drawing, ink, pen

#

drawing

#

allegory

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

ink

#

romanticism

#

pen

#

history-painting

Dimensions: 16 x 22 1/8 in. (40.64 x 56.2 cm) (sheet)23 5/8 × 29 5/8 in. (60.01 × 75.25 cm) (outer frame)

Copyright: Public Domain

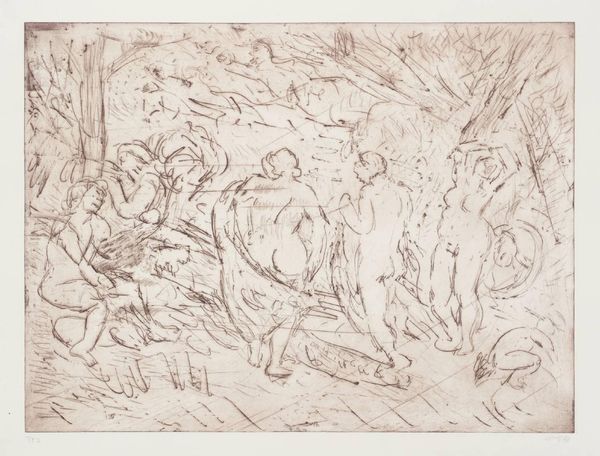

Curator: This ink and pen drawing, housed here at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, captures a pivotal moment from Greek mythology. Drawn circa 1800-1805 by Pietro Fancelli, it’s entitled "Orpheus and Eurydice in Hades (recto)." Editor: It hits you immediately, doesn't it? This kind of fever dream energy, with figures dissolving into each other. There’s a real rawness to it, even in its unfinished quality. You almost feel the desperation, the weight of that infamous backward glance. Curator: Exactly! Fancelli really evokes Romanticism’s obsession with the sublime and the darker side of human emotion. History painting and allegory often worked together like this. This moment in the myth highlights love, loss, and the limits of human agency. The placement of the figures, too, reflects how the narrative of this piece unfolds, even in that landscape that is incorporated. Editor: You can see that Orpheus is nearly lunging forward, a desperate plea frozen in mid-motion, whereas Eurydice is just fading away, not quite solid, barely there, even, amid that whirlwind of chaotic ink. The faces are especially affecting; there is such great storytelling at work with such minimal form. Curator: The institutional context of Fancelli’s practice is also important. Drawings like this, intended for a cultivated, aristocratic audience, were themselves luxury goods. It's interesting how the art world was structured by elites and academics. Fancelli shows how that kind of imagery can convey universal human themes like grief or unfulfilled longing. Editor: Absolutely, there’s that timelessness, that immediate access, no matter the specific social setting for its original creation. You don’t need to be steeped in art history to feel that loss resonating here. And isn't that the magic trick of art, really, making the grand myths personal? Curator: Ultimately, the drama conveyed by Fancelli really provides insight into the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Its concern for emotion as history shapes how we continue to interpret it as history today. Editor: And for me? It remains a deeply personal statement about the fragility of what we hold dear and our capacity for, perhaps, spectacularly human mistakes.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

Dense and rapidly executed, this drawing shows an artist freely exploring a subject for his own creative purposes. In this story from classical mythology, the poet and musician Orpheus attempts to rescue his bride, Eurydice, from the underworld. Journeying down into Hades he secures her release through the power of his music. But Pluto imposes a condition: Orpheus cannot look back at her until the two have emerged into the upper world. Fancelli depicted the fateful moment when Orpheus turns to look. As he grasps at her, Eurydice is pulled back into the depths. In Fancelli’s telling, the story is as much about the underworld as the couple. Pluto and Persephone are shown seated in a circular throne, reigning from above; Cerberus, the three-headed guard dog, snarls at Orpheus’s feet; and the three Fates, at left, measure out the thread of life with chilling indifference. A group of anguished figures crowded together in the sky may represent the region where the wicked are punished. A few have labels identifying the source of their misery: odio (hatred), vendetta (revenge), avarizia (greed). Fantastic airborne creatures—a long-beaked serpent, spiteful harpies, and a small fire-breathing dragon—torment the sinners.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.