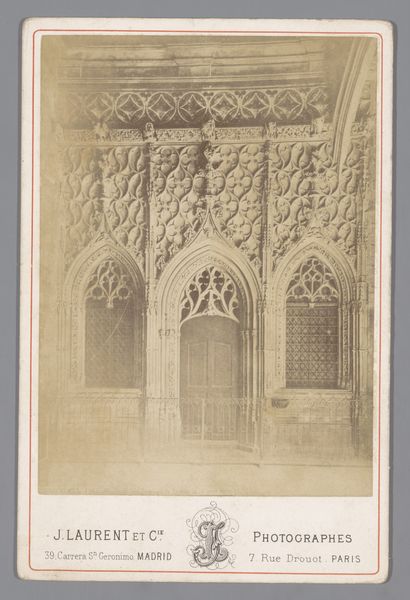

print, photography

#

medieval

# print

#

photography

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

Dimensions: height 165 mm, width 110 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

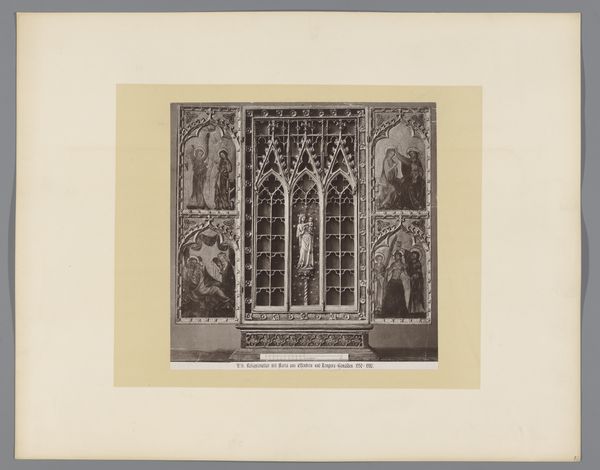

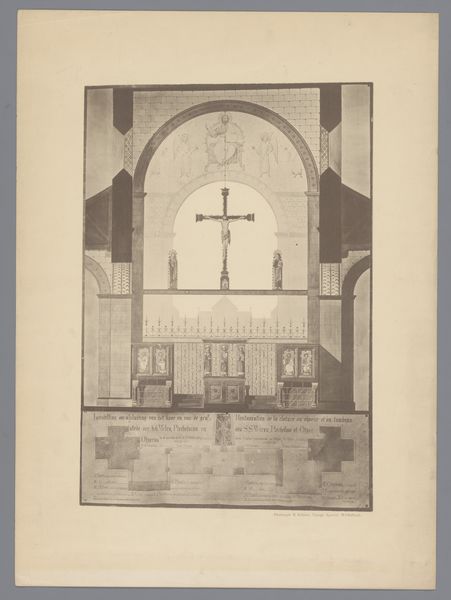

Curator: This is a photographic print by Léon & Lévy, capturing Hans Memling’s Shrine of St. Ursula. The image was likely created sometime between 1864 and 1900. What are your first impressions? Editor: It feels so formal, like a portrait, yet also strangely intimate. The detail, especially the Gothic tracery, almost overwhelms the scenes depicted on the reliquary itself. Curator: Precisely. I’m fascinated by how the shrine functions as both a sacred object and a historical record. It presents the legend of St. Ursula, but through a late 19th-century lens and production. Editor: Thinking about St. Ursula, and the story of a woman leading thousands of virgins, how might that legend speak to issues of female solidarity and autonomy through centuries? Is the narrative about collective female action or is there a different interpretation depending on what time period the legend is looked at from? Curator: I would say that it is crucial to contextualize it against a backdrop of medieval piety and gender dynamics. The representation, though religious, could embody the social and political climate in which women's collective identity or communal resistance has manifested, therefore sparking modern perspectives on this imagery, linking to the concept of feminine spaces of solidarity. Editor: And what of the individual figures within the panel scenes, their gestures and expressions? Do those carry different emotional weight in relation to their status? This image also brings in the idea of a collective martyrdom: the virgins are, as one, led, die, and achieve holiness as one group; it could also symbolize power in numbers or unified sacrifice. Curator: Absolutely. By dissecting such symbolism we’re acknowledging layered intersections between gender, power, faith, and politics. The historical context of a saint as an exemplar of collective death mirrors contemporary societal injustices that marginalized communities face through systemic oppressions of many groups treated as one faceless group or population to be taken care of through legislation. Editor: Indeed. Looking at the faces on the shrine, there's a universality there, an echo of archetypal expressions that transcends eras. It provokes consideration about human response to the big questions such as meaning, death, morality— and to questions such as female leadership and solidarity in historical times. Curator: A thought-provoking interplay of the specific and the universal, indeed, revealing just how potent a work of art can be, both historically and in the present.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.