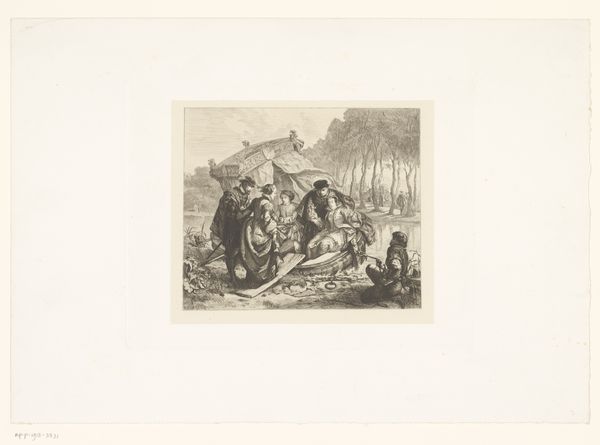

A Tavern in Normandy, from "L'Artiste" 1828 - 1893

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: Plate: 8 7/16 × 10 9/16 in. (21.5 × 26.8 cm) Sheet: 9 7/16 × 12 9/16 in. (23.9 × 31.9 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

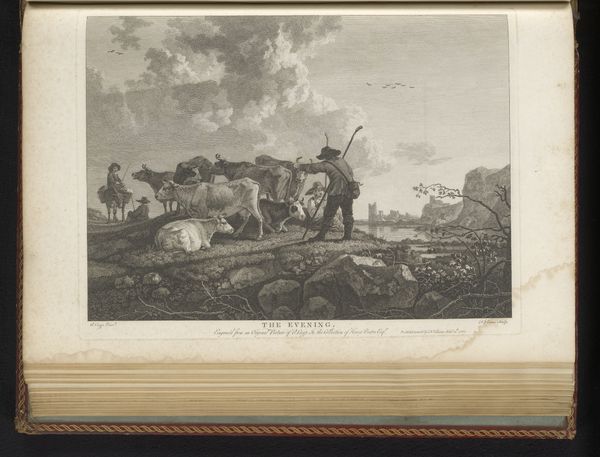

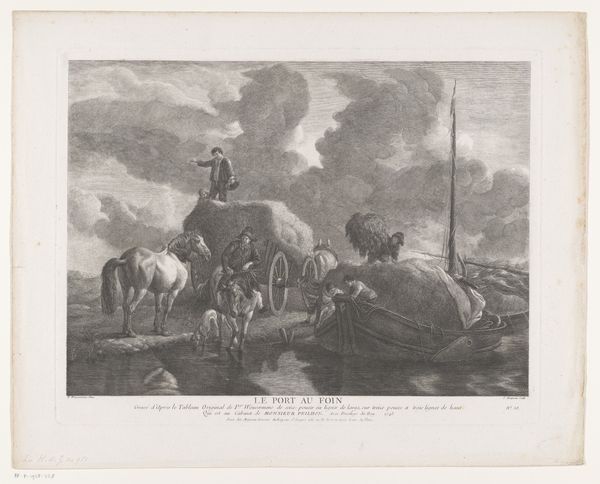

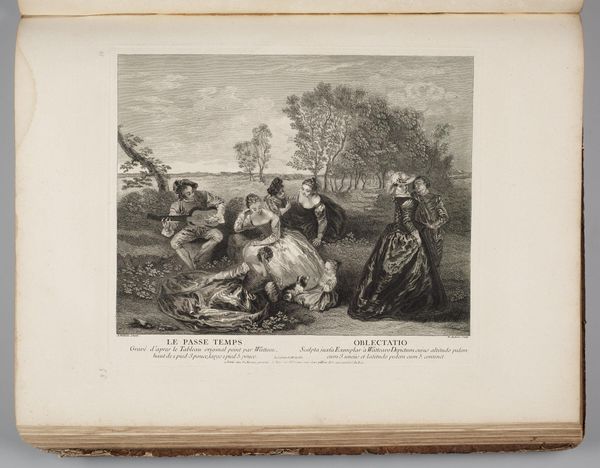

Editor: We’re looking at "A Tavern in Normandy" by Jules-Jacques Veyrassat, a print made sometime between 1828 and 1893. There's such a sense of everyday life in this scene; I'm immediately drawn to the juxtaposition between the men gathered at the tavern and the working donkey outside. How do you interpret this work? Curator: What strikes me is the intersection of labor and leisure depicted here. Consider the context: this is Normandy, a region with a complex history of agricultural and social struggle. This tavern becomes a focal point. But for whom? Notice the donkey, burdened, tethered to this space. Who is afforded the privilege of rest and revelry, and who remains bound to labor, even on the periphery? Editor: That’s a powerful point about who gets to participate in "leisure." So, you see the donkey almost as a symbol of those excluded from the tavern’s social circle? Curator: Exactly. And consider the rise of Romanticism during this period. Artists often romanticized rural life, but Veyrassat subtly complicates that narrative. He doesn't shy away from the inherent inequalities. The soft textures achieved in the printmaking underscore both the idyllic and the harsh realities of the setting. Do you notice anything about the light, and how it guides your eye? Editor: The light definitely draws attention to the figures inside, obscuring details. Maybe this represents a romanticised ideal as the hard toil is relegated to the edges of the picture. Curator: Precisely! What might appear as a quaint genre scene initially reveals itself, upon closer inspection, to be a commentary on the social fabric of 19th-century Normandy, raising questions about class, labor, and access. Editor: I never considered the donkey’s placement as a deliberate commentary. I was so focused on the interior scene. This gives me so much more to think about. Curator: And that’s the beauty of art, isn't it? It challenges us to look beyond the surface, question assumptions, and engage in critical dialogue with the past.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.