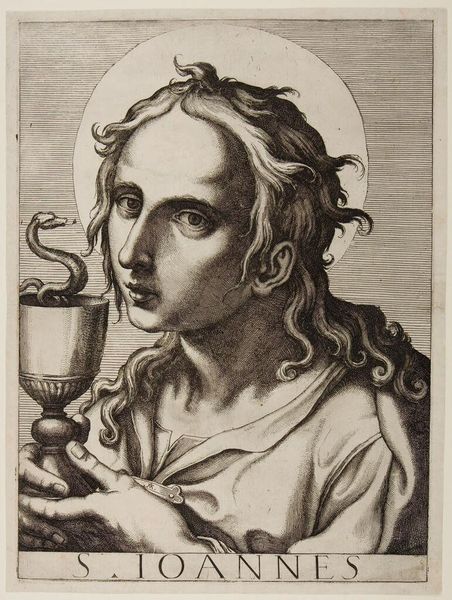

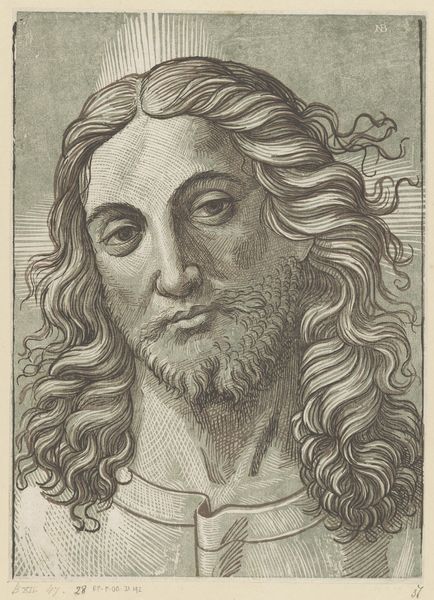

engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

caricature

#

pencil drawing

#

line

#

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 505 mm, width 374 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Raffaello Schiaminossi’s "Johannes de Evangelist," created around 1606-1607. It's an engraving, currently residing in the Rijksmuseum. I'm struck by the almost unsettling gaze and how sharply the lines define his features. What’s your take on it? Curator: This engraving gives us insight into the role of religious imagery in the early 17th century. Consider the cultural climate: the Counter-Reformation was in full swing. Schiaminossi, likely working within a specific patronage system, depicts John holding a chalice with a serpent—a reference to a legend where he detected and survived a poisoning attempt. The dramatic lighting and intense emotion, typical of the emerging Baroque style, served a powerful propagandistic function for the Catholic Church, reaffirming faith and divine protection. Editor: So, the engraving acted almost like a poster back then, solidifying religious belief? Curator: Exactly! Engravings were relatively easily reproduced, allowing for wider dissemination of religious narratives and, importantly, of the patron's desired interpretation. It invites the public to contemplate not just the saint’s story, but the Church’s power. Notice how the composition directs our attention to the chalice. Do you see how that draws viewers in? Editor: I do! It's subtle but clever. So, looking at it now, beyond just appreciating it as art, it represents the power dynamics of the time. Curator: Precisely. Understanding the social and political landscape provides a richer context. The image becomes a tool, and the artist, consciously or not, a participant in that power structure. Editor: I see it so differently now, understanding the historical background. Curator: That’s the beauty of historical perspective; it transforms our reading of art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.