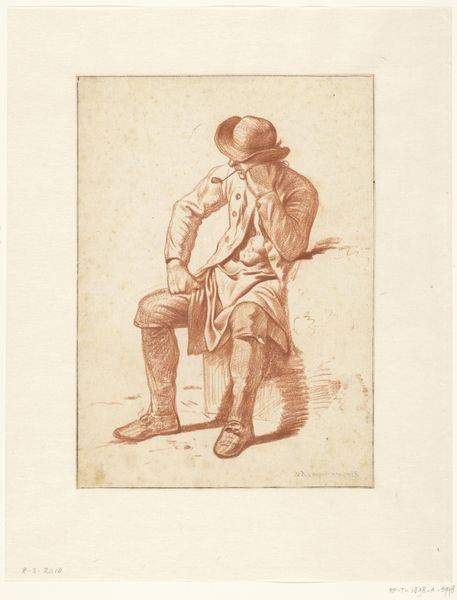

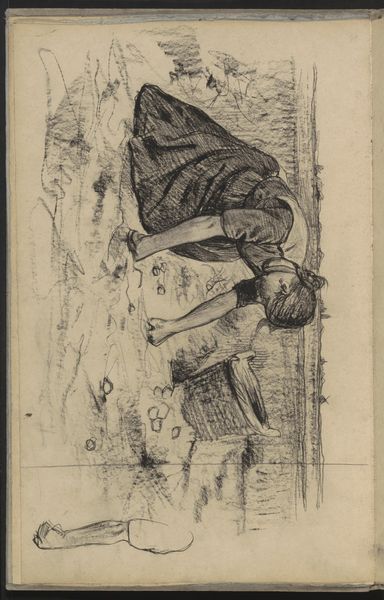

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

pencil drawing

#

romanticism

#

pencil

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 173 mm, width 151 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

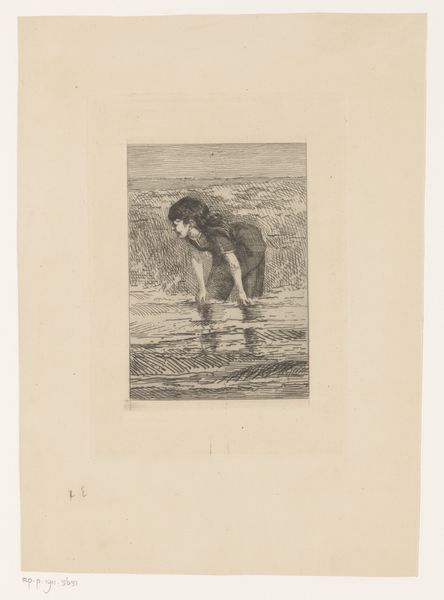

Curator: At first glance, there’s a real somberness to this work; the light is grey and the figure is bent, engaged in a back-breaking task. Editor: That's Wouter Johannes van Troostwijk’s “Kneeling Man Scooping Water with a Jug,” created around 1807. It’s a pencil drawing held here at the Rijksmuseum. Curator: Pencil—there’s something almost humble about choosing that medium. You're dealing with raw graphite, transformed only by pressure and skill. It makes you consider the accessibility of artmaking at this time, perhaps. Were drawings like this often made as preparatory sketches, or considered finished works in their own right? Editor: Often, yes. And remember, the period coincided with significant social upheaval, impacting the art world too. Public art institutions were only just emerging. An artist like Troostwijk, showing everyday labor, democratized art's subject matter in a way, bringing common scenes into a domain usually reserved for elites or biblical allegories. Curator: Right, the composition itself also guides how we interact with this scene. Notice how low we’re positioned, mimicking the figure's perspective. We’re brought into the act of collecting water, physically grounded and immersed in the reality of manual labor. Is it idealizing or observing? Editor: I see a depiction of a crucial economic activity, yet the somewhat melancholy tones suggest how that intersects with an emergent Romantic aesthetic that's shaping the social imagination. What looks at first to be simple documentation takes on a layered meaning depending on the viewers social circumstances, and how their tastes were informed through the popular prints and exhibition cultures developing in that era. Curator: So even the choice of seemingly basic materials, like the pencil, engages in complex discussions around production, artistic intentions, and broader access to the art world during the early 19th century? Editor: Precisely. I think this work helps reveal some subtle negotiations around social hierarchy, aesthetics, and value systems that are worth excavating further. Curator: Thank you, those points really highlighted dimensions that add layers of richness. Editor: My pleasure. I see him every day.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.