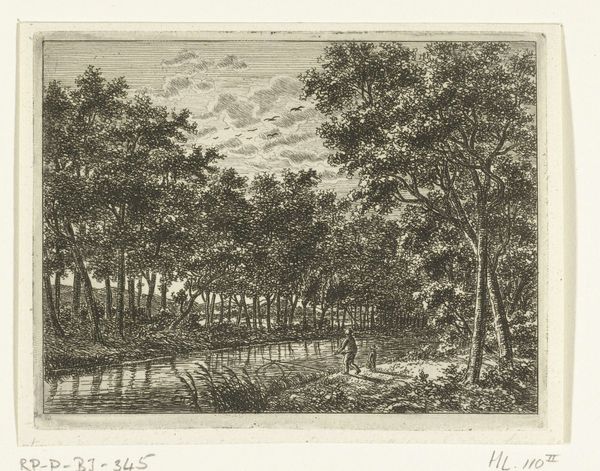

print, etching

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

etching

#

romanticism

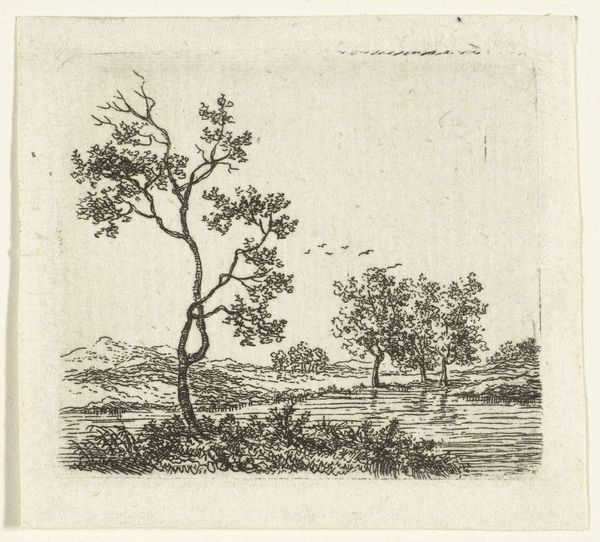

Dimensions: height 86 mm, width 117 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This etching, "Landscape with a Hunter Shooting Wild Ducks," attributed to Ernst Willem Jan Bagelaar, dates from 1798 to 1837. I’m struck by how meticulously crafted the image is. Editor: My first impression is that of tranquility, even with the hunter present. The monochromatic palette and delicate linework contribute to a dreamlike atmosphere, but there's also something about it that speaks to class divides and land ownership. Curator: Absolutely. As a print, it’s inherently tied to reproducibility and distribution. We should consider how Bagelaar's etching democratized access to landscape imagery. Etchings involved labor-intensive processes of metalworking, acid-etching, and careful inking – craft traditions meeting nascent industrial methods. This scene, depicting the act of hunting, likely served a specific, bourgeois clientele, eager to flaunt an engagement in the realm of the rural. Editor: Precisely. While seemingly pastoral, the hunter represents an imposition of order. Hunting scenes have a deep-rooted association with power. Consider the mythologies—Diana, Actaeon—the archetype speaks of pursuit, desire, even transgression. And those ducks in the water, so unaware... It’s a representation of dominance over the natural world. Note how the trees, though realistically rendered, frame the landscape in a way that guides our gaze directly to that central scene of implied violence. It also prompts a reading of class dynamics and the landed gentry in a period of growing capitalist production. Curator: That makes me think about the commercial exchange surrounding such prints. Who owned these images, what spaces did they inhabit? Bagelaar's technical skill in translating the landscape into this medium highlights a system of production – paper, ink, the press – that fueled the circulation of ideas about nature and ownership. Did this process serve to further entrench class structures? Editor: It undoubtedly codified existing beliefs while perhaps creating new visual languages around ownership. Looking beyond the immediate imagery, one has to ask what purpose those faint figures in the background might serve, barely hinted in the distance? Their inclusion lends scale to the land, perhaps subtly reinforcing notions of space and place. And beyond that – do you perceive a premonition of ecological crisis foreshadowed in the print’s seemingly serene panorama? The symbolic interplay can take several interpretations, of course, given Romanticism's obsession with symbols. Curator: It's striking how our readings diverge yet inform one another. Your iconographic approach draws attention to the symbolic charge of the imagery, while my materialist lens grounds us in the economic and social relations embedded in its production and distribution. Editor: A truly enlightening exchange. Thank you. Curator: Likewise. A revealing glimpse indeed into this landscape and its latent stories.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.