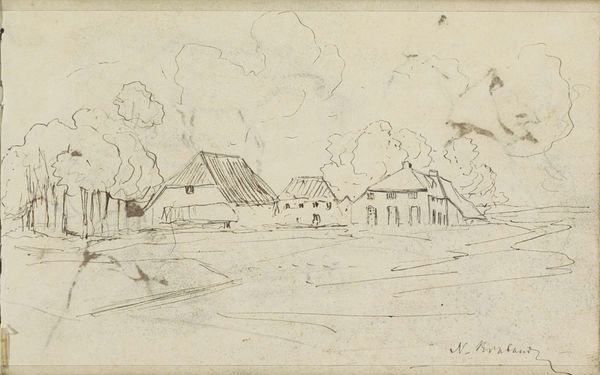

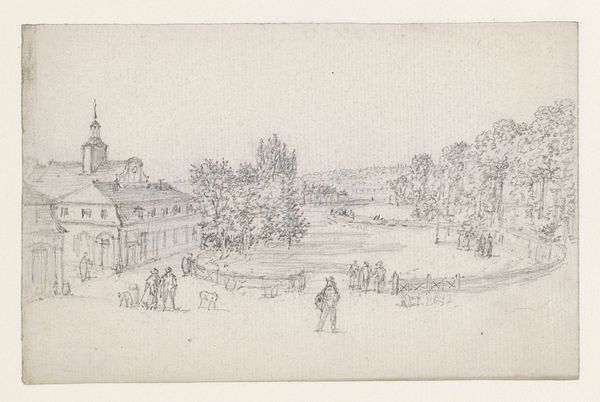

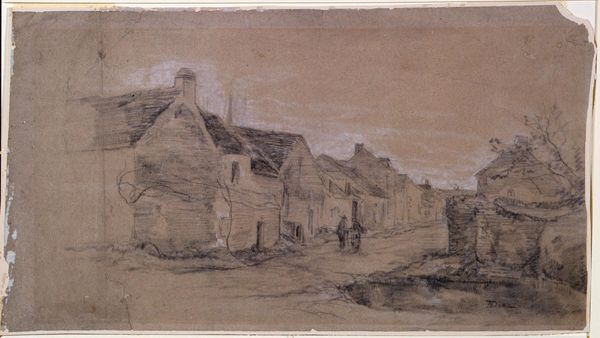

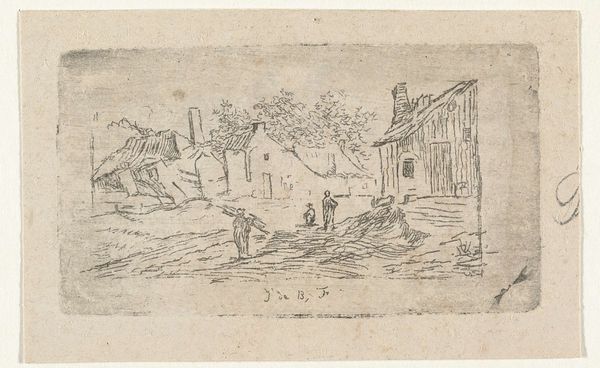

drawing, paper, ink, pencil

#

drawing

#

pen sketch

#

landscape

#

paper

#

road

#

ink

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

romanticism

#

pencil

#

horse

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

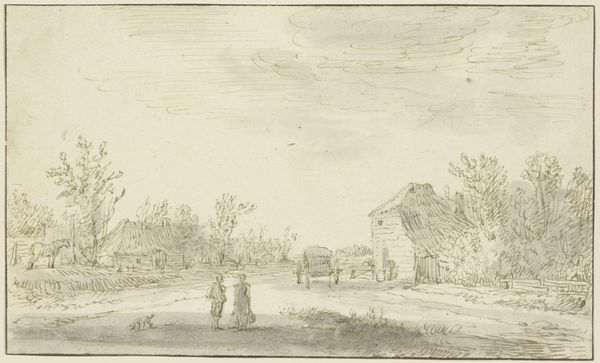

Editor: We’re looking at "Landweg in Kleef," a pen and ink drawing from 1839 by Johannes Tavenraat, currently housed at the Rijksmuseum. The scene feels like a quick snapshot, capturing a moment of everyday life. What draws your attention when you look at it? Curator: It’s interesting to consider this snapshot within the context of burgeoning industrialization. Here we see, ostensibly, a charming country road. But look closer; it is more than just a landscape. Tavenraat documents a society on the cusp of massive change. Who do you see represented, and perhaps more importantly, who *isn’t*? Editor: I see figures who look like travelers and townspeople…what looks like maybe merchants on the road... but are you suggesting that what's absent—the factories, the industrial workers—tells a story too? Curator: Precisely! Consider the rise of Romanticism at this time—an artistic movement often fueled by nostalgia for pre-industrial, agrarian societies. Tavenraat’s drawing, in its seemingly simple depiction of a “landweg” or country road, could be interpreted as a quiet commentary. Is it celebrating rural life, or is it a lament for something already fading away? Are we looking at a scene of social harmony or an idealized view obscuring deeper inequalities? Editor: I didn’t consider that the image might be actively choosing to leave something out. Curator: Exactly! Art often reflects the social and political anxieties of its time. Consider also the rise of Realism. Tavenraat toes the line between both artistic movements here. I think there's tension in those artistic and cultural positions. What do you think about the fact that most people in the drawing appear idle and perhaps poor? Editor: So, what seemed like a simple genre scene becomes a window into a complex negotiation of social and economic forces at play in 19th-century Netherlands. It certainly pushes us to ask what stories get told, and whose stories are left untold. Curator: And by acknowledging these contextual absences, we see the piece anew, informed by both the historical narrative it presents and the one it chooses to omit.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.