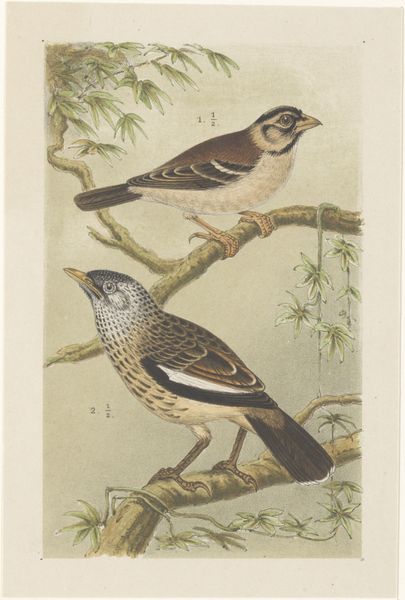

drawing, watercolor, ink, pen

#

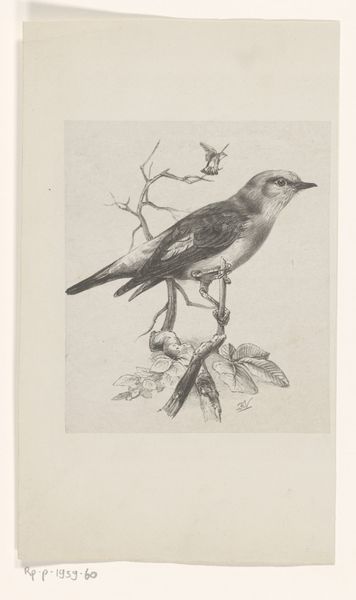

drawing

#

landscape

#

watercolor

#

ink

#

england

#

animal portrait

#

pen

#

watercolour illustration

#

watercolor

Dimensions: 11 3/4 x 9 3/4 in. (29.85 x 24.77 cm) (image)13 5/16 x 11 3/4 in. (33.81 x 29.85 cm) (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Ah, "Troupiale" by William Hayes, dating back to 1798. It’s currently part of the Minneapolis Institute of Art collection. He employed watercolor and ink, primarily in a drawing format. Editor: Striking! The contrast between the bright orange plumage and the stark black markings is captivating. It's such a focused composition; the bird's perch seems deliberately rendered to draw our eye to the animal's portrait. Curator: Hayes was an English artist known for his meticulous depictions of birds. These detailed animal portraits often served scientific and documentary purposes, so while it might seem "artistic", its initial function involved categorization and dissemination of zoological information. The materials—watercolour and ink on paper—were easily portable for an artist traveling and recording species. Editor: Yes, I wonder about the social context of creating these bird portraits, and if the aim was always to serve science. Was it intended for the consumption of elite scientific societies, or did it play a role in popular culture as well, feeding into the rising curiosity surrounding natural history at the time? Who were these images made for? Curator: Both, probably! Think about the lineage: naturalists, explorers, and artists were intertwined. Hayes's ability to accurately portray the textures of the feathers, through the precise application of watercolor washes, gave these images value beyond just mere representations. His labor—the skill and time investment—affected the final value and impact. Editor: That makes me think about the role institutions play. How does its placement in the Minneapolis Institute of Art change its reception today, versus how it might have been viewed in its own time or as a naturalist's document? Its display choices affect perception—framing, lighting, other nearby artworks all affect the power dynamic between observer and art object. Curator: Precisely. And that impacts what survives and what's celebrated. We preserve this "animal portrait," celebrating the fine application of watercolour but not necessarily interrogating England's expansion and this practice as a tool for that endeavor. Editor: I see how carefully observing process, as you point out, can raise questions about how labor, the history of naturalism and the institutions interact in art history. Curator: Exactly. "Troupiale" offers an invitation into a much larger consideration of art and knowledge, art and exploration, art and colonialism, even. Editor: Absolutely, it’s prompted thoughts regarding categorization, power and the artistic record.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.