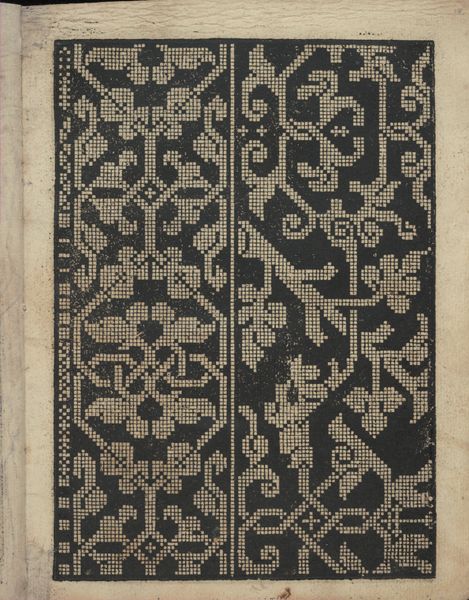

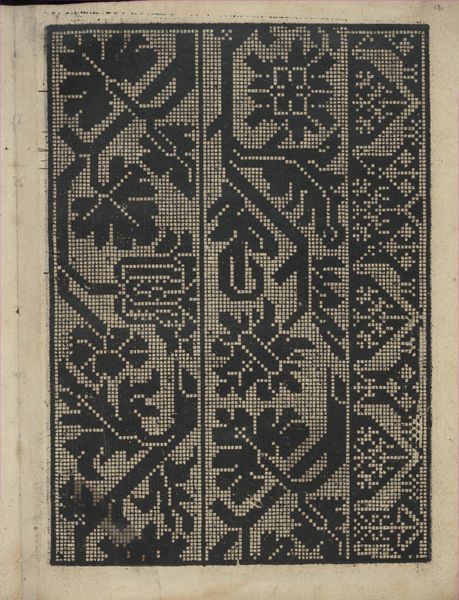

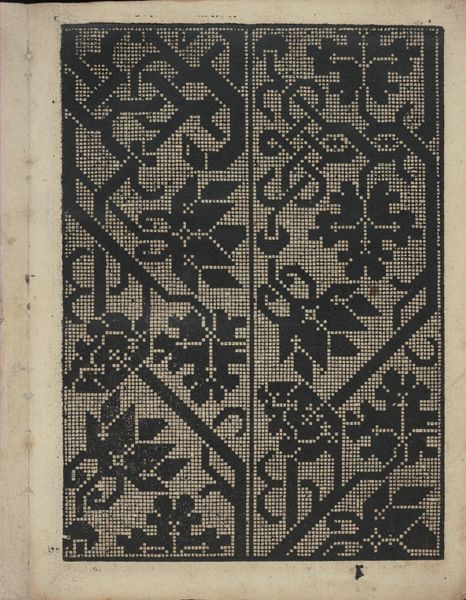

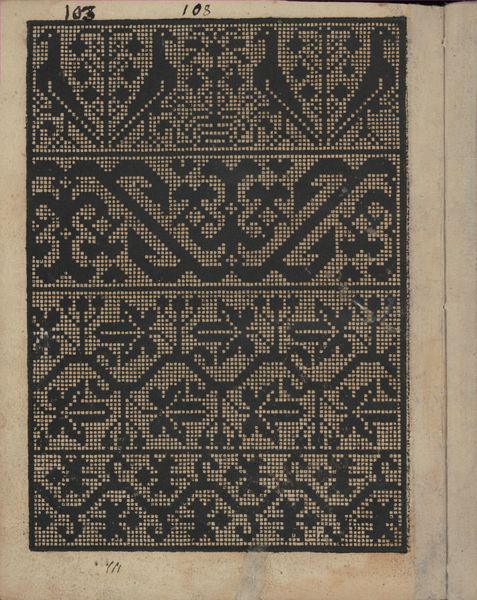

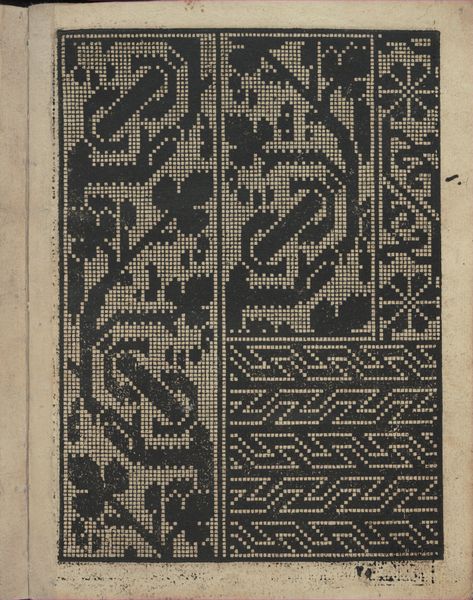

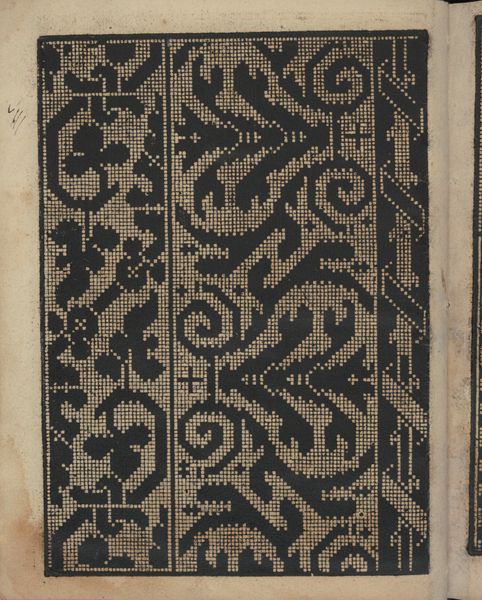

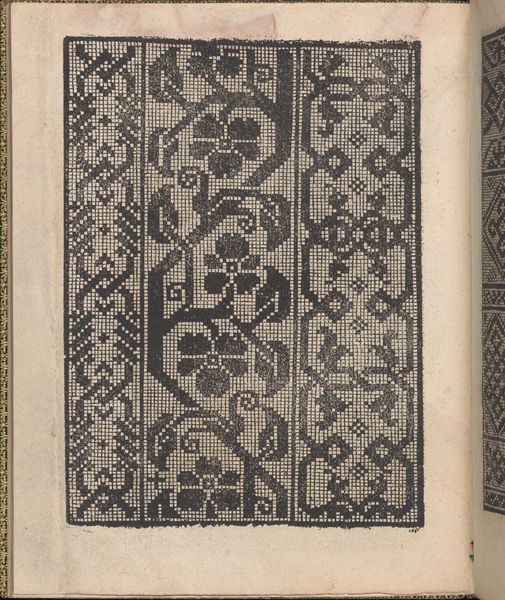

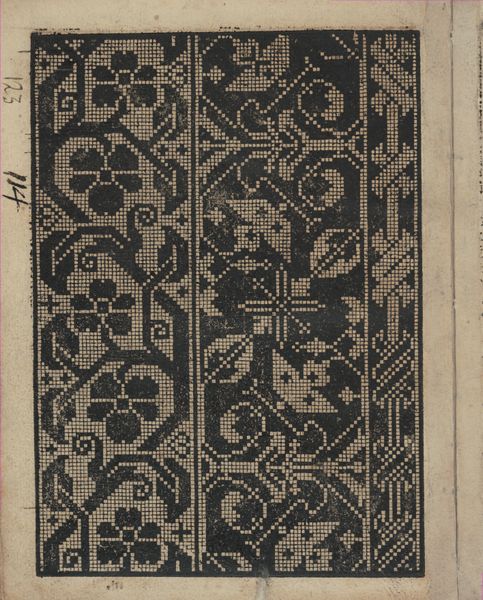

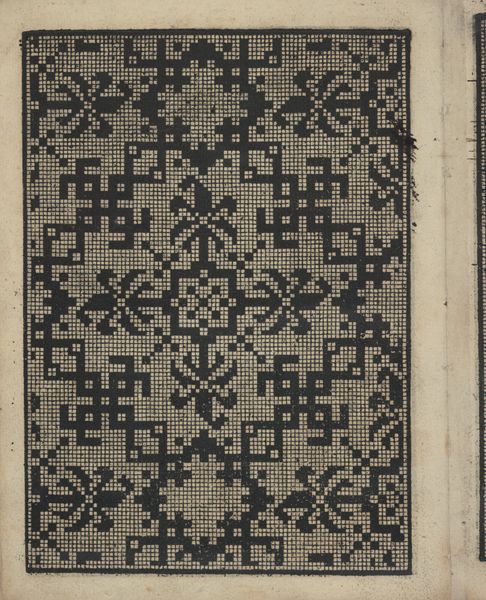

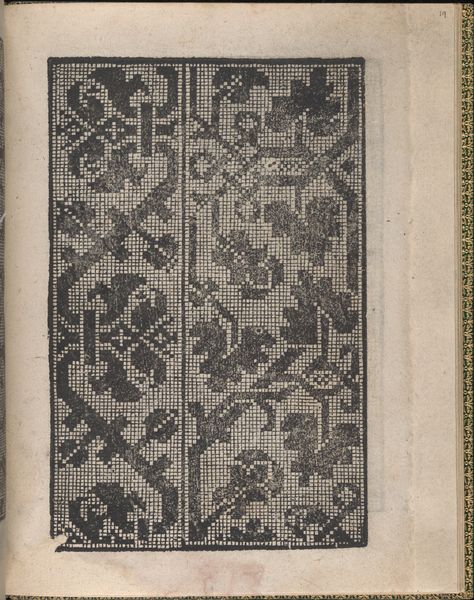

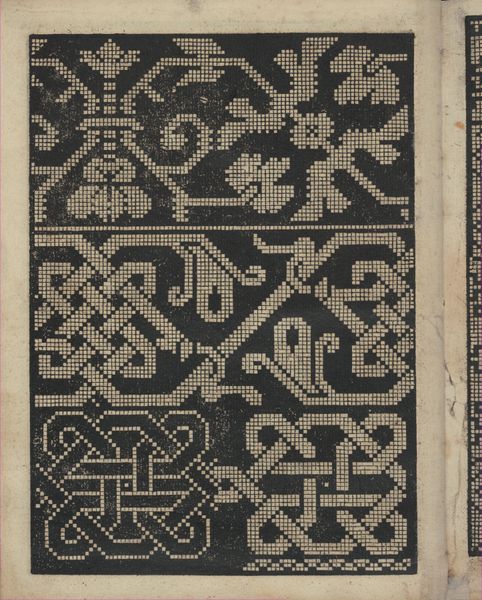

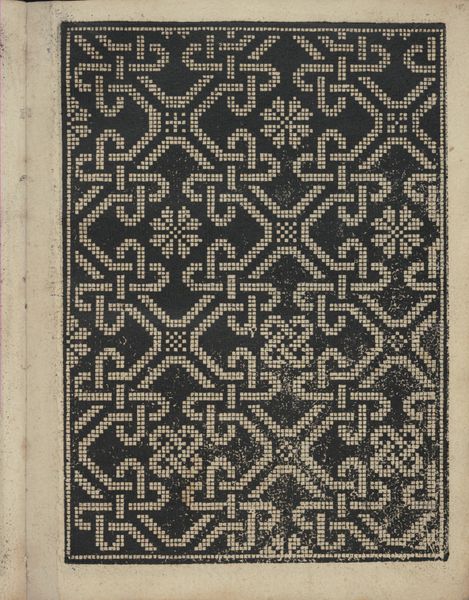

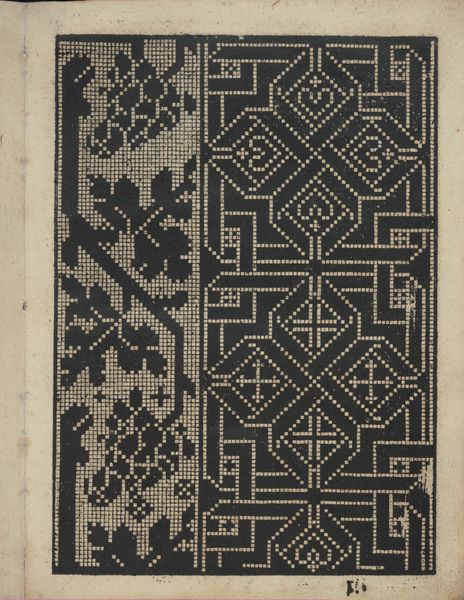

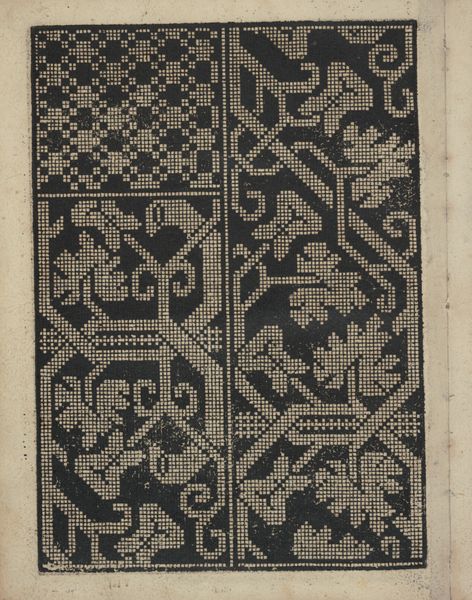

Libbretto nouellamete composto per maestro Domenico da Sera...lauorare di ogni sorte di punti, page 6 (verso) 1532

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, textile

#

drawing

# print

#

book

#

pattern

#

textile

#

decorative-art

#

italian-renaissance

Dimensions: Overall: 8 1/16 x 6 5/16 in. (20.5 x 16 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This striking image is from a book published in 1532, "Libbretto nouellamete composto per maestro Domenico da Sera…lauorare di ogni sorte di punti", attributed to Domenico da Sera. This particular page features designs for needlework patterns, rendered in print. Editor: The contrast is what grabs me immediately. The graphic interplay of the dark background and the almost pixelated lighter motifs gives it an unexpected, contemporary feel despite its age. Curator: It's important to remember the context. These pattern books were essential in disseminating designs during the Renaissance, influencing not just textiles but also broader notions of adornment and status. Needlework was primarily the domain of women, offering a form of creative expression—and sometimes, economic agency—within prescribed societal roles. Editor: So the repeating floral and geometric shapes are, in essence, coded language. I wonder what meanings these individual symbols might have carried? Are there echoes of earlier pagan motifs woven in, or are these strictly Christian symbols, repurposed in a domestic craft? Curator: It’s likely a mix. Renaissance patterns often drew upon classical and natural forms, subtly infusing them with contemporary religious and moral values. The act of creation itself – the time-consuming process of stitching – became a virtue. It symbolized patience, piety, and domestic skill, qualities highly valued in women of the era. The visual harmony can also symbolize larger cosmic ideas, reflecting the human desire to bring order and beauty to their world. Editor: You're making me consider the politics embedded within something seemingly so benign as a needlework pattern. The restriction to the domestic sphere contrasts sharply with the expansion of the Renaissance, with colonial aspirations extending globally, fueled in part by similar aesthetic desires for conquest. Curator: Precisely. The production of these intricate designs became inextricably linked to the socio-political landscape of the 16th century, reflecting the hierarchies and values embedded within the elite circles that commissioned and consumed them. Editor: This makes me think about craftivism today: contemporary textile artists are still using threads to confront, provoke, and negotiate for recognition, but now, instead of encoding symbolic imagery into pattern for private use, their designs are laid bare and presented boldly within the public domain. Curator: Thank you; I’m finding it interesting to rethink how to value something like this, from a seemingly functional embroidery pattern of the Italian Renaissance into the intersectional perspectives around artistic expression, class, and gender roles of both that era and our own. Editor: This look has offered a fascinating portal to the multiple layers within what might otherwise be taken at face value as simply an appealing example of domestic design, hasn't it?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.