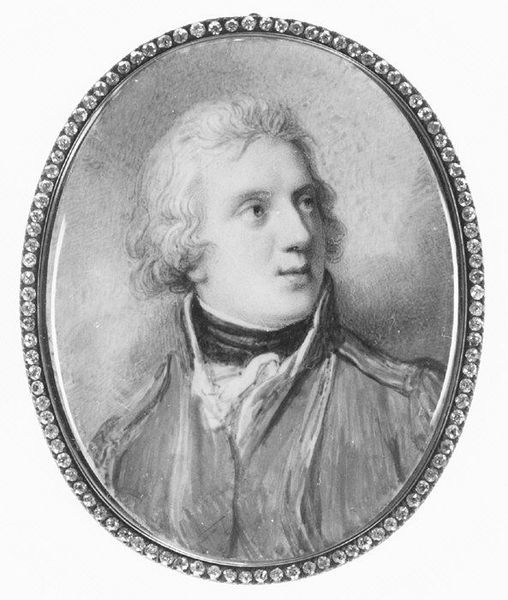

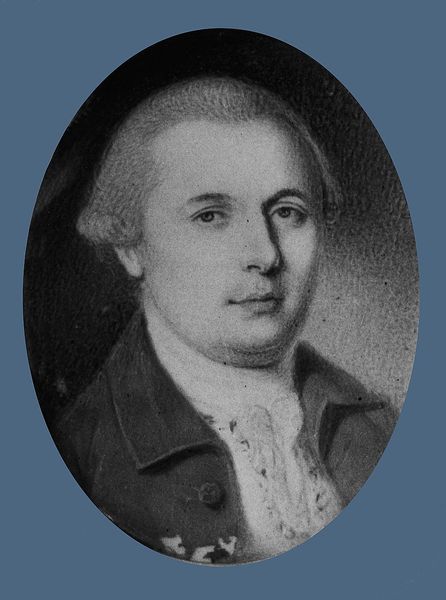

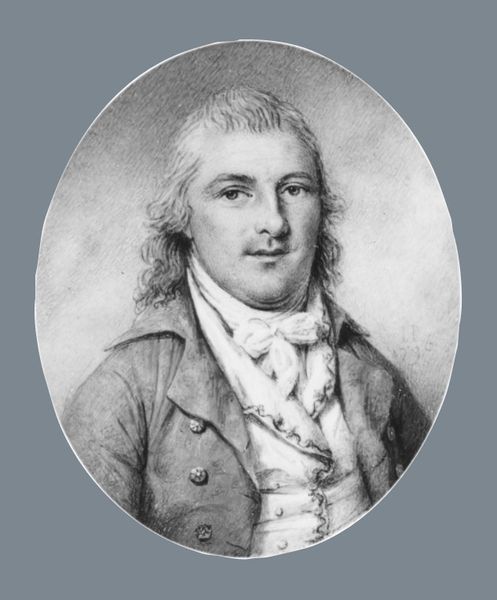

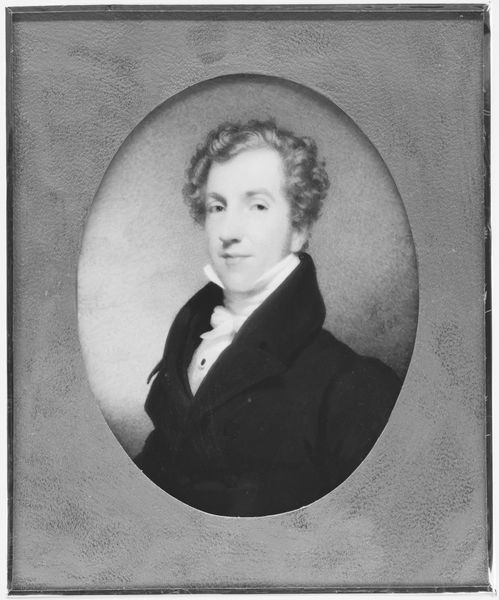

drawing, graphite, ivory

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

#

graphite

#

ivory

#

realism

Dimensions: 8.8 cm (height) x 8.5 cm (width) (Netto), 18.5 cm (height) x 18.5 cm (width) x 2.4 cm (depth) (Brutto)

Curator: Here we have "Portrait of an Unknown Gentleman," a miniature graphite drawing on ivory from around 1800, currently held at the SMK, the National Gallery of Denmark. Editor: There's an immediate sense of intimacy. It’s a direct, almost pleading gaze from this gentleman, amplified by the small scale of the ivory. Despite being black and white, it feels quite emotive. Curator: Absolutely. The piece resonates strongly with the prevailing Neoclassical aesthetic, yet maintains a footing in Realism through the stark depiction of the subject's physiognomy. Portraiture of this nature served vital roles. Editor: It makes me wonder what a portrait signified in that era, what did it mean to be immortalized in such a format, and the symbolisim invested in the details? Look at the ascot, for instance, a soft and intricate symbol of elegance. It projects an air of confidence and cultivation, typical of the time, but does it veil something? Curator: Very possibly. Such commissioned pieces not only immortalized the sitter but also transmitted and affirmed their societal standing and political allegiances. While he’s no Napoleon, portraits played into constructing and consolidating an ideal. It mattered what you chose to showcase through art. Editor: The identity being "unknown" certainly complicates things. Without that critical information, the portrait takes on this more abstract, symbolic reading. He almost stands as a placeholder for aspiration during the Neoclassical era. The visual representation is what endures, transforming our understanding into something new. Curator: Precisely. That transformation over time is what's critical for us. The "unknown" becomes, paradoxically, more universal through lacking a specific, fixed societal positioning. Editor: The drawing holds a quiet mystery, and it speaks volumes about memory, loss, and the stories images silently carry across centuries. We assign new meanings because what matters is this enduring human need to capture and preserve. Curator: Yes. And its current context—within a national collection like the SMK—allows new audiences to rediscover it, layering fresh narratives onto it, proving that images, like history itself, are never really fixed.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.