Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

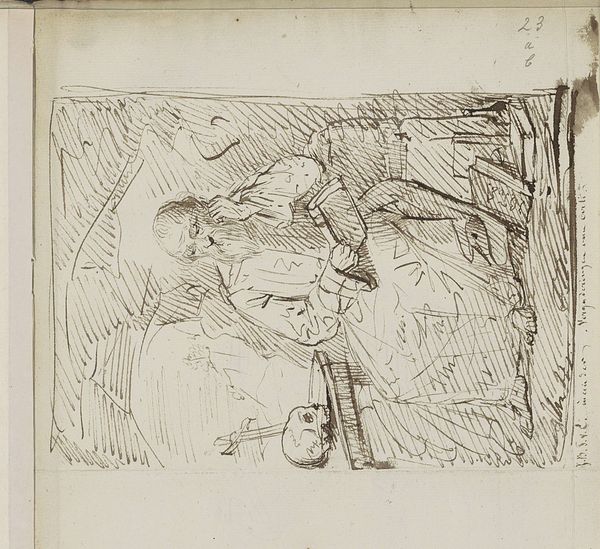

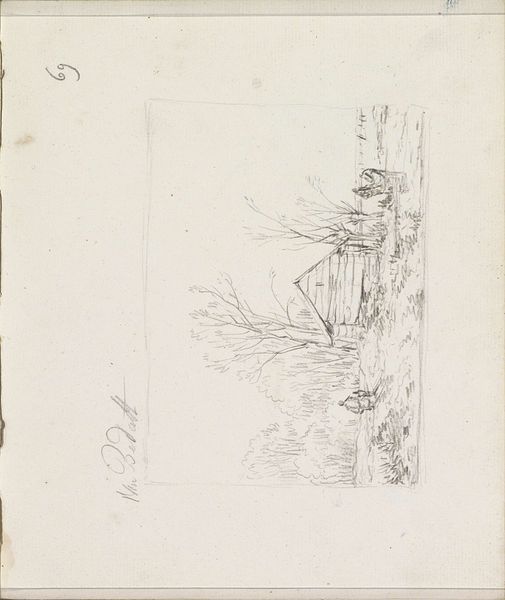

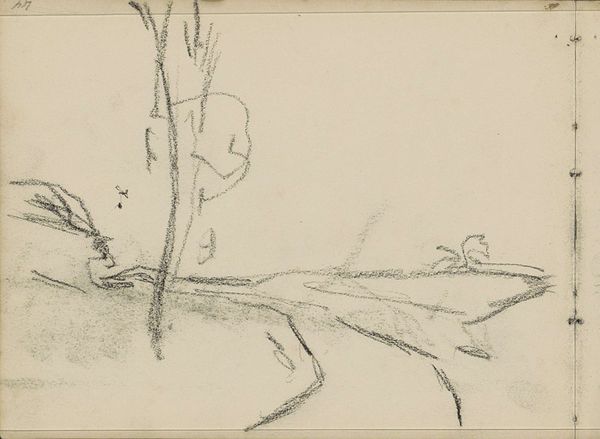

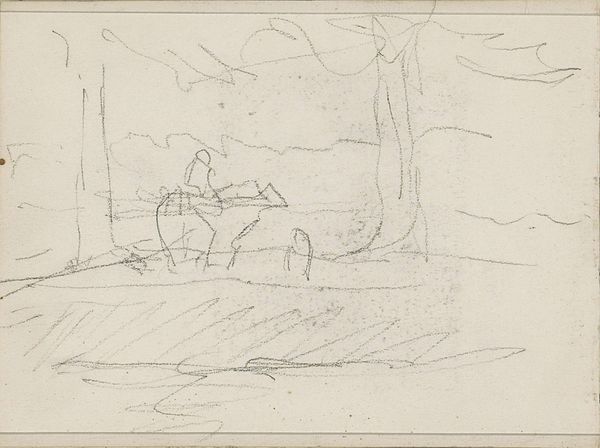

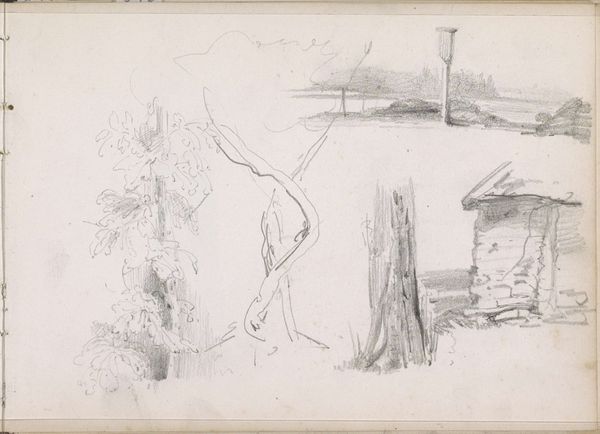

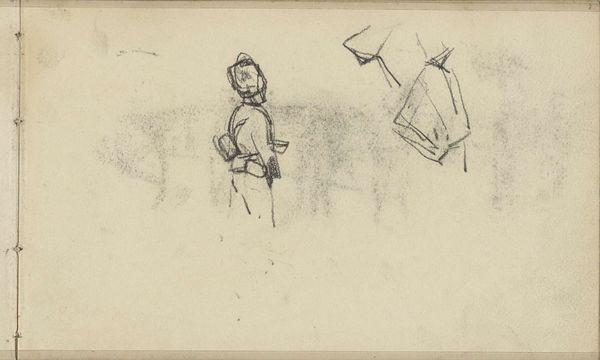

Editor: We're looking at "Ruiter bij een boom aan een waterkant," or "Horseman by a Tree at the Waterfront," by Anton Mauve, made sometime between 1848 and 1888. It's a pencil drawing housed here at the Rijksmuseum. It has a wonderfully rough quality; the landscape feels sketched in a fleeting moment. What stands out to you? Curator: I am intrigued by the interplay of form and space. The artist has defined the scene through a series of lines that prioritize shape, delineating the basic structure of the composition, its tonality. How does the application of line weight inform the perception of depth? Notice how the heavier lines define the foreground water, creating a contrast with the softer rendering of the background. Editor: That's a great point. It seems almost abstract in places. Does the sketch-like quality contribute to its artistic value? Curator: The sketch serves as a foundational exploration. Its merit is based not just in what it depicts, but in how those forms engage with and activate the two-dimensional space. In doing so, does the materiality of the support itself, that very paper, not come into greater prominence? Editor: That's fascinating; it is like seeing the artist's thought process. Curator: Precisely. What appears as unfinished is a concentrated study of form, light, and spatial relationships reduced to its essence. Through careful composition and economy of line, the artist brings forth a compelling narrative of place, of subject. Editor: I'm now looking at it in a completely different way. I was focused on what was represented, and now I see it's about how it's represented. Curator: Yes. It invites us to decode the structural language through which art communicates.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.