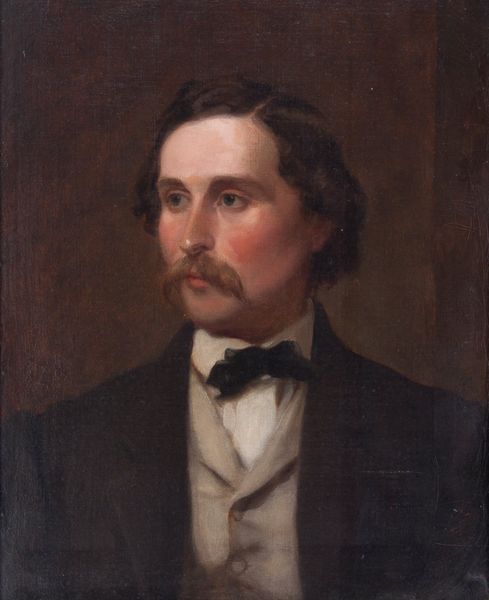

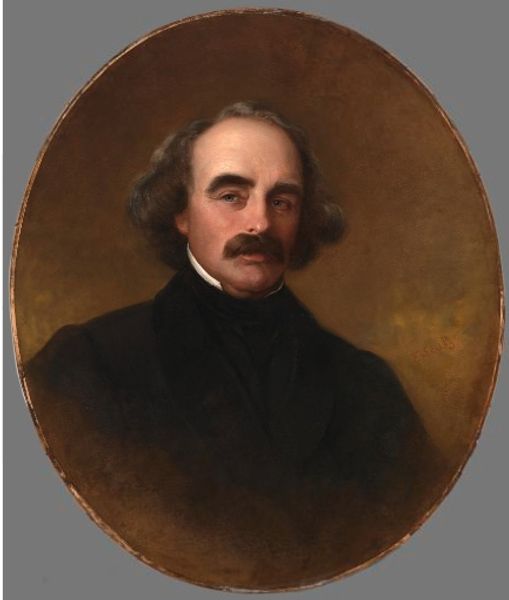

painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

portrait

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

romanticism

Dimensions: overall: 77.2 x 64 cm (30 3/8 x 25 3/16 in.) framed: 96.5 x 83.8 x 7 cm (38 x 33 x 2 3/4 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Here we have Charles Loring Elliott’s portrait of William Sidney Mount, likely created around 1850 using oil paints. What strikes you initially about this painting? Editor: Well, the color palette is certainly something. That fiery red vest against the muted background creates a visual tension; almost like a symbolic assertion of inner passion, even if it's within the confines of conventional portraiture. There is also the confident tilt of the head combined with what looks like the tools of his craft just there at the side. This speaks to a particular type of creative power that has been accessible for privileged white men in the mid 19th century. Curator: That’s interesting. Social context is crucial, of course. This painting fits into a broader narrative of artistic representation during the Romantic era, specifically in America. The emerging national identity very much shaped the subjects artists chose and how they portrayed them. It's less about aristocratic lineage and more about representing American ingenuity. Mount was a genre painter, depicting everyday life. Editor: Exactly. I would imagine that at this time Mount, as an artist of working class scenes, was likely engaged in his own, complex performance of masculinity. Considering the cultural and economic power attached to this performance, I can not ignore the way that men like him often occupied space and dictated social discourse in that time. This informs the portrait for me, even beyond Elliott's rendering. Curator: That reading makes a great deal of sense when you bring in his status as an artist. These portrait commissions are often about constructing legacies, building a reputation for an artist in the social arena as much as showcasing skill. It’s intriguing how Elliott captures Mount’s thoughtful gaze and artistic bearing here; the whole construction serves to legitimise both artists. Editor: The gaze is central, I agree. His is not passive. But given the limited possibilities afforded to, say, Black or female artists during that same period, it forces us to interrogate concepts like the artist gaze. Who has the 'right' to look, and who has the authority to depict? Elliott's portrait of Mount inadvertently becomes part of this complex social dialogue on privilege and representation. Curator: That really provides us with the nuance required. Thank you, it enriches my reading of the artwork so much more, situating it perfectly. Editor: My pleasure. Context truly is key.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.