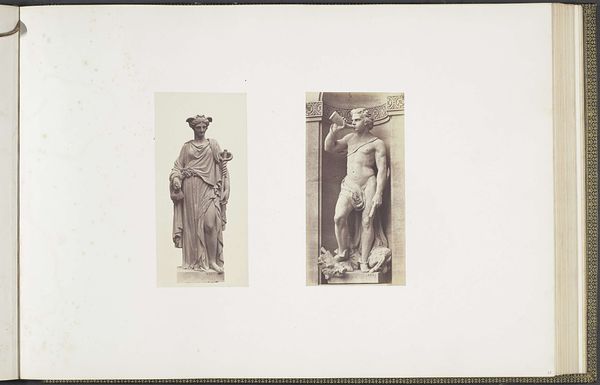

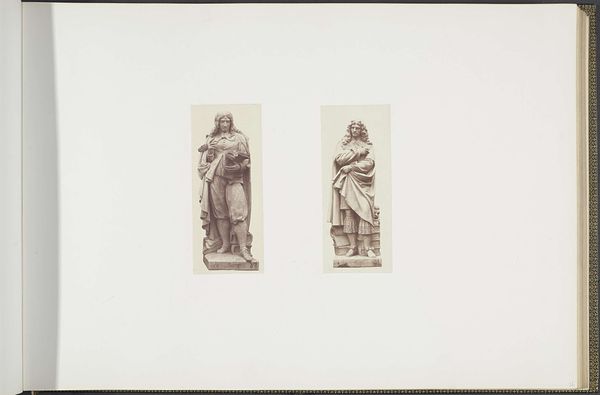

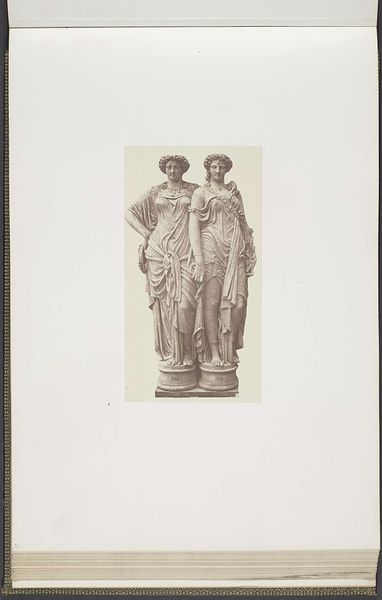

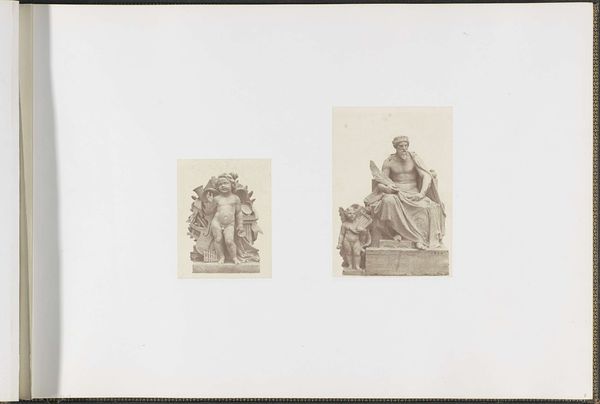

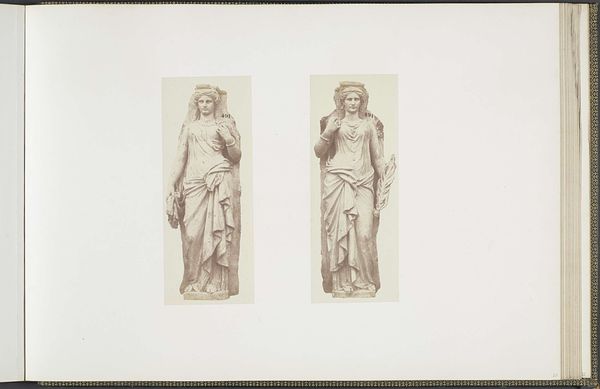

Gipsmodellen voor beeldhouwwerken op het Palais du Louvre: links "La Pêche fluviale" door Jean Jules Allasseur en rechts "Le Berger" door Jehan Duseigneur c. 1855 - 1857

0:00

0:00

edouardbaldus

Rijksmuseum

photography, sculpture, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

neoclacissism

#

figuration

#

photography

#

sculpture

#

history-painting

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 378 mm, width 556 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This photograph, taken by Edouard Baldus around 1855-1857, shows plaster models for sculptures on the Palais du Louvre. The titles are quite literal: "La Pêche fluviale" and "Le Berger", or "River Fishing" and "The Shepherd." They strike me as incredibly serene and poised, a real throwback to classical ideals. What resonates with you when you look at this image? Curator: The photograph, while depicting neo-classical sculptures, captures a moment of transition. Neoclassicism was a conscious return to the artistic values of antiquity, emphasizing reason, order, and idealized forms. But here, Baldus presents us not with the final marble object, but the plaster model, a sort of liminal stage, an ephemeral stand-in, charged with potent cultural symbolism: consider the shepherd, staff in hand, evoking pastoral ideals – simplicity, closeness to nature, perhaps even a subtle religious undertone through the symbol of the Good Shepherd. How does that symbolism play out in our modern visual language? Editor: So, the plaster hints at a process, a transition... interesting! The figures themselves feel familiar, like echoes of ancient Greek or Roman statues. The woman has what looks like an oar, or maybe a rudder, alongside her... Curator: Indeed. The river represents the flow of life, while the fishing is, in the most direct interpretation, to benefit from the river, or rather the occasion; to use the life flow at your advantage and make profit from it. But there is more to it, do these Neoclassical symbols speak directly to our own world, or have they been altered and re-purposed through cultural drift? Editor: I guess it makes me think about how we continue to borrow from the past, recycling and reimagining old stories and figures. I never thought about plaster having any significance before. Curator: Exactly! It reminds us that images are not static. Their meanings shift and deepen as cultures evolve and interact. The visual symbols act as a historical fingerprint of those complex adaptations of meanings in real-time. Editor: This has totally changed my view; it's amazing how a photograph of a plaster cast can reveal so much about cultural memory. Curator: Precisely. By focusing on the language of symbols, the memory continues, even after the stone and plaster start to crack.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.