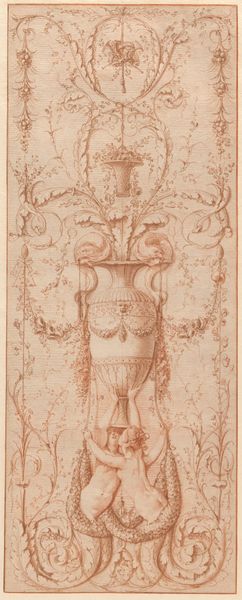

drawing, print, watercolor

#

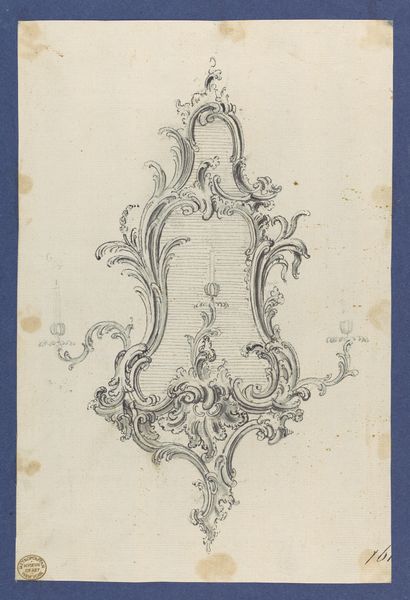

drawing

#

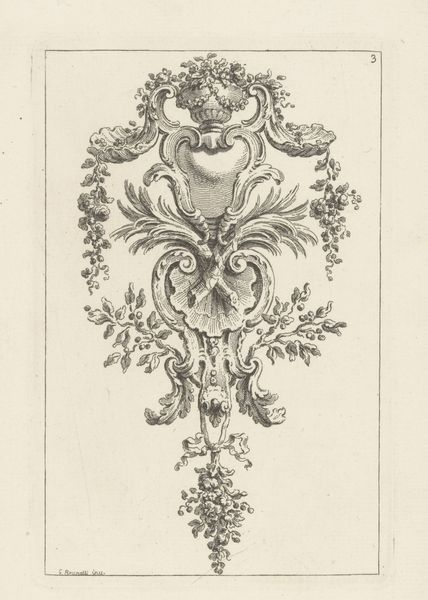

baroque

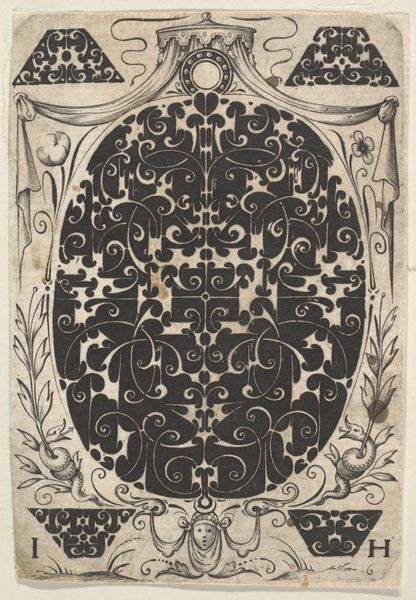

# print

#

form

#

watercolor

#

watercolour illustration

#

decorative-art

#

watercolor

Dimensions: 16-5/8 x 12-3/8 in. (42.3 x 31.4 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

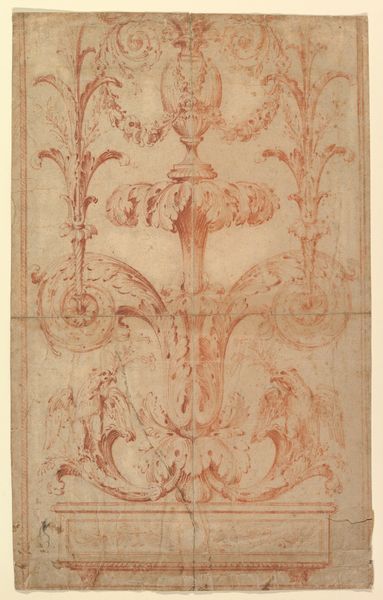

Curator: Here we have "Design for a Cartouche," a watercolor and ink drawing likely created sometime between 1700 and 1800 by an anonymous artist. The work resides here at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: It’s really quite elegant, isn’t it? I am struck by the delicate palette—those soft pinks against the muted yellow evoke a sense of refined gentility, but I have to wonder about what kind of patron or institution might require this design? Curator: Indeed, it screams opulence. Cartouches, historically, served as frames for inscriptions, coats of arms, or other symbolic devices, common in architecture and decorative arts, to signify status or lineage. Looking at the piece from a purely formal point of view, one might interpret the swirling shapes as a product of its Baroque period, echoing the theatrical aesthetic impulses of European courts at the time. Editor: The design does scream class, privilege, and wealth! One immediately envisions this adorning the façade of a nobleman’s manor house. But what about the function? I feel these weren’t always harmless decorations. In our contemporary world, cartouches become problematic when associated with historical injustices, like aristocracy, or inherited privilege, serving as visible reminders of unequal power dynamics. Curator: It is precisely that tension between beauty and underlying social structures that is vital to the study of art history. The history of visuality plays a large role in dictating culture, or subverting expectations to create culture in response to the traditional role that these signifiers have played. Consider this drawing—presumably a design for a three-dimensional object. Someone envisioned this object, found the design pleasing, had it crafted, and likely prominently displayed it. Editor: It gives one pause, certainly, thinking about what this type of work would symbolize in today’s day and age. I agree. Its importance lies in its power to evoke an almost visceral understanding of those social forces at play during that particular era of European history. Curator: Ultimately, I think the historical role that these artworks serve should always be called to question and examined! Editor: Agreed! Examining them is an inherently active step in reshaping our present and, thus, our future.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.