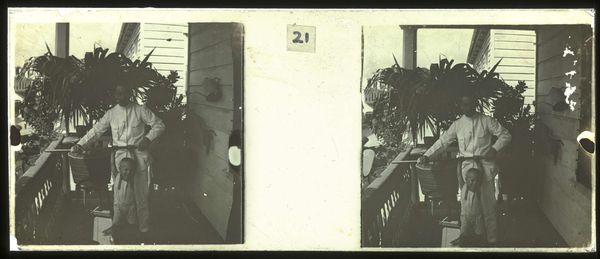

photography

#

portrait

#

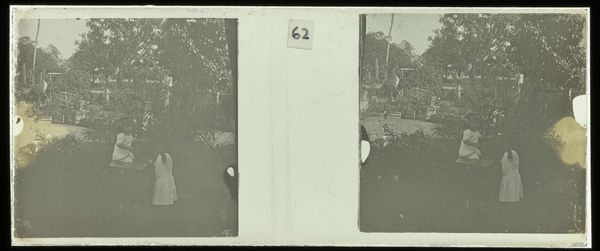

street-photography

#

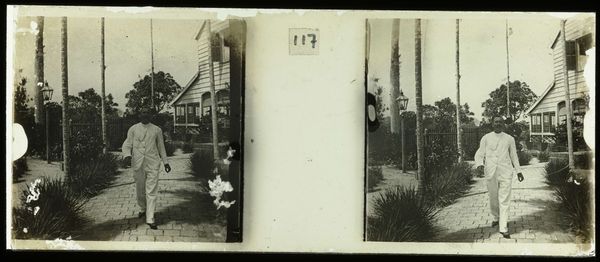

photography

#

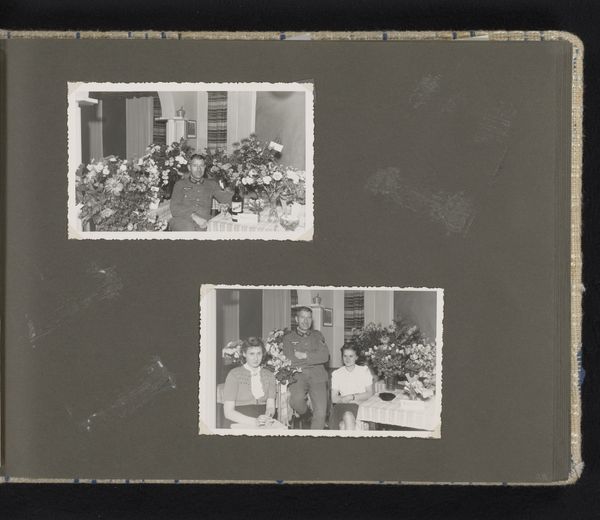

group-portraits

#

mixed media

Dimensions: height 4.5 cm, width 10.5 cm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is "Familie Brouwers in Suriname," taken sometime between 1913 and 1930 by Theodoor Brouwers. It's a photograph of a group of people. The composition feels very posed, yet there’s also an air of informality. What's your take on this piece? Curator: This image, framed within the visual culture of its time, offers a window into the complex colonial relationship between the Netherlands and Suriname. Group portraits like this often served as visual declarations of power and social standing, reflecting the colonial hierarchy. The setting—outdoors, but likely still on private land—further emphasizes that dynamic. Considering its photographic form, how might this work engage the history of photography within colonial regimes? Editor: It's interesting to think about it as a "declaration of power." I hadn't considered the ways the medium itself could contribute to the social message. I guess I'm wondering what the political context might have been like for photography in Suriname at the time? Curator: Photography in colonial contexts became a tool for documentation, classification, and control. It was a technology largely wielded by colonizers to capture images of the colonized, reinforcing notions of "otherness" and often solidifying racial and cultural stereotypes. However, understanding how local populations like the Brouwers might have co-opted photography for self-representation challenges the sole idea of colonial oppression. How do you perceive that tension here? Editor: That gives me a new way to consider photography's role beyond art. Thanks! This image sparked an unexpected discussion of colonial representation. Curator: Indeed. It invites us to question the power dynamics inherent in visual representation, and how seemingly simple photographs are woven into broader narratives of colonial history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.