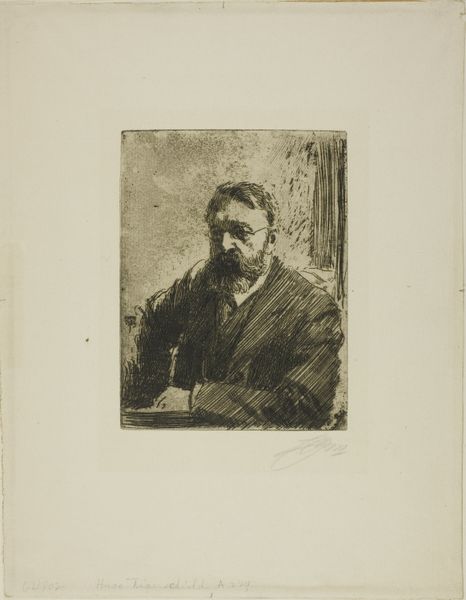

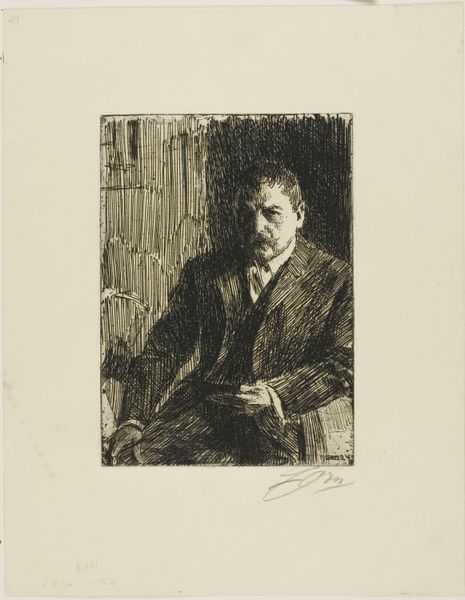

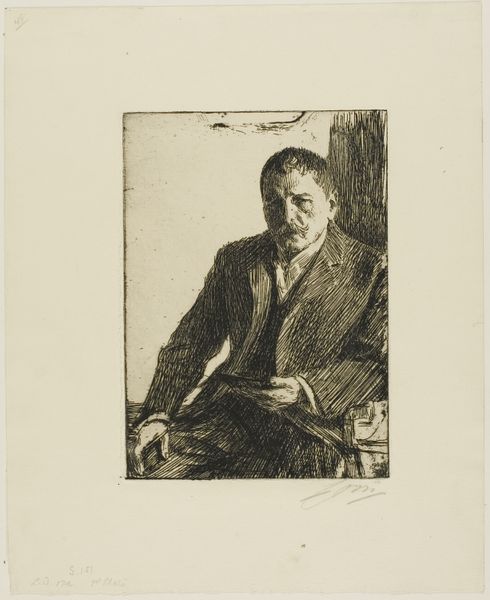

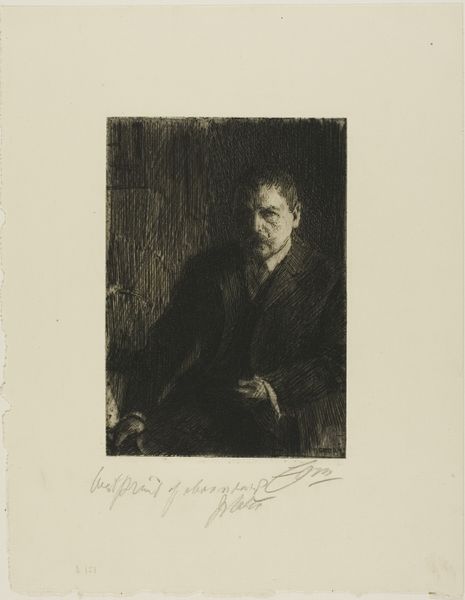

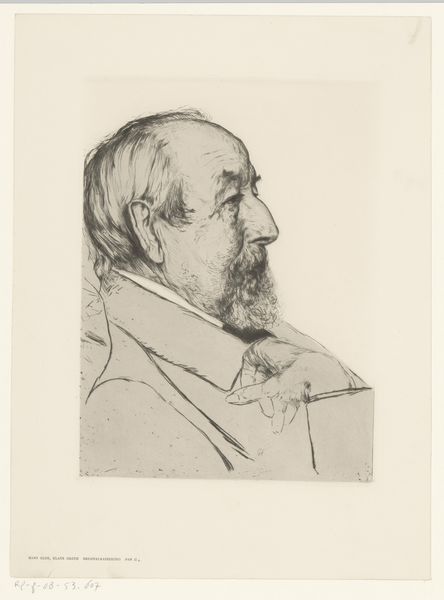

Dimensions: 130 × 88 mm (image/plate); 242 × 159 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

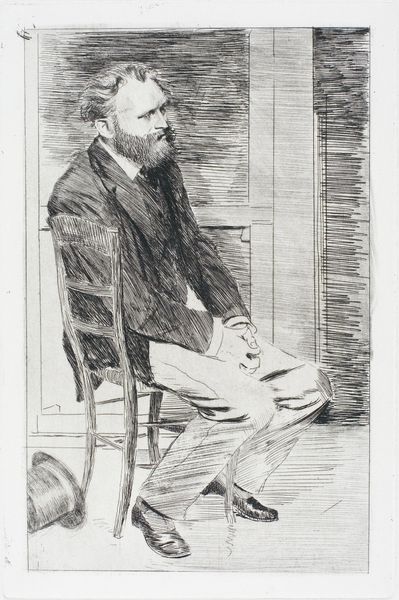

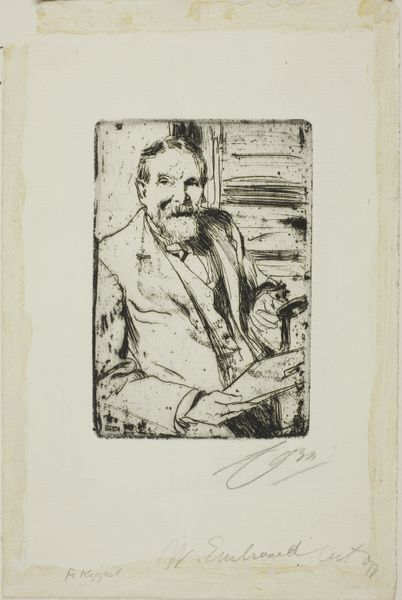

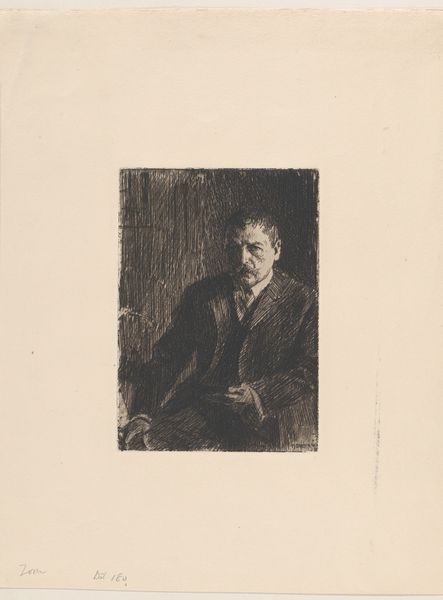

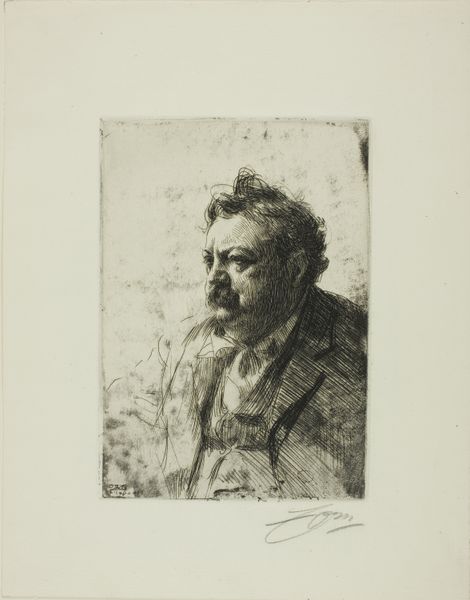

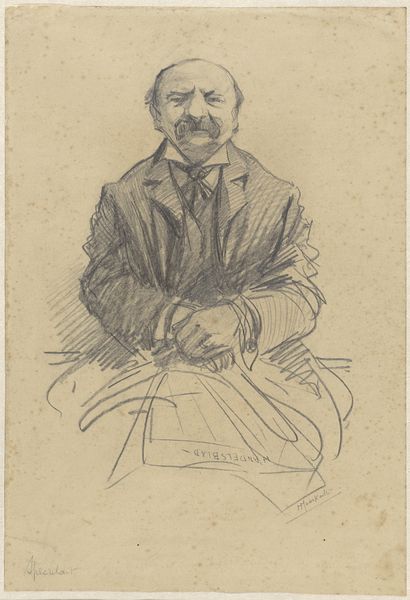

Editor: So, this is Anders Zorn’s etching, “Frederick Keppel I,” from 1898. It’s a portrait, a small print on paper. It has this immediacy because you can see all the sketchy lines from the etching process, which feels really modern. What do you see in this piece? Curator: Beyond its obvious qualities as an impressionistic portrait of an art dealer, I see a negotiation of power and class anxieties at the fin de siècle. Consider the historical context: printmaking allowed for broader access to art, challenging traditional hierarchies. Zorn, already an established artist, is depicting Keppel, who mediated the art market. What does it mean for an artist to immortalize his dealer in this way, using a medium that democratizes art? Editor: So, it’s not just a straightforward portrait. Curator: Not at all! The choice of etching itself becomes a statement. The rapid lines and unfinished quality mirror the changing social landscape. Keppel, in his suit, becomes almost like a symbol of the commercial forces shaping the art world. Consider, too, the gaze. Where do you feel it places you, the viewer? Editor: Hmm, his gaze is direct but also a little distant, which makes him seem powerful, I suppose, but approachable too. Is it Zorn suggesting a commentary of his impact of class? Curator: Exactly. How does a person of a different status, the artist, challenge someone of power through its artistic rendition and style. Editor: I see how looking at the historical moment can reshape our understanding of what appears to be a portrait. Curator: Precisely. Art doesn't exist in a vacuum. By engaging in critical discussions, it becomes a powerful instrument to investigate those power structures.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.