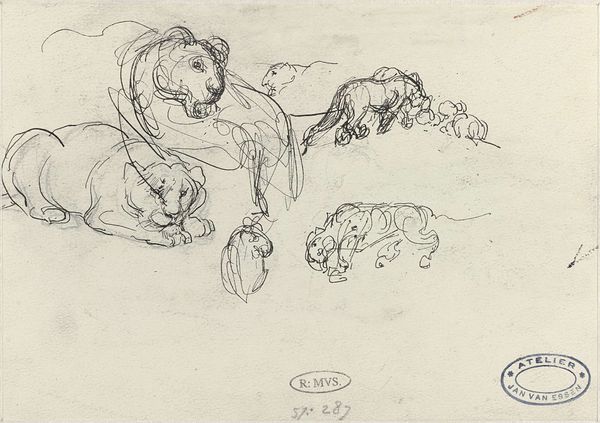

drawing, print, paper, ink, pen

#

drawing

#

ink drawing

#

animal

# print

#

pen illustration

#

pen sketch

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

#

line

#

pen

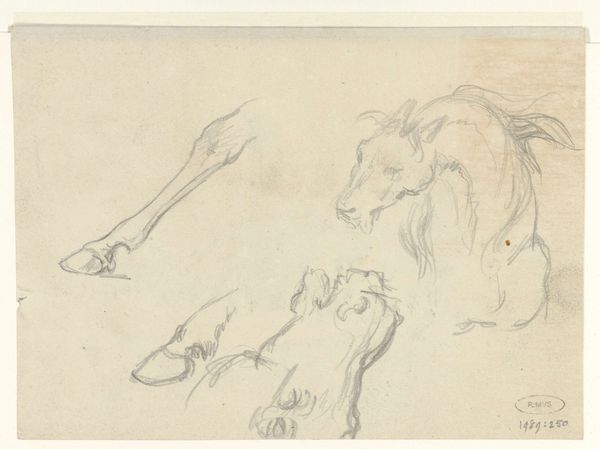

Dimensions: 219 × 308 mm

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: Here we have Sawrey Gilpin's "Three Lions," a pen and ink drawing of, well, three lions. It has a casual, almost sketchbook quality. What strikes me is how utilitarian the marks feel. What do you notice in terms of the materiality or social function of the drawing? Curator: Precisely. I see the stark lines, the quick strokes, and immediately consider the means of production. It wasn't meant, I suspect, for display in some aristocratic salon, but likely served as a preparatory sketch. Consider the type of paper; its rough quality suggests accessibility and low cost. Gilpin, by depicting animals – often associated with power and royalty – in such a casual medium, democratizes a traditionally elite subject. Editor: So you're saying the materials themselves speak to a wider audience? Curator: Yes. Ink, pen, paper – these were increasingly available thanks to the industrial revolution's expansion of material supply. This wasn't rare pigment painstakingly applied; this was about access and replication. Think of the printmaking processes of the time and how readily images could be circulated. Did this affect perceptions of animals and the accessibility of art? Editor: Interesting. The "original" artwork wasn't really the point; rather it was about its dispersal in popular culture? So, less "art" object and more "art" as readily produced material? Curator: Exactly! The "Three Lions" points toward the deconstruction of art's exclusivity and, conversely, speaks about consumption in that period. Editor: I had not considered the effect of the rise of material production on subject matter itself, very insightful! Curator: The key is to view these objects not in isolation, but within their dynamic networks of creation, distribution, and reception. That’s how we give a voice to a work that history tends to treat as voiceless.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.