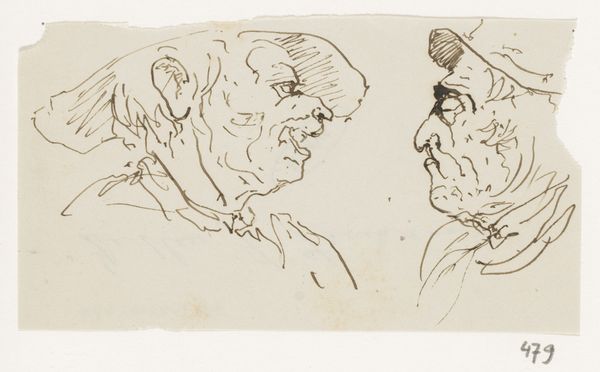

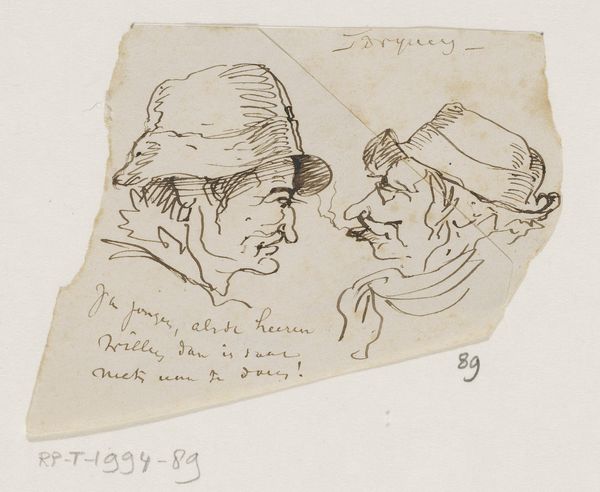

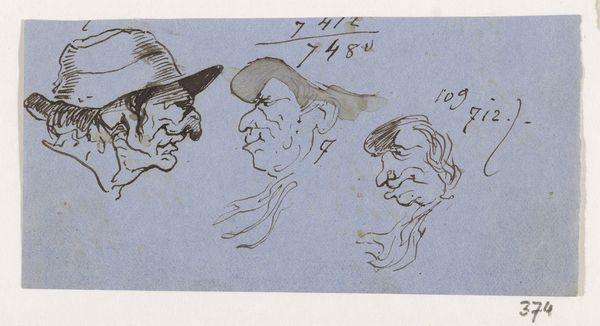

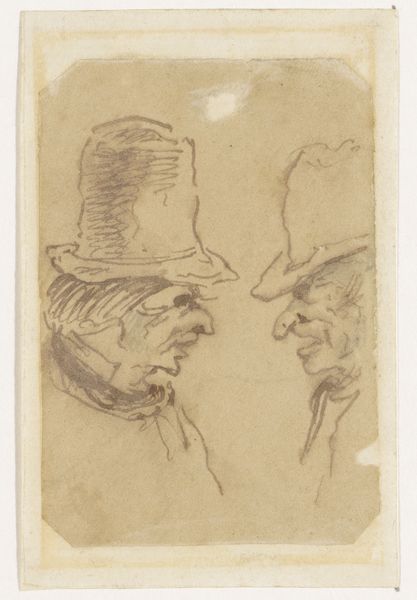

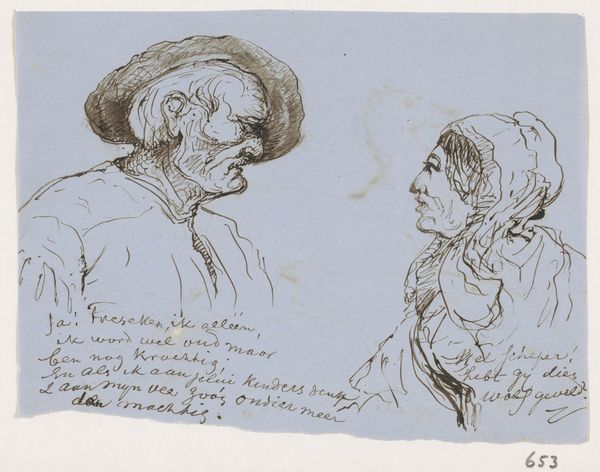

drawing, pen

#

portrait

#

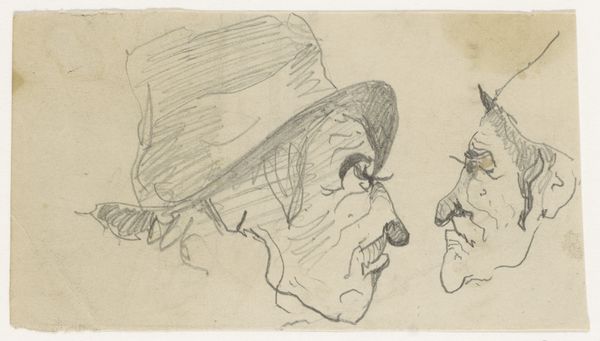

drawing

#

imaginative character sketch

#

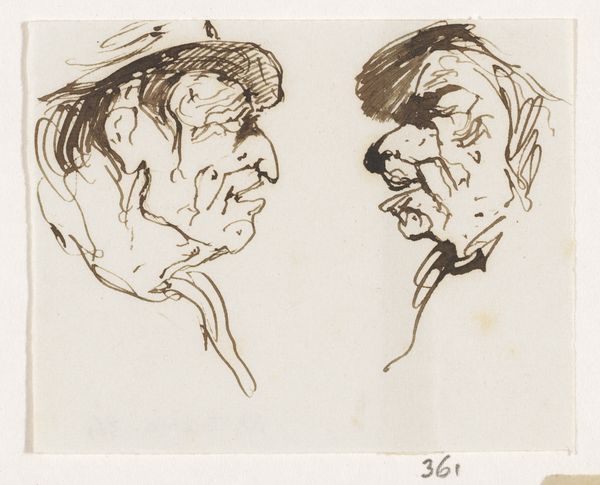

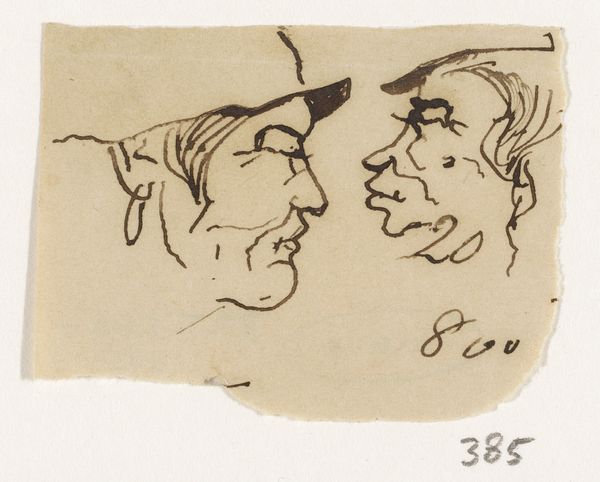

caricature

#

cartoon sketch

#

personal sketchbook

#

idea generation sketch

#

sketchwork

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

romanticism

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pen

#

watercolour illustration

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

sketchbook art

Dimensions: height 68 mm, width 119 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: We're standing before Johannes Tavenraat's "Three Caricatural Male Heads," dating from 1819 to 1881. It’s currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. It appears to be executed with pen. Editor: My first thought? Exaggeration! The artist certainly wasn’t shy about amplifying distinctive facial features here. It's got that sketch-book immediacy, like a glimpse into the artist’s imagination. Curator: Indeed. Caricature thrived as a visual shorthand in the 19th century. What makes this significant, in a historical context, is the way such imagery participated in, and sometimes challenged, social and political discourse. Cheap printed versions of such caricatures circulated widely. Editor: The heavy brow ridge in these faces gives me almost neanderthal vibes—the artist is making a statement. It's not just about physical features, but perhaps social commentary of that time. Curator: Precisely. There's a certain social leveling going on here. Consider the time frame; Tavenraat was working in the shadow of the Enlightenment and the French Revolution. Caricature became a potent tool for critiquing power and the established order. We must consider what specific message it may be delivering. What kind of men were people thinking about in these derogatory ways? Editor: I’m also struck by the artist’s line work. Look at the use of line and shading to describe the sunken cheeks, pursed lips and nose details; they become grotesque! It plays on visual archetypes and the idea of types, reinforcing certain cultural associations about those being drawn. Curator: The romanticist art period was well in motion during his time, even though it is caricature we cannot avoid his exposure to its concepts and application to social matters. Artists were starting to have very differing opinions about how artwork needed to appear to the world, or if artwork even should appear to the world at all. Perhaps this set of drawings were never designed to make the art world, perhaps these were never for anyone except him. Editor: It truly gives a feeling that you are inside of the artist’s private workspace and that no one was ever intended to see the work. Curator: This has helped me think of Tavenraat in a more nuanced context. It emphasizes the relationship between public and private art making and the political potential, of even what appears to be simple sketchwork. Editor: For me, I think about how potent the visual language of caricature continues to be. Exaggeration will always carry immense power, emotionally, culturally, even psychologically.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.