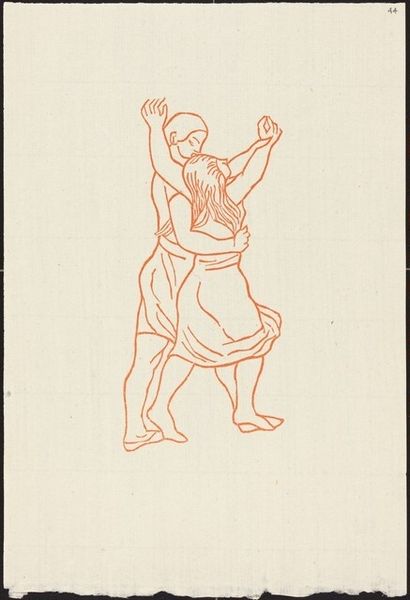

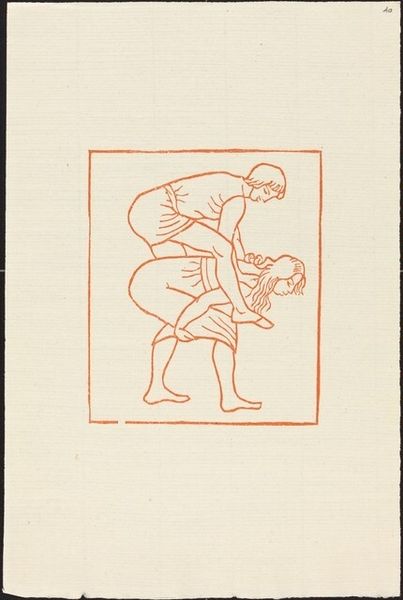

drawing, print, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

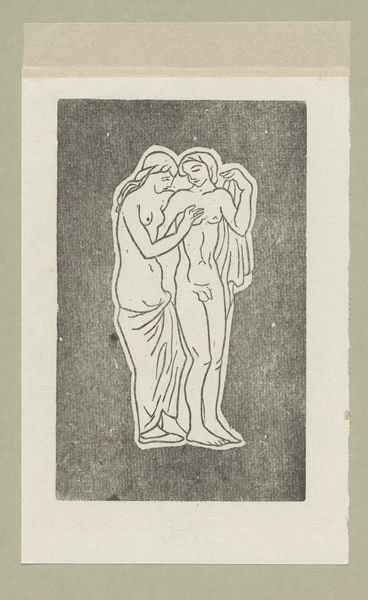

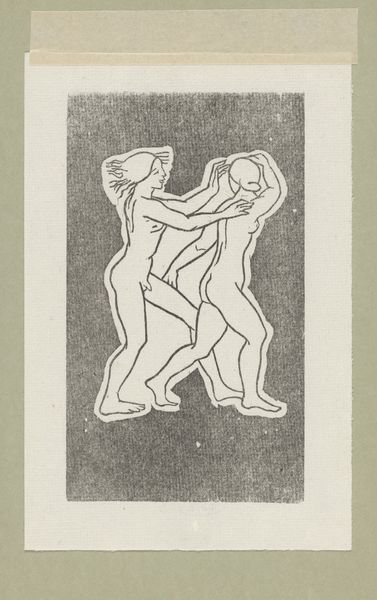

ink paper printed

# print

#

landscape

#

classical-realism

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

#

line

#

academic-art

Dimensions: height 138 mm, width 117 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

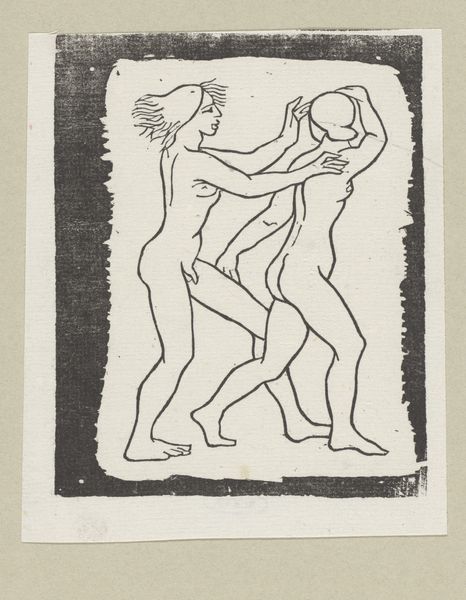

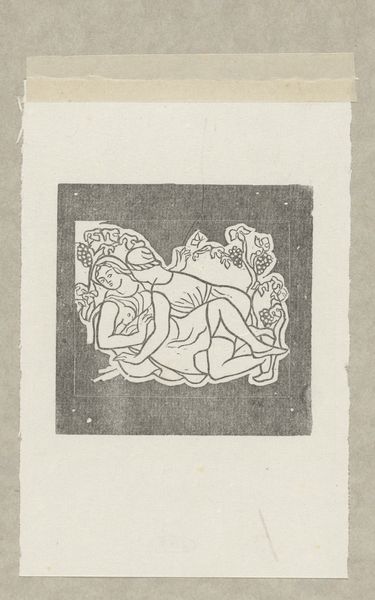

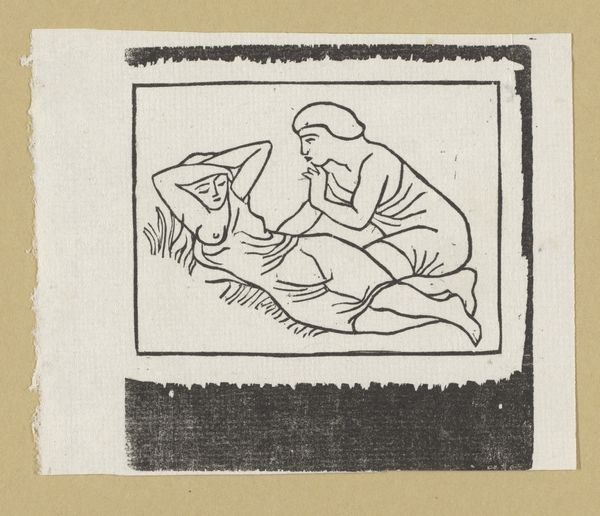

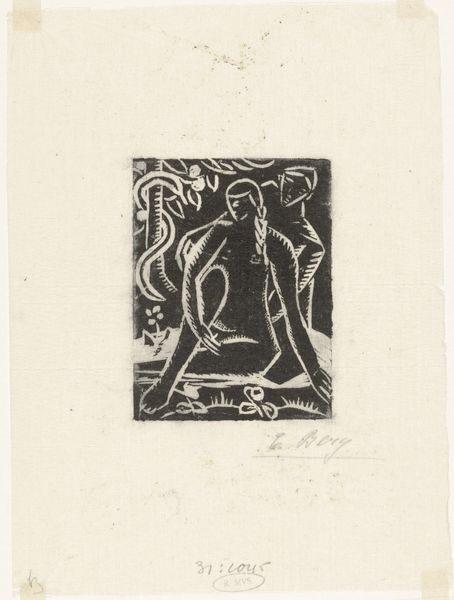

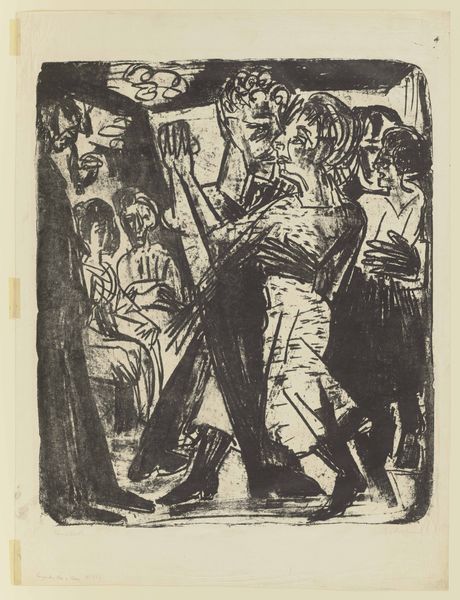

Curator: This fascinating print, residing here at the Rijksmuseum, is titled "Chloë abducted by the shepherd Lampis," realized by Aristide Maillol in 1937, employing ink on paper. My first impression? The linear simplicity is quite striking, bordering almost on abstraction. Art Historian: Yes, and note how this relatively late work taps into a very long tradition of pastoral imagery! It presents us with an Arcadian fantasy during a tumultuous period. You see echoes of classical antiquity filtered through early 20th-century sensibilities. Curator: Absolutely! Looking at it materially, I am compelled by the tension between the crispness of the figural lines and the rough, almost crudely textured blocks that form the background and surround. One sees it both as drawing, through its figures and a constructed printed object due to these rough edges. Art Historian: It’s important to remember the context in which Maillol operated. He wanted to recover a certain monumentality of form outside academic strictures. Think of the rise of Fascism and the nostalgia for classical ideals, co-opted and instrumentalized by authoritarian regimes, and contrast that with Maillol's simpler rendering, almost a plea for humanist values in perilous times. Curator: Interesting to consider his use of a print, rather than other methods such as sculpture that he was best known for. The reproductive quality of printmaking democratizes images, placing it outside conventional high art contexts. Was this meant for wide distribution or produced to make art more accessible? The story is about two classes that lived together as opposed to an image from high society. Art Historian: It invites speculation about viewership and audience engagement, definitely. Remember too, classical subjects weren’t simply aesthetic choices—they served as a visual language understood by a cultivated public, even as that public was changing rapidly in the early 20th century. This might be viewed today as art using history as material. Curator: Indeed. Reflecting on this image, it is fascinating to examine not just the romanticism of its subject, but also its physical means of production as a site of tension, both enhancing and undercutting that romance. Art Historian: Yes, it reminds me how much even seemingly idyllic images participate in the historical and political currents of their time, whether deliberately or unconsciously. It calls on the spectator to unravel those links.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.