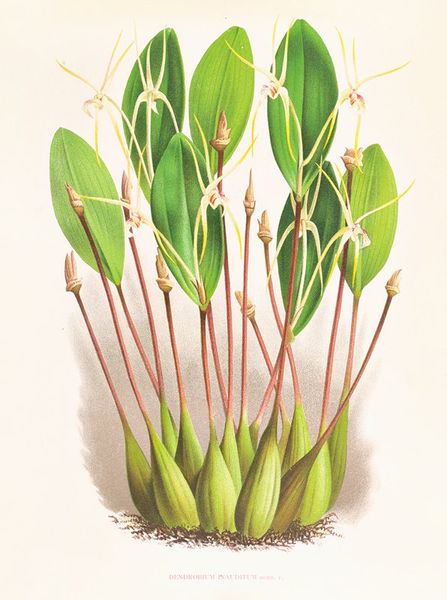

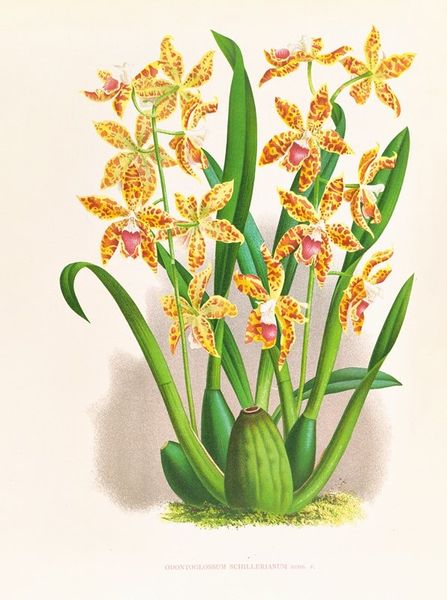

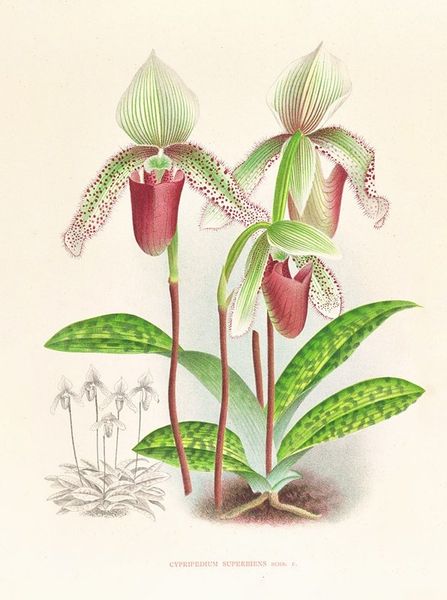

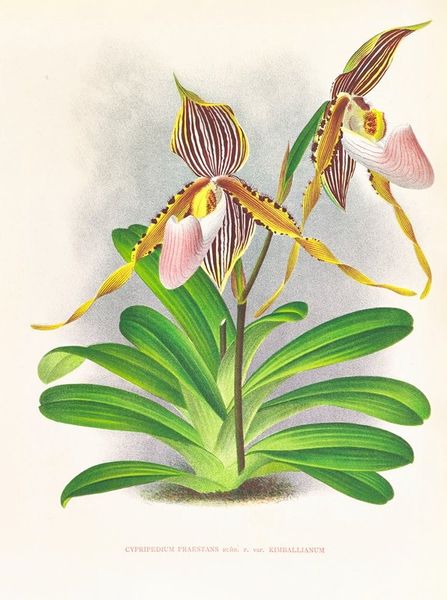

Curator: Immediately striking, don’t you think? This watercolor and print, dating roughly between 1885 and 1906, presents a vivid botanical study by Jean Jules Linden. The title is "Trichocentrum Tigrinum". Editor: There’s something so orderly about the arrangement, almost diagrammatic. It highlights the intricate detail of this flower and the curious choice to position the whole plant inside of what looks like a crude makeshift pot. It gives a feeling of imposed cultivation that makes me slightly uneasy. Curator: And yet, botanical illustrations were integral to the era’s expansionist project. Works such as Linden’s offered European audiences visual documentation, scientific classifications, asserting a type of dominance. These images helped categorize and control natural resources across colonized lands. Editor: That colonial framing is definitely part of what evokes that feeling of unease in me. It raises questions about the removal of this plant from its natural habitat to exist merely as a scientific specimen in this setting. The orchid itself seems to resist this imposition—note the untamed arrangement of the flowers. The leaves burst upwards, as if straining towards freedom. Curator: The artistry also reflects scientific rigor, however. Note the precision in rendering the leaves, the careful depiction of the orchid’s spotted petals. It underscores the scientific value placed on accuracy. It fits neatly into the nineteenth-century obsession with classifying and archiving the natural world. Editor: But doesn’t the choice of watercolour, this inherently fluid and expressive medium, introduce a layer of subjectivity? It elevates the scientific to an artistic pursuit, revealing a deeper layer of human interpretation influencing even supposed objectivity. Curator: Indeed. It encapsulates the complex relationship between scientific pursuit and aesthetic expression prevalent during its time. It reflects broader European power dynamics and our enduring attempts to capture, control, and, hopefully now, understand and protect the planet’s biodiversity. Editor: I am left reflecting on how botanical illustrations can be framed as both art and acts of control, inviting questions about preservation versus exploitation. The duality provides such a richer, complicated understanding.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.