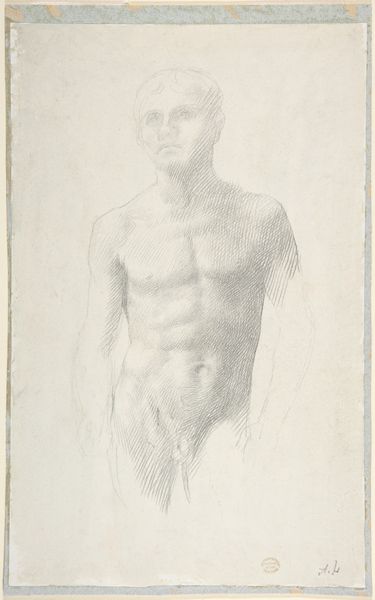

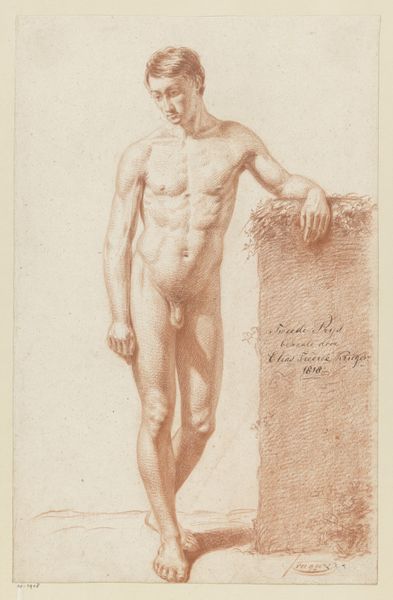

drawing, pencil, graphite

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

graphite

#

portrait drawing

#

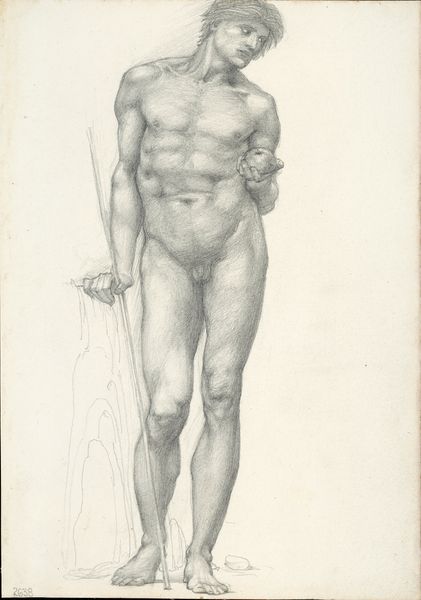

academic-art

#

nude

#

realism

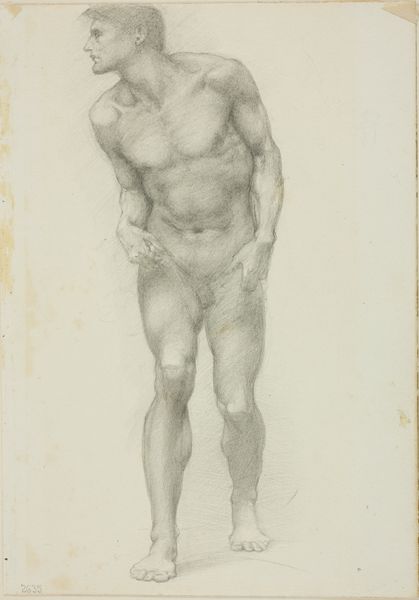

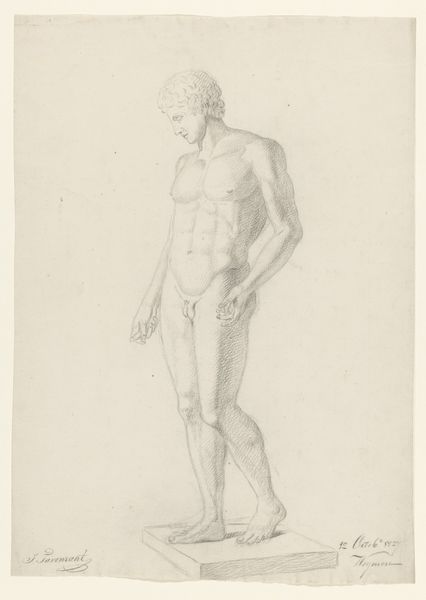

Dimensions: height 476 mm, width 302 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

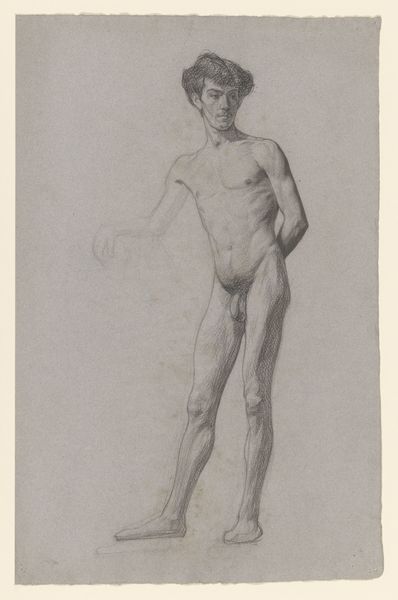

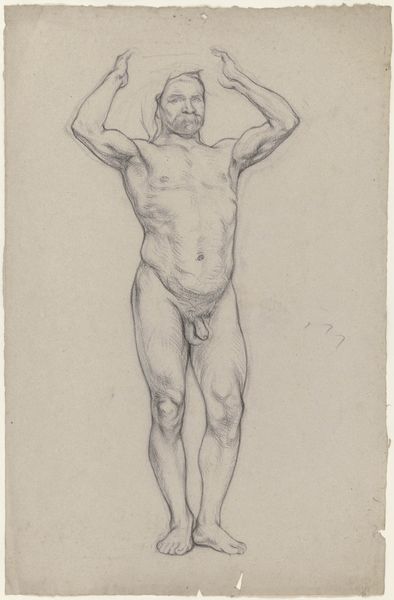

Curator: We're standing before "Standing Male Nude, Front View," a pencil and graphite drawing attributed to Jan Veth, created sometime between 1874 and 1925, now residing in the Rijksmuseum collection. Editor: It's surprisingly gentle, isn't it? Considering the subject. There’s a certain vulnerability conveyed through the soft lines and shading. He isn't posed in a particularly heroic or overtly sexual way. Curator: The drawing is clearly situated within the academic art tradition of the period. Nude studies, particularly male nudes, were essential to the training of artists within that system. Think about the power dynamics inherent in the gaze—who is allowed to look, and at whom? These depictions often served to reinforce established social hierarchies, especially around masculinity. Editor: Absolutely, but I also see hints of challenging those hierarchies. Look at the man's face. He's not idealized; he possesses a strong, perhaps even weary, expression. There's a palpable sense of humanism here, defying the often detached observation found in strictly academic studies. Is there a tension perhaps between representation and a search for something more real, or more genuine about the male form outside a framework of power. Curator: I see that tension playing out particularly in the incompleteness of the rendering. The background is nonexistent, throwing focus on the man and away from a possible social setting. Is it an avoidance of grounding that form in cultural power? Is that then a choice that removes a historical reading? What statement might Veth have been making about the male figure by leaving him somewhat suspended in time? Editor: He’s an individual divorced from a broader narrative that allows one to explore issues of identity beyond prevailing orthodoxies. Consider the impact this kind of representation could have had, particularly in challenging traditional, often highly restricted, portrayals of the body and its representation in the 19th century. Curator: Thinking about art history is very helpful as it gives the means to reflect upon a drawing in a different way, and to question what its artistic process meant within those changing values, even, or maybe, in a silent drawing. Editor: And for me it helps consider what is not there so that one might focus not only on technique and form but its enduring questions around personhood and cultural influence, then and now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.