drawing, print, woodcut, engraving

#

drawing

#

pen drawing

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

woodcut

#

line

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

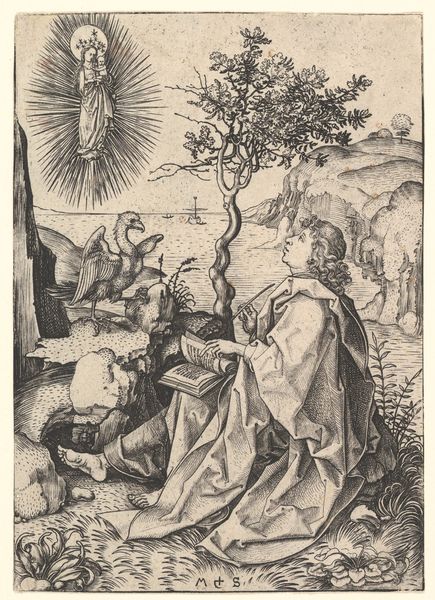

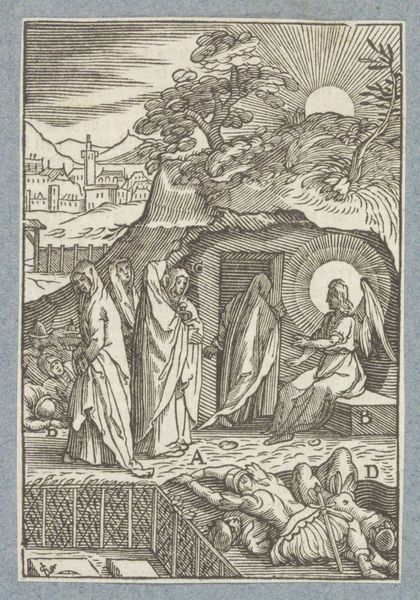

Curator: Here we have Leonhard Beck's "Saint Ramaricus," a woodcut or engraving created sometime between 1516 and 1518. Editor: My first impression is of a figure steeped in contemplation, dwarfed, almost overwhelmed, by the meticulously rendered wilderness surrounding him. The textures are incredible! Curator: Indeed. Beck uses line masterfully. Note the delicate hatching that defines the textures of the forest and the subtle modeling of the Saint's garments. He evokes a sense of Northern European spirituality. The light emanating from the halo symbolizes divine grace, yet it is intimately interwoven with nature. The artist emphasizes nature. What do you make of that, as an interpreter of material culture? Editor: The prominence of the landscape, created by carving away the wood, speaks to me of a specific time. It acknowledges a changing world, where the natural world begins to have as much importance as the saint. The artist likely sourced his wood locally, perhaps even from the same forests depicted here. Curator: Precisely. And Ramaricus himself becomes part of that landscape. Even the inclusion of his coat-of-arms reflects the lineage and local ties. Editor: That makes me wonder about patronage; someone commissioned this print and would be attuned to those particular visual queues and indicators. It shows me art always serves particular patrons with individual preferences. Curator: Note, also, the presence of the dragon in the underbrush— a common symbol for evil that the Saint might overcome through spiritual devotion, or possibly even an allegory of the wildness and challenges that this particular territory represents, in that patron’s history. It creates a tension with the background and halo, contrasting light and darkness. Editor: I'm fascinated by the sheer labor that went into crafting these intricate details by hand, and think of how they would be viewed in context. There must have been some awareness and value placed upon the human time spent on a material process. The consumption of an image then would take place much differently than it would now. Curator: Absolutely. These prints would have held significance, both spiritual and perhaps even political within the social fabric of the early 16th century. Editor: Understanding how these images are made lets me feel how that consumption or exchange happened. Curator: So much about this woodcut reflects a moment of change and growth. Thank you. Editor: Yes, a great reflection on making in history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.