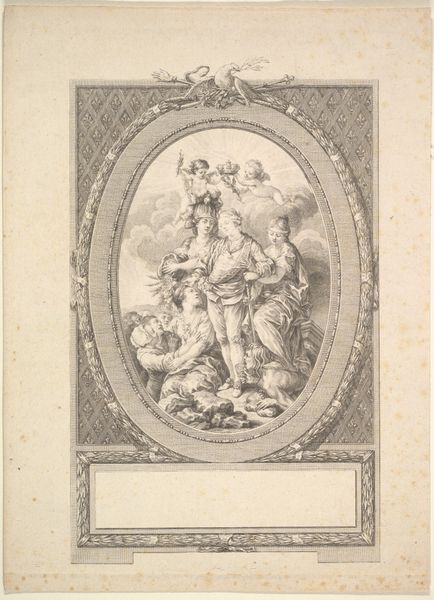

Cosimo III befæster Livornos havn. Tegnet forlæg til sølvplade, en af de såkaldte "piatti di S. Giovanni" 1702 - 1706

0:00

0:00

drawing, paper

#

drawing

#

water colours

#

baroque

#

landscape

#

paper

#

history-painting

Dimensions: 470 mm (None) (billedmaal)

Filippo Luzi sketched this design for a silver plate, one of the so-called "piatti di S. Giovanni," depicting Cosimo III fortifying the port of Livorno. Dominating the composition is Cosimo himself, pointing towards the harbor, while a figure presents him with architectural plans. The gesture of pointing, a symbol of direction and authority, echoes through history, from ancient Roman emperors commanding legions to Renaissance patrons guiding artistic endeavors. This act of pointing isn't just about physical direction; it’s about imposing one's will upon the world, a primal assertion of control. Observe how the figures surrounding Cosimo look to him, seeking guidance and approval. This dynamic touches upon the very core of human interaction, the subconscious desire for leadership and order. The image resonates because it speaks to our ingrained need for authority, tapping into our collective memory of leaders and followers. It embodies the cyclical return of archetypes, reinventing ancient motifs in a modern guise.

Comments

statensmuseumforkunst about 2 years ago

⋮

This large and impressive drawing, hitherto attributed to Hinrich Krock, is a study by Filippo Luzi for one of the so-called piatti di S. Giovanni; silver plates which the Pallavicini family and their heirs presented to the Grand Dukes of Tuscany every year from 1680 to 1737 on the feast of St John (24 June), in accordance with the will of Cardinal Lazzaro Pallavicini. The plates were melted down around 1800, during the French invasion, but they are recorded in plaster casts in the Museo degli Argenti, Florence. They were made by different silversmiths from drawings by various painters. As Jennifer Montagu has demonstrated, the longest partnership was between the silversmith Ludovico Barchi and the painter Filippo Luzi, to whom this drawing can be attributed.[1] Luzi succeeded his teacher and friend Lazzaro Baldi, who was paid for the designs from 1698 to 1702. When Baldi died in April 1703 at the age of 79, he had probably already left the designs of the silver plates to his most talented pupil Filippo Luzi, who along with Giovanni Battista Lenardi was the executor of Baldi’s will. All the plates depict subjects from the history of the Medici family. Before 1700 they were historical, but after 1700 they were contemporary. It is not known who decided on the subjects each time. The Copenhagen drawing is a study for the 25th silver plate of 1704 that was presented to Grand Duke Cosimo III to commemorate his fortification of the harbour of Leghorn, as recorded in the inscription on the plate. When it entered the Medici Guardaroba on 26 June 1704 it was described as: “Bacino d’arg.to largo di diametro B.a 1 1/5 tutto lavorato di Cesello di basso rilievo entrovi il ritratto del Ser.mo Gran Duca Cosimo terzo regnéante vestito d’abito reale in atto di osservare una Pianta di fortificazione sostenuta da due figure simili una delle quali tiene la corona, con più soldati a cavallo armati, et in lontananza si vede il porto di Livorno e sue fortificazioni con fascia attorno del istesso lavoro di trofei militari, et inscrizione che dice Cosmus III M.D.AETR.Apliatijs perfettisque Liburni Anno 1704”.[2] The composition is actually very close to that of the 1703 plate with the enlargement of the church of San Cresci in Mugello. It is the first plate that Luzi designed after the death of his teacher Baldi, and the fourth known drawing by Luzi for this series, the others being those for the 1709 in the Uffizi,[3] 1711 formerly in the collection of Roberto Franchi, Bologna,[4] now belonging to Nicolas Schwed, Peris, and 1717 in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.[5] The four drawings are a fine confirmation of Nicola Pio’s statement in his biography of Luzi: “Nel disgnare è stato fertile, come nel comporre facile, grazioso et erodito, vedendosi apunto quella facilità nellli disegni da lui fatti per molti anni alla casa Rospigliosi, per il gran bacile istoriato che si faceva per il gran duca di Firenze, in sodisfatione del legato lassotogli dalla ch. mem. del card. Lazzaro Pallavicino”. [6] 1 Incrementsprotokol II, 1846-1869, p. 174; ms. in the KKS archive. 1 Montagu 1996, pp. 92-116. 2 Aschengren Piacenti 1976, p. 203, calco n. 10: 25. 3 Florence, Uffizi, GDS, inv. no. 5801 S (Fischer Pace 1997, p. 38, no. 16, ill.). 4 Tumidei ed. 1997, p. 150, no. 72, ill. 5 Philadelphia, Museum of Art, inv. no. 1984-56-586 (Percey and Cazort 2004, no. 28, ill.). 6 Pio 1977, p. 39. ASCHGREN PIACENTI 1976 Kirsten Aschengren Piacenti, "I piatti in argento di San Gio- vanni", Kunst des Barock in der Toskana Studien zur Kunst unter den letzten Medici, Italienische Forschungen heraus- gegeben vom kunsthistorischen Institut in Florenz, dritte Folge Band IX, Munich 1976 MONTAGU 1996 Jennifer Montagu, Gold, Silver & Bronze. Metal Sculpture of the Roman Baroque, New Haven and London 1996

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.