Copyright: Public domain

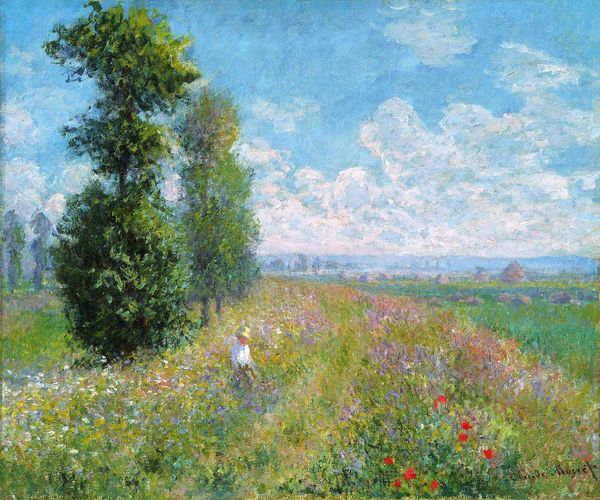

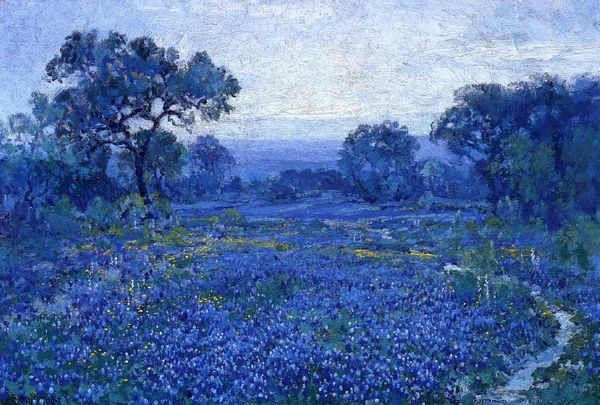

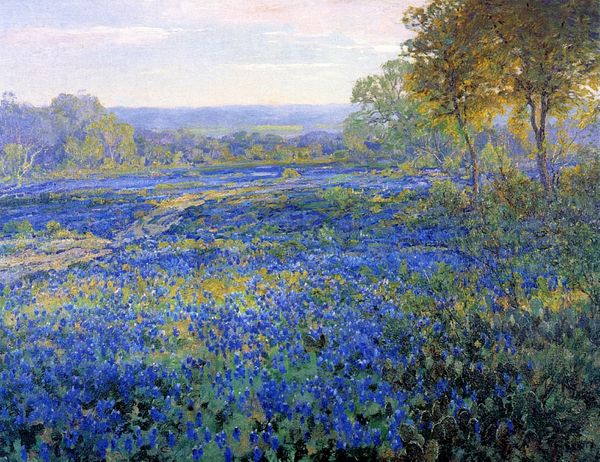

Editor: So, this is Robert Julian Onderdonk's "Bluebonnet Scene with a Girl," created around 1920 using oil paint. It's quite dreamy. What stands out to me is how the girl almost blends into the bluebonnets, like she's part of the landscape itself. How do you interpret this work? Curator: I see this as a potent engagement with the processes of labor and landscape. Note the repetitive mark-making of impressionism: mass production and commodification, even of pastoral scenes, mirroring the industrialization reshaping early 20th century America. How do these 'bluebonnets' become an asset, and what sort of material relationships – agriculture, tourism – are implied here? Editor: So you're saying it's less about a pretty landscape and more about… work? But the colors are so soft, almost idyllic. Curator: Exactly. That 'idyll' is manufactured. Consider the materiality of oil paint itself - mined, processed, packaged. It becomes another industrial product representing nature in a carefully constructed manner. The bluebonnets themselves may symbolize an almost aggressive commodification of "Texas-ness." Editor: That's a much darker reading than I expected! So, is the "Girl" also part of that commodification? Curator: Possibly. How might she, and this painting of her, be contributing to a marketable and consumable version of regional identity? The material conditions are coded, subtly. Editor: I never would have considered that perspective, focusing on materials and manufacturing. It really makes me rethink how landscapes, even beautiful ones, can be connected to larger economic systems. Curator: Indeed. Hopefully you'll never view pretty scenery the same way again. Editor: Thanks for pointing that out! This conversation has definitely offered a new understanding of how materiality impacts our reading of art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.