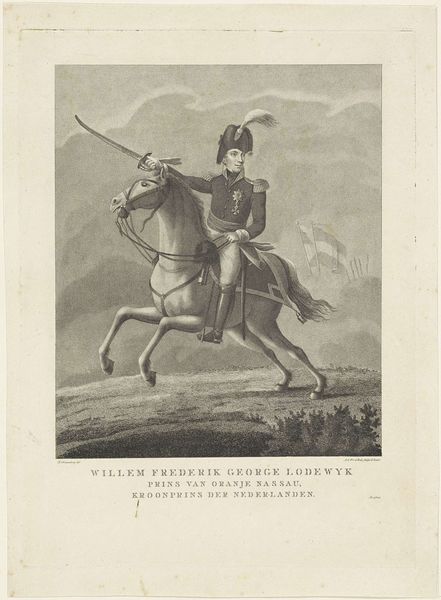

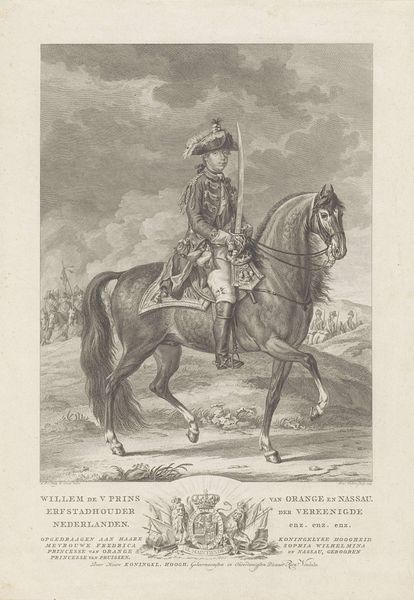

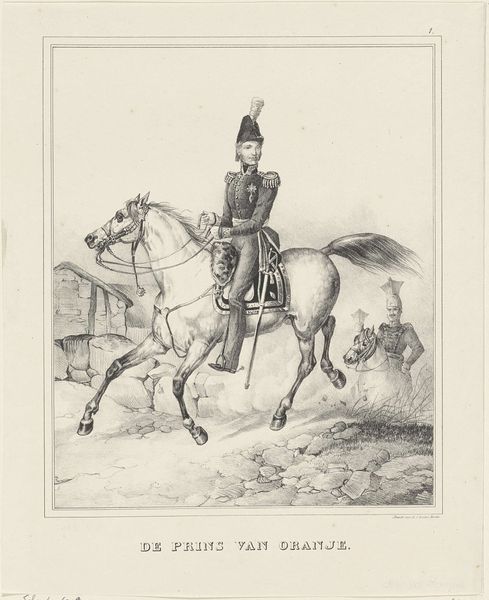

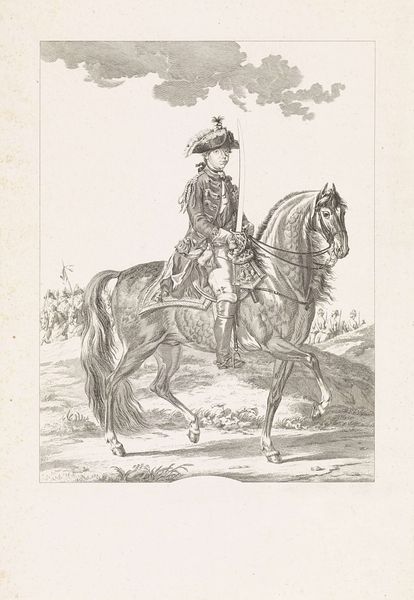

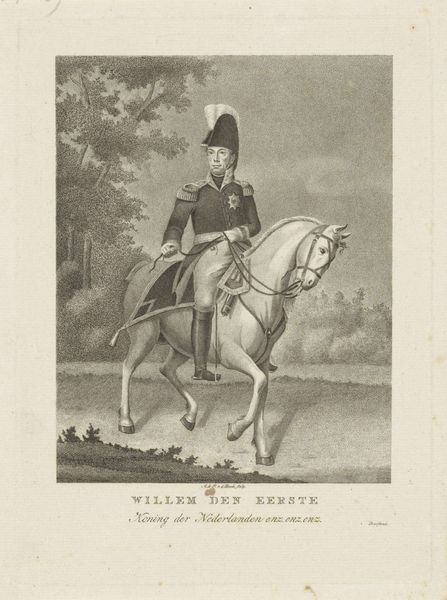

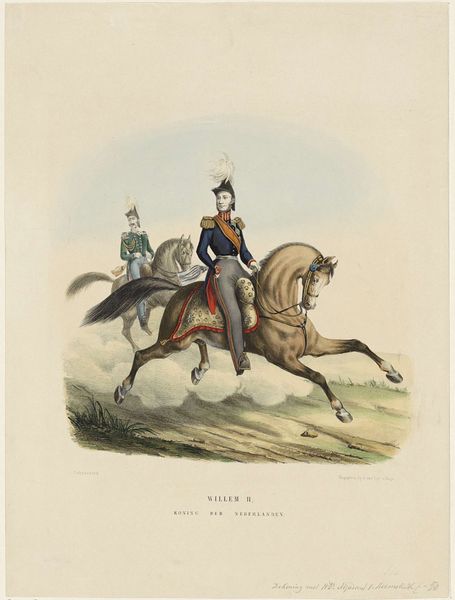

Ruiterportret van Willem I Frederik, koning der Nederlanden 1815 - 1821

0:00

0:00

antonieenpietervanderbeek

Rijksmuseum

#

pencil drawn

#

photo of handprinted image

#

aged paper

#

light pencil work

#

photo restoration

#

pencil sketch

#

old engraving style

#

archive photography

#

historical photography

#

pencil work

Dimensions: height 395 mm, width 292 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have the "Equestrian Portrait of William I Frederick, King of the Netherlands," created sometime between 1815 and 1821 by Antonie and Pieter van der Beek. It has this rather regal and composed mood; almost like a painting of power, if that makes sense. How do you interpret this work? Curator: Indeed. Consider the era – post-Napoleonic Europe. Images like this, depicting rulers on horseback, were deliberate tools of nation-building. They reinforce the patriarchal narrative of leadership, connecting it to military might and a legacy of power. What message do you think it conveys to a society recovering from upheaval? Editor: It seems pretty straightforward - "We are in charge now." But I wonder about the artists. Were they just following commission or do you think they actually agreed with this message? Curator: Exactly! Now, think about the role of artists in such power dynamics. Were they merely chroniclers or active participants in constructing these narratives? The subtle idealization of William’s figure, the imposing but slightly generic landscape… all contribute to the overall effect of legitimizing his reign, perhaps obscuring the complexities of a nation still in formation. Consider also, who might be excluded from this narrative? Editor: The working classes, maybe? People without a say? Curator: Precisely! This image doesn't just show power; it actively participates in defining who *has* power and, implicitly, who does not. Visual representation becomes a form of social control. So, thinking about art history not just as a sequence of beautiful images, but a set of constructed narratives... how does that shift your perspective? Editor: It's less about face value. And more about who gets to tell the stories... Curator: Yes. It encourages a critical approach, questioning the motives and societal structures behind artistic creation. Power is never just "shown"; it's performed, negotiated, and constantly redefined, particularly through imagery. Editor: This makes you see artwork completely different, there's always some historical context. It seems there is a power struggle in every image and message behind what is painted.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.