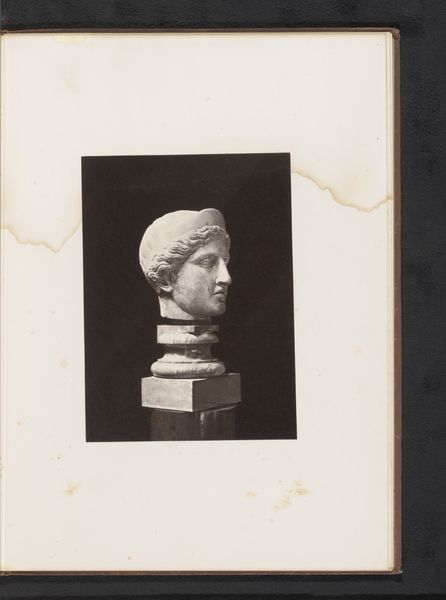

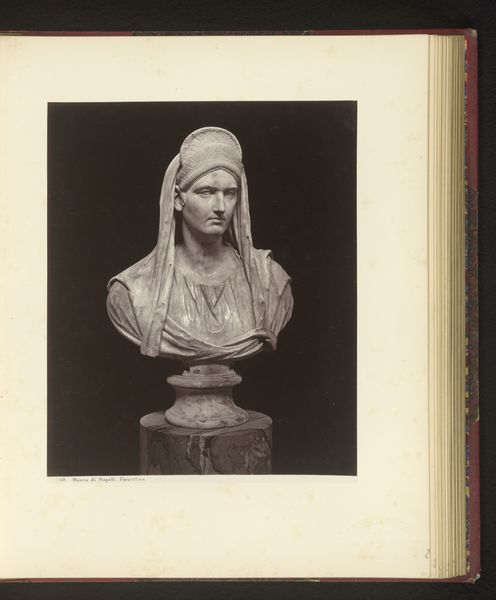

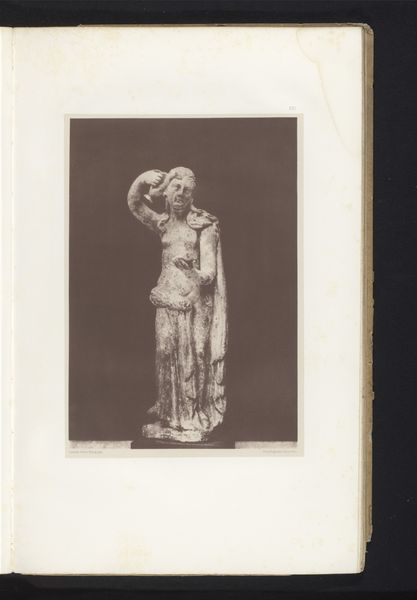

Hoofd van het beeld van Pallas Athena, afkomstig van het fronton van de tempel te Egina c. 1875 - 1900

0:00

0:00

adolphegiraudon

Rijksmuseum

photography, sculpture, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

greek-and-roman-art

#

classical-realism

#

photography

#

sculpture

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: height 257 mm, width 199 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a gelatin silver print from around 1875-1900 by Adolphe Giraudon. It captures the head of a sculpture of Pallas Athena, which originated from the Temple at Aegina. Editor: My first impression is one of austere power. The stark contrast between the figure and background intensifies the feeling. I notice the deliberate craftsmanship, every curve of the helmet is precise. Curator: Indeed, and it is worth remembering how the original sculpture was quarried and carved; it was a collective endeavor involving artisans, tools, and modes of production quite unlike what we find here with Giraudon's lens and darkroom. The image allows us to reflect upon how different methods create different perspectives, imbuing meaning with unique sensibilities. Editor: Absolutely. The photograph transforms the monumental sculpture into a portable object of study and reverence. Yet this image has a deeper resonance when we consider Athena's identity. She emerges as both a fierce warrior and symbol of wisdom, a potentially problematic union when thinking about modern concepts of power. This sculpture and its photograph, therefore, engage with debates about agency and idealized representation in Western history. Curator: Interesting observation. Shifting the discussion toward materials and processes for a moment, it's important to consider the photographic method: a layer of silver, suspended in gelatin, transforming light bouncing off a stone sculpture into a permanent artifact. These raw materials extracted from the earth undergo significant transformation through industrial chemical means. Editor: I see it as connected to issues of cultural appropriation. Ancient artifacts become resources. It opens a discussion regarding labor and the social conditions under which artworks, ancient and modern, circulate as symbols of cultural and political capital. How do the dominant structures, power structures within which such practices exist, shape our understanding? Curator: Well, both capture a dialogue across eras, engaging conversations concerning method, raw materials, meaning, power and cultural identity that are perpetually changing over time. Editor: Precisely, viewing it through these perspectives encourages continuous dialogue, enriching the appreciation of both artistic expression and its social implications.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.