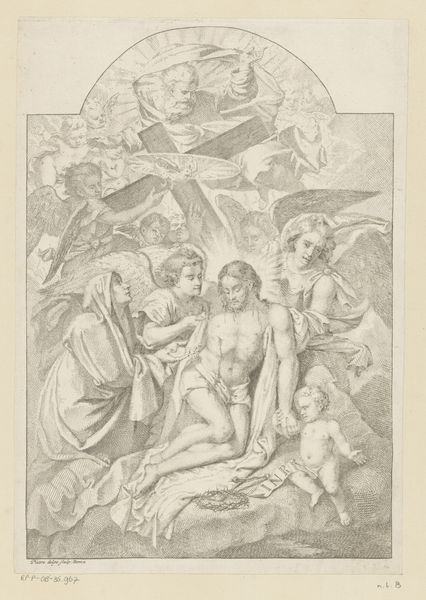

drawing

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

figuration

#

pencil drawing

#

christ

Dimensions: 5 13/16 x 3 5/8 in. (14.7 x 9.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This drawing is “Christ in Glory,” a piece created by Johann Wolfgang Baumgartner between 1732 and 1761. It resides here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: My first thought? It’s overwhelmingly Baroque! The swirling figures and the dynamism – it's got that operatic feel to it. The use of what seems to be primarily pencil lends itself to the tone as well, a preliminary sketch with all its raw energy on full display. Curator: It’s remarkable, the range Baumgartner achieves with simple graphite. He must have built the composition carefully, using layered applications, cross-hatching, and varied pressure to craft that sense of depth and texture. I am also interested in the function of drawings like this: preliminary design sketches often used for a larger composition. Did this drawing assist Baumgartner in securing a commission for a larger painting, sculpture, or fresco? Editor: Right! And think about where those larger works would typically be placed: churches, palaces, spaces of power and influence. This little sketch, this exercise in pencil on paper, becomes a critical piece in that larger cultural machinery. Religious iconography wasn’t just about personal devotion. It was about communicating and solidifying power structures, visually and spatially. This artwork existed because powerful people and religious leaders found utility in promoting their status through visual imagery, influencing behaviors of devotion. Curator: Yes, there is clearly much labor represented by many to bring such visions to light! But speaking materially, that smooth paper must have felt remarkably luxurious, perhaps even revolutionary compared to traditional parchment used in earlier devotional images. And considering that graphite becomes ubiquitous later within industrialized contexts, as pencils become readily accessible due to industrialization, Baumgartner's time saw an interesting cultural transition where newly developed and disseminated materials changed not only how we consumed, but produced images. Editor: Precisely. So what appears as just a preliminary sketch actually embodies larger social, political, and economic transformations taking shape at that time. It reflects evolving devotional imagery as part of visual propaganda within the Church as a response to rising secularism. Curator: I appreciate how you connected the material's shift to changes in its symbolic use and overall societal impact! I will keep this interpretation in mind. Editor: Gladly! It enriches the narrative, doesn't it? And reveals how even seemingly simple images have much broader societal implications to consider.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.