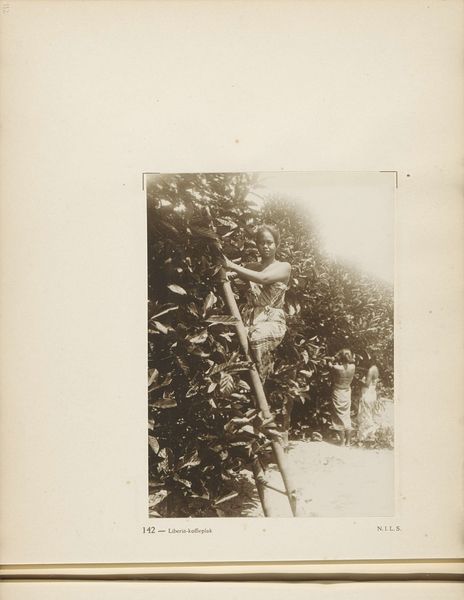

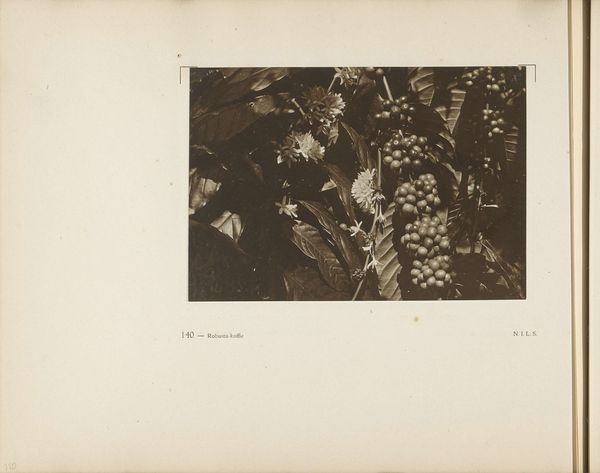

Pagina 158 van fotoboek van de Algemeene Vereeniging van Rubberplanters ter Oostkust van Sumatra (A.V.R.O.S.) c. 1924 - 1925

0:00

0:00

jwmeyster

Rijksmuseum

print, photography

# print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

orientalism

#

realism

Dimensions: height 240 mm, width 310 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this sepia-toned print, I'm immediately struck by the density of the vegetation and the lone figure almost swallowed within it. It feels... isolated, doesn't it? Editor: Indeed. What we're viewing is page 158 from a photo book documenting the Algemeene Vereeniging van Rubberplanters ter Oostkust van Sumatra, or AVROS. The photographer, J.W. Meyster, captured this scene circa 1924-1925. AVROS was a colonial association, primarily composed of European investors exploiting Sumatran resources. Curator: Knowing that historical context definitely shifts the reading. What I initially saw as picturesque now has this weight of exploitation and inequality attached to it. The worker's submersion within the plants reads less as natural harmony, and more as forced labor obscured from view, their individual identity becoming almost indistinguishable from the landscape. Editor: Precisely. Images like this served a dual purpose. On one hand, to document the productivity of the plantations, offering reassuring visuals of their investments back in Europe. But they also subtly reinforced colonial power structures. Consider the perspective – the photographer has framed the worker within the rows of crops, implying order and control of both labor and landscape. Curator: And even the so-called realism is constructed. Photography can often create the illusion of an unmediated window to reality, but images such as these were deeply mediated representations that helped solidify social and cultural beliefs of the period. In orientalist discourse, Asian laborers were routinely represented as docile, faceless parts in the larger economic machine of their colonizers. Is this photographic documentation complicit in that narrative? Editor: The absence of a unique or identifiable identity does, consciously or otherwise, dehumanize. Think of it also in terms of its broader circulation in the colonial system of its time: the book’s intended European readership likely saw something entirely different from a modern audience viewing this now within the Rijksmuseum. What lessons do these shifts of perspective over time carry? Curator: The image then functions as a mirror reflecting not only a specific historical moment, but the shifting power dynamics that continue to shape how we perceive and interpret visual cultures of the past. It's a powerful, albeit troubling, lens. Editor: Agreed. It invites a necessary discomfort, reminding us that even seemingly objective records like photography can be laden with ideological frameworks, their afterlives always open to reassessment.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.