drawing, print, pencil

#

drawing

# print

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

Dimensions: 9 1/2 x 6 13/16in. (24.1 x 17.3cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

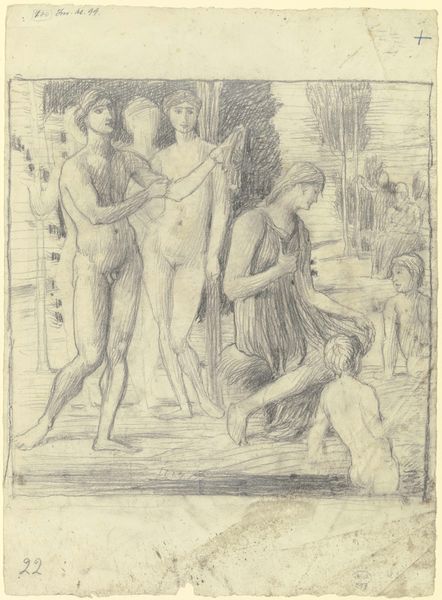

Curator: This is "The Baptism of Christ," a drawing likely made sometime between 1500 and 1600, attributed to Guglielmo Caccia, also known as Moncalvo. It is currently held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: My first impression is one of preparatory sketch – the figures are lightly rendered in pencil and charcoal, suggesting an artist working out the composition and details for a larger work. There's a real rawness in the depiction of the human form here. Curator: Absolutely. Think of the social implications of such a commission at the time. The Renaissance was experiencing seismic shifts in thought and devotion and we are only decades from the height of the Reformation and the beginnings of the Counter-Reformation that would follow. These theological arguments play out in the commission and re-telling of these stories. Editor: I'm intrigued by the use of charcoal and pencil together. It’s an interesting combination of materials. One adds depth, almost like a sculptural element defining musculature while the other provides for fine outlines. It gives a dynamic quality, highlighting the bodies as sites of production, labor, and their own mortality. Curator: Consider how the performative nature of baptism interacts with the Renaissance’s humanistic rediscovery of the individual. It marks Christ as human before his divine nature is revealed. This transition carries tremendous weight for all figures who see themselves in this historical moment. Editor: And it’s all conveyed so economically. I mean, look at the Baptist’s robe, its mere suggestion, compared to Christ’s exposed flesh. The artist prioritized that moment of transformation. The drawing speaks to a wider economic framework related to paper use, pigment access and ultimately the final destination of the work itself and the economy around religion during that era. Curator: Right. The rendering allows for emotional expressiveness, making it a compelling depiction. Even in its preparatory state, it encapsulates the intensity of that singular moment in religious history—the point of baptism marking both an ending and a new beginning, which is both personal and, simultaneously, politically and historically charged. Editor: It really does encourage you to think about the labour and intentionality behind it all and how even a sketch has something powerful to convey beyond the finished masterpiece.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.