![[Two Chinese Men in Matching Traditional Dress] by Raimund von Stillfried](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzL2UwYjk0NGNiLTEyNWYtNDYyNy04OWRmLWIyMGRlYTM1NGI3Ny9lMGI5NDRjYi0xMjVmLTQ2MjctODlkZi1iMjBkZWEzNTRiNzdfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

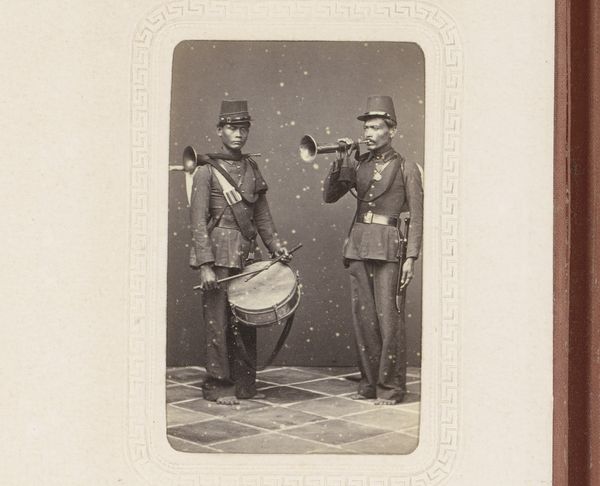

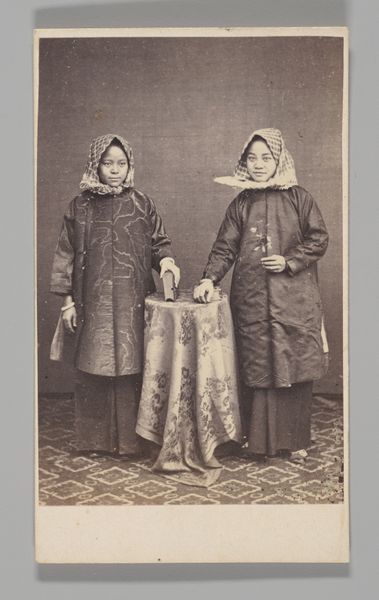

[Two Chinese Men in Matching Traditional Dress] 1870s

0:00

0:00

photography, collotype, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

16_19th-century

#

asian-art

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

historical fashion

#

collotype

#

orientalism

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

19th century

#

men

Dimensions: 23.6 x 19.3 cm (9 5/16 x 7 5/8 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This photograph, entitled "[Two Chinese Men in Matching Traditional Dress]," was taken in the 1870s by Raimund von Stillfried. It’s a gelatin-silver print, later printed as a collotype, and resides here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The print is part of a larger series that depicts people from various regions, likely intended for a Western audience. What are your first impressions? Editor: It has a certain formality, yet something about their gaze feels vulnerable. Their matching outfits, almost like uniforms, create a sense of cultural identity, but their individual expressions hint at something more personal. I'm curious about the cultural context surrounding these garments and objects like the beads one figure is holding. Curator: Indeed, Stillfried capitalized on Western fascination with the “Orient” to produce and market these kinds of studio portraits. The setting is artificial and constructed, designed to satisfy the era's notions of Chinese culture. Their garments speak to the Qing dynasty's standardization, a deliberate move to consolidate power and project visual unity, perhaps meant to imply social cohesion and reinforce cultural hierarchy for outsiders. Editor: Those conical hats immediately bring to mind shamanistic or priestly associations; they're very striking. I'm also wondering about the red sashes. Is this an indicator of status? They break up the darker, heavier tones of the robes and catch the viewer’s eye, guiding us toward the figures’ center. The beads seem like rosaries, objects that would imbue one’s social status as a man of virtue, but also function as spiritual tools. Curator: Yes, the visual cues in these portraits were carefully chosen. Consider, though, how limited access Westerners would have had to accurately interpret such cultural codes at that time. The hats and robes were perhaps generically "Chinese" in the Western imagination, and so Stillfried used those symbols to fulfill commercial demands and exploit existing stereotypes. The question then becomes how we today should re-evaluate those stereotypes? Editor: It is problematic, certainly, but also presents an opportunity to reassess the symbolical depth. It forces me to consider not only the photographer's intent, but also what these figures might have hoped to convey, consciously or unconsciously. The image now stands at the crossroads of orientalist exploitation and invaluable historical record. Curator: Absolutely, and by examining photographs like these, we begin to understand the complex interplay between visual culture, historical narratives, and enduring power dynamics. Editor: I'm walking away with a renewed appreciation for how much an image can reveal—or conceal—depending on the context and perspective brought to it. The past and its meanings constantly evolve.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.