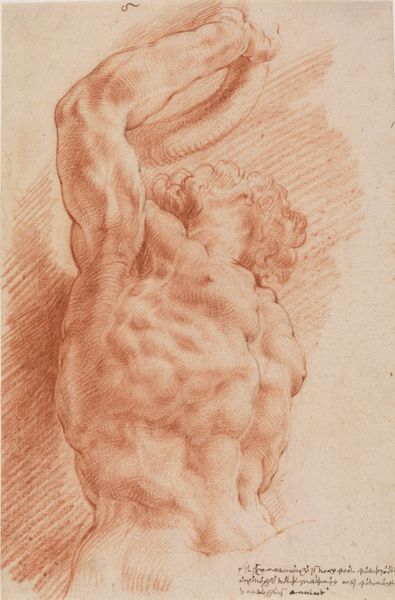

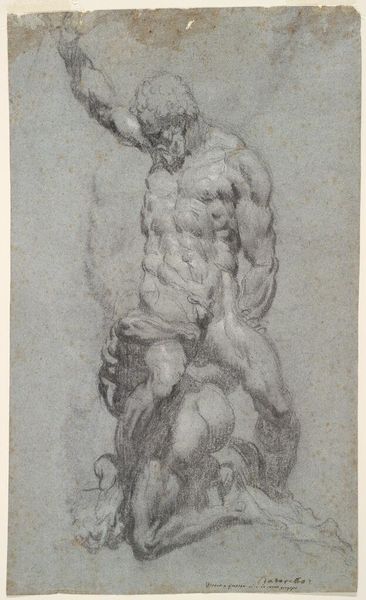

drawing, sculpture, graphite, charcoal

#

drawing

#

sculpture

#

charcoal drawing

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

sculpture

#

graphite

#

charcoal

#

history-painting

#

charcoal

#

graphite

Dimensions: 449 mm (height) x 290 mm (width) (bladmaal)

Curator: This intense graphite and charcoal drawing captures a powerful moment, it's a copy after Rubens of the classical sculpture Laocoon, placing it somewhere between 1600 and 1640. It resides here at the SMK, Statens Museum for Kunst. What are your immediate thoughts? Editor: The sheer muscularity leaps out – a study in torsion and agony. The way the light catches those straining muscles is almost unbearable, it feels like a physical assault. It is such a monumental sense of struggle captured on paper, all in monochrome. Curator: It’s worth considering that Rubens, steeped in the humanist traditions, would have viewed the Laocoon sculpture as the epitome of human suffering and resilience. This copy, even removed from the original context of the Trojan War, still resonates with profound themes. It prompts reflections on power, oppression, and the vulnerability of the human body. Editor: Precisely. I find it impossible to separate this image from discussions surrounding the body as a site of struggle – historically, religiously, politically. Consider the era – early 17th century. Who had the power to portray, to sculpt, to immortalize such forms? Whose stories were being told, and whose bodies were erased or demonized in the process? The whiteness, the idealization, these choices inherently reinforce power dynamics. Curator: True. However, the act of copying itself suggests a democratizing impulse, or perhaps a didactic one. It’s Rubens engaging with and disseminating classical ideals. And think about the function of drawings within artistic workshops at that time. Copies allowed artists and their assistants to study and learn from established models. But I do see the tensions inherent in representing idealized bodies at a time of massive social and political upheaval. Editor: Indeed, but is this representation only an aesthetic appreciation? I wonder if the visual drama might unconsciously reiterate prevailing biases in society: who embodies the ideal and therefore is seen as more deserving of recognition or agency? The way the body strains, writhes even, speaks not just to classical ideals of male form, but speaks to a very violent tension as well. The act of re-creating this scene also means re-inscribing the violence inherent in it, wouldn’t you say? Curator: Certainly, a valid point. And while Rubens likely sought to elevate the human spirit through classical allegory, we cannot overlook the fact that this portrayal of pain and suffering, removed from its historical context, carries complicated baggage. Editor: Ultimately, a powerful reminder that art, even copies, are always enmeshed within networks of power and representation. Curator: Yes, and by interrogating that entanglement, we unlock further understanding.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.