Copyright: Public domain

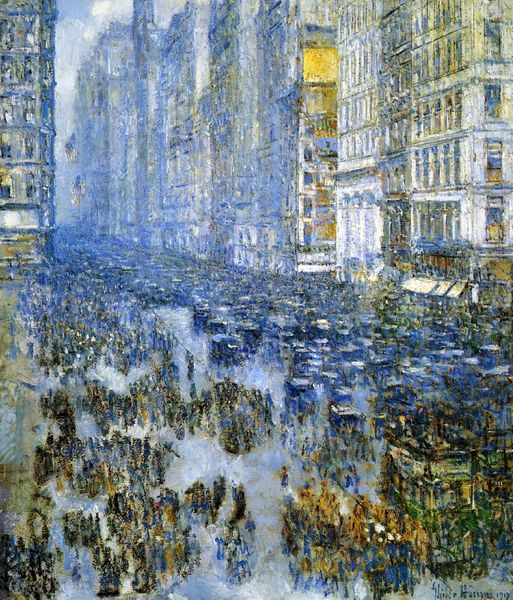

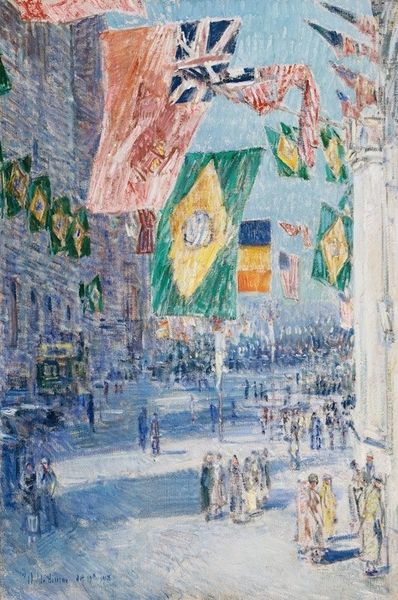

Curator: This is Childe Hassam’s “Up the Avenue from Thirty-Fourth Street,” painted in 1917. The canvas uses oil paint to render a lively New York street scene bedecked with flags. Editor: Wow, just pure exuberance! The colors kind of explode off the canvas. It's like a jazzy, patriotic confetti parade caught in a single, shimmering moment. Curator: The image is rich with contextual meaning. Painted during World War I, Hassam’s "Avenue" series often displayed Allied flags, a potent symbol of solidarity and patriotism within the sociopolitical landscape. The waving flags, particularly the prominence of the Allied nations like France, Italy and Great Britain, reflects a conscious effort to galvanize public sentiment toward intervention. Editor: Yeah, you feel that buzz, that feeling of everyone pulling in the same direction. It’s kind of romantic, right? Like everyone's heart is beating to the same rhythm. The blurred effect makes the crowd seem like a single, energetic being. Curator: But that energy, that shared purpose, can be viewed through a critical lens. In what ways did national unity serve particular political or economic interests during that period? Whose voices were amplified and whose were silenced under the banner of patriotism? This wasn't simply an outpouring of spontaneous emotion, but also a strategic deployment of nationalistic symbolism. Editor: Well, now I’m feeling like I’m harshing everyone’s buzz by staring at it. But you’re right. Art can make you feel and think deeply, at the same time! Curator: Exactly. Thinking about art requires feeling and thinking about how history, politics and personal emotion can be intertwined. Editor: Right. I might never look at a parade the same way again! Curator: Precisely. The complexities in an artwork are a portal for a greater understanding of both our present and the past.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.